Inundation District

Season 8 Episode 14 | 1h 18m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

Examining the short-sighted political decisions of one American city in an era of rising seas.

In a time of rising seas, one city spent billions of dollars erecting a new waterfront district - on landfill, at sea level. Unlike other places imperiled by climate change, this community with some of the world’s largest companies was built well after scientists began warning of the threats. The city called its new neighborhood the Innovation District. Others are calling it INUNDATION DISTRICT.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Wyncote Foundation.

Inundation District

Season 8 Episode 14 | 1h 18m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

In a time of rising seas, one city spent billions of dollars erecting a new waterfront district - on landfill, at sea level. Unlike other places imperiled by climate change, this community with some of the world’s largest companies was built well after scientists began warning of the threats. The city called its new neighborhood the Innovation District. Others are calling it INUNDATION DISTRICT.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Local, USA

Local, USA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipALLEN MCGONAGILL: The State of Massachusetts has invested $20 billion in the Seaport District.

TINA MCDUFFIE: In Boston's Innovation District, development is rapidly expanding.

But now rising sea levels and flooding threaten to turn the Innovation District into an inundation district.

STEVE HOLLINGER: The city has been negligent.

ANTÓNIO GUTERRES: We are still careening towards climate catastrophe.

MCDUFFIE: "Inundation District," on "Local, U.S.A." ♪ ♪ (crowd applauds softly) WOMAN (chanting): News alert, it's getting hotter!

PROTESTERS: Boston will be underwater!

WOMAN: News alert, it's getting hotter!

PROTESTERS: Boston will be underwater!

WOMAN: News alert, it's getting hotter!

PROTESTERS: Boston will be underwater!

(cheering and applauding) MCGONAGILL: Today, we're going to be going into the Seaport District of Boston.

And it doesn't take a genius to look at that, at sea level, and tell that we shouldn't be building buildings there with climate change on the way.

The State of Massachusetts has invested $20 billion in the Seaport District.

In the next ten years, if a nor'easter hit the Seaport District, it would cause over $1 billion of damage.

And who do you think is gonna pay for that damage?

WOMAN: We are!

- We are.

Today, we will shatter that climate silence, and every single person in the Seaport District is going to hear us.

♪ ♪ DEANNA MORAN: The Seaport is unique because it didn't exist-- at one point, it was water.

It's also an interesting case because it's a brand-new neighborhood.

LOUIS ELISA: The changes that have taken place and the permissions that have been given for people to build in the coastal zone and around the water's edge without taking in consideration the long-term impacts is of real concern to me.

We had developers come in, build buildings, and then get out five years later.

There was no attention paid to sea level rise.

Absolutely none.

This place is gonna be subject to devastation.

And the building continues.

♪ ♪ ROB DECONTO: So, as we keep increasing the carbon dioxide concentrations of the atmosphere, we're worried that we could be approaching some tipping points in the climate system that could trigger some really pretty extreme events.

If sea level comes from a big loss of the Antarctic ice sheet, Boston will feel 25% more sea level rise than the global average.

Boston is one of the most vulnerable cities on the planet to sea level rise and to flooding.

80 years from now, a lot of the Seaport is just going to be underwater not just during high tides or extreme high tides or during storms, but all the time.

(people talking in background) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ And we plan to own this area for a very long time.

It's important to us to design for the future.

YANNI TSIPIS: And so it's a terrific responsibility for us to make sure that we're thinking about not only our generation, but future generations, and that we're thinking about the future of the city.

♪ ♪ (camera shutter clicks) RICH MCGUINNESS: Coastal flooding, sea level rise, really wasn't on anyone's radar.

The city wanted to unlock its potential.

"We need housing, we need jobs."

And the framers of the city saw an opportunity.

CARL SPECTOR: It's too complex to say whether or not it was a mistake to build the Seaport as we did.

If we knew everything that we know now a dozen years ago, we could have been asking more.

AMY LONGSWORTH: So now the Seaport area is bustling.

Major companies are based there.

At some point, the Seaport will no longer be viable.

The sea level will be too high, unless they want to literally wall themselves in.

If we can't get ourselves together to prevent six, seven feet of sea level rise, I'm not sure that we're a society that deserves to survive.

PROTESTERS: ...power of the people 'cause the power of the people don't stop.

MAN: Say what?

PROTESTERS: There ain't no power like the power of people 'cause the power of people don't stop!

MAN: Innovation District?

There's no chance that innovation is going to outlast inundation in the Seaport.

This is going underwater.

This is the Inundation District.

(siren blaring in distance) WOMAN: The secretary general of the United Nations, António Guterres.

(audience applauding) GUTERRES: The six years since the Paris Climate Agreement have been the six hottest years on record.

Our addiction to fossil fuels is pushing humanity to the brink.

We face a stark choice: either we stop it or it stops us, and it's time to say, "Enough."

We are digging our own graves.

Our planet is changing before our eyes, from the ocean depths to mountaintops, from melting glaciers to relentless extreme weather events.

Sea level rise is double the rate it was 30 years ago.

Oceans are hotter than ever, and getting warmer faster.

We are still careening towards climate catastrophe.

Failure is not an option.

Failure is a death sentence.

We face a moment of truth.

We are fast approaching tipping points that will trigger escalating feedback loops of global heating.

Over the last decade, nearly four billion people suffered climate-related disasters.

That devastation will only grow.

Excellencies, the sirens are sounding.

Our planet is talking to us and telling us something.

We must listen and we must act.

(birds chirping) NATHAN WYATT: A couple of years ago, this wasn't really happening.

Um, you know, it'd come through the boards.

People talk about it flooding.

It happens, like, every couple years.

It's happened probably, like, three or four times in the last year I've been out here.

♪ ♪ Now we're having warnings about the, the high tide, you know, every time it, you know, rains, or there's a storm coming through, it'll get pretty high and come through.

♪ ♪ It's a nice spot, good view.

I mean, this is a spot where, like, you know, people take pictures and they sell the pictures for money.

This is a beautiful view down here.

It used to be just all construction and ships and stuff like that.

Now it looks like Little Manhattan in Boston.

It's crazy how much stuff came up.

I feel out of place walking over there.

I don't go over there, especially being homeless.

I just stay away from it.

If you think climate change isn't real, it's like you look at the color blue, and it's not blue.

It's the stupidest thing in the world.

It, look at the numbers, look at what's happened around the world.

I mean, it's...

It's so easy to notice climate change.

It's changing things on a ridiculous pace.

And if we started fixing things 40 years ago, we still would've been too late.

It doesn't matter what we do, it's gonna happen.

It's affecting everyone.

If you're in a part of the world where it's only affecting you a little bit, even that little bit, you notice it's everywhere.

The people who don't think climate change is real is kind of like-- it gets me riled up, like talking to a flat-earther or something like that.

(chuckling) When you hear the slapping sound over there, that's when... That'll get me moving.

Then you know it's gonna come up, it'll start spraying through the cracks.

(water slaps wall) It'll be from, like, one inches to a foot above the dock, which is sad, because they made it high enough where they thought this would never happen.

(water slaps) I've been on the dock where it's flooded, and had a tarp down, and been so asleep that I didn't know, and get up, and it's spraying everywhere.

(laughs) Sometimes I'll be asleep and I'll get wet.

Especially at this time of year, you don't want to be wet.

(water slapping wall) The people that are alive now are alive and well, but they don't understand their children are gonna suffer from it.

This is a great (indistinct) next to the water.

It's like that polar bear that gets stuck on that small piece of ice, and he can't get to land and he can't eat.

Look at this-- this wouldn't come up this... Five years ago, it would be at least another foot and a half down for the highest.

♪ ♪ You can live in your eggshell and not worry about it, but things are pressing so fast, I think in a couple of years from now, people will really wake up, 'cause they'll see a lot more things happen around them.

I put my stuff way over there, it stays dry.

I find if I leave it down here, it'll get wet.

It's a good thing I'm still young, I can put it somewhere I can get it.

I don't usually have this much stuff.

I didn't know the water was gonna be this high this morning.

But I feel terrible for my nephews and nieces.

They're gonna grow up and be here on this planet 30 years after I am, or 40 years after I am, and see what's gonna happen to the planet.

That's terrifying to me.

♪ ♪ REBECCA SHOER: So, if you're here for the first time, this is not what Long Wharf usually looks like.

It is not usually underwater.

It's usually a nice place to come get pictures, eat your lunch, things like that.

So, today, we have a prediction of about 12.1 feet for the high tide.

That's about two feet higher than normal.

That's higher than what it was yesterday, and it was starting to top my boot.

So even though this is a natural, predictable phenomenon, this has really big implications for sea level rise.

This is actually a really nice preview of what sea level rise might mean for Boston in the next 50 to 100 years.

So we think about, this might be every high tide, depending on how high the ocean rises.

ALICE BROWN: What we're experiencing is what some locals call a wicked high tide.

Other people call it a king tide.

All of which means that the Earth, the sun, and the moon are all in line.

So this is a totally naturally occurring phenomenon.

But it is higher today than it would've been 30, 40 years ago.

Regular high tides are gonna get higher and higher and higher.

It's going to do damage.

RACHEL VINCENT: As the sea level is rising with the changing climate, this could be what every high tide looks like in Boston, and that's just a really a wild wakeup call to realize, especially on historic structures like this.

♪ ♪ As you can see, part of the city is underwater right now.

These normal high tides will probably start to have a lot more of it underwater a lot more often at just normal, sunny-day high tides, let alone thinking of storm surges.

And you see on our signage here-- this isn't to scale-- but by 2030, we're expecting to see a foot of sea level rise.

The sea has already risen about eight inches in Boston Harbor.

By 2070, we expect to see about three feet, and by 2100, at least five feet of sea level rise.

So this is definitely gonna have some big implications for this coastal city.

This is not the only place that floods like this.

Right now, if you go down to the Seaport, you're gonna see this level of flooding.

The Seaport is a really high-risk area because it's so close to the water.

The ocean's coming.

This has huge implications for our livelihoods, our infrastructure.

And think about, right now, it's a beautiful, sunny day.

This is what we call sunny-day flooding.

But imagine if this was a week or two ago during our nor'easters: this water would be all the way down the wharf.

It would be getting into our T stops, it would be getting into our businesses.

Folks would have to put up floodgates.

So this is really important-- this is what reality might be.

How are we going to deal with climate change?

We know it's coming, and we have to think a lot more long-term than we used to.

So it's not just, what can we do in the next five, ten years, it's 50, it's 100, 200.

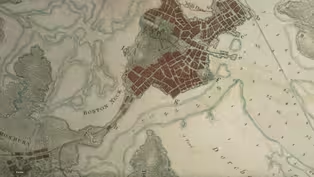

♪ ♪ NANCY SEASHOLES: I'd always been interested in how the land in Boston got made.

I actually used to work as an archaeologist.

My job was to do the research to figure out what had been there before we ever did any digging.

Eventually, I accumulated a lot of information about this.

Hello.

You all know that this part is totally artificial-- that didn't exist in the 1830s.

- Yes, yeah.

- Okay.

I'm Nancy Seasholes.

I'm the author of "Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston."

Boston almost certainly has more made land than any other city in North America.

This is Boston at the end of the revolution.

A little landmaking had been done around this original very small peninsula that was connected to the mainland only by this narrow neck.

This is essentially the original Boston peninsula.

Boston's solution for this need for more space and more land was to make it.

And they made it by filling in the tidal flats that surrounded the original areas, tidal flats being areas that are covered with water at high tide and exposed mud flats at low tide.

The way they made land in Boston was really simple.

They built a structure on the flats around the outer perimeter of an area to be filled, and then they just dumped in fill behind it, until the level of fill was above the level of high tide, and that's all it took.

They just collected whole cartloads of trash and dumped them in.

We find big collections of shoe leather, or wine bottle glass, or broken glasses from taverns, things like that.

Boston was famous for having a number of hills on it.

Most of those hills were cut down to use as fill.

It was relatively easy, it was available, and people didn't give it much thought.

What's now the Seaport District began as a harbor improvement to build the seawall around the South Boston flats.

The harbor commissioners thought that they were building a major port terminal with piers that would be served by railroads.

Actually, what happened was, they filled this whole area with great enthusiasm, and then it lay just basically empty for 100 years.

It was the last really big undeveloped part of Boston.

The problem was, they only filled it just above the level of high tide.

With sea levels rising, the level of high tide is a lot higher, and therefore, it's subject to flooding.

♪ ♪ (people calling and talking in distance) SEASHOLES: This is Faneuil Hall.

It's one of the most iconic buildings in Boston.

It's really considered one of the most important sites in revolutionary-era Boston.

This area, like most of the areas of Boston that is on made land, was only filled above the level of high tide at the time.

That's all they thought they needed to do.

So all of these areas of made land are subject to flooding with sea level rise.

This whole area was a big cove.

All of this area was originally tidal flats.

In other words, where Faneuil Hall is is all manmade land.

All of this was water.

BILL GOLDEN: A guy from Hull will tell you that in the last storm, it breached in 12 different locations.

Wasn't even a big storm-- wasn't even nor'easters.

It's not if, but when.

- Yeah.

Failure is not an option.

GOLDEN: My name is Bill Golden.

I am the project manager for a group called the Boston Harbor Regional Storm Surge Working Group.

Coastal flooding is an existential issue for the city of Boston.

This is no joke.

This is the existence of this area as an economic engine for New England and the, and the country.

It's a threat to the businesses in Boston.

It's a threat to the people that live here.

And it means that if we don't do the right thing, we're going to have to retreat from Boston.

This is real.

This is an existential threat.

A clear and present danger.

People say, "Ah, we're not gonna get flooded," and they, they say it's something way off in the future.

But the real urgency is, we have to act now.

We're playing Russian roulette with nature.

Make no mistake about that.

ELISA: As a planner, I can urge you and tell you that if you don't take these environmental issues into consideration, the cost is going to be tremendous.

We can see the water rising.

What we can't do is change the course of nature.

Water finds its own level, it will go where it has to go, and it'll go when it wants to go.

The only thing you can do is prepare for it.

JOHN MULVEYHILL: Flooding is gonna get worse before it gets better.

If we don't take the bull by the horns and start doing something about it, a lot of land is going to become part of the ocean.

I see it, I see it every time there's a storm.

We cringe every time there's an astronomical high tide and a nor'easter or, or a southeaster coming.

We're all vulnerable.

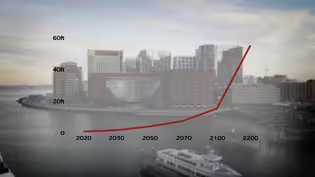

GOLDEN: We're facing two separate phenomenon, sea level rise and storm surge.

Now, you hear a lot about sea level rise.

You see these hockey stick projections.

Right now, it's very gradual.

Next 40, 50 years, it begins to increase significantly.

And if we lose the glacier or the ice cap, it goes up dramatically.

But the urgency of the situation is storm surge.

There's a 100% chance it could happen anytime.

And that when it does happen, it's devastating.

That is the most important thing to focus on here.

It's storm surge that really is the danger and destructive force.

So what we have proposed is something we call a layered defense: seawalls on land to protect against sea level rise and a sea gate system to protect against storm surge.

It would have large commercial gates to allow commercial shipping through.

(ship horn blaring) JACOB WYCOFF: In three, two... A recent study found the Boston Harbor Islands to be endangered, and the main cause of that is sea level rise.

Now, Golden tells me this sea gate system will not only protect those islands, but also the city of Boston, as well.

We know that the storms are out there.

And we know the sea level is rising, but it's like "Jaws."

It's out there, it's killed thousands of people, but today, the sun is shining, so we're going to keep building.

We're going to keep developing.

Who's responsible?

Is it going to be the builder that built it?

Or is it going to be the taxpayers?

Because if we end up building a 20-foot wall around the Seaport, it's the taxpayers that are going to pay to protect that area, and they're the ones that are gonna be left holding the bag for mistakes of the people that created the Seaport without consideration for sea level rise and storm surge.

VIDEO NARRATOR: Seaport is a vibrant 21st-century neighborhood.

Innovation, architecture, and modern amenities converge to create Boston's most sought-after destination.

The Seaport project by WS Development comprises over seven million square feet of mixed-use development, spanning 20 city blocks and anchored by over 1.1 million square feet of retail space.

(tools whirring and buzzing) (construction noises merge into music) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ MAN: Welcome to the opening celebration of The Rocks at Harbor Way.

Please welcome Yanni Tsipis to the stage.

(audience cheers and applauds) TSIPIS: Good afternoon, everyone.

Thank you all very much.

Our attention is drawn to changes in the skyline in this, Boston's newest neighborhood, and certainly, the pace of change here in recent years has been very rapid.

It's still very much a work in progress, even as we complete this new piece of Boston's future.

So it's fitting that we mark today by peering for a moment through the lens of history.

Now, Boston has been called many things over the years.

John Winthrop called it the City on a Hill.

It's been called the Athens of America.

Oliver Wendell Holmes referred to it as the Hub of the Universe.

Today, we celebrate not only the completion of a construction project, not only the Herculean labors of the skilled men and women of the Boston building trades.

Today, as we mark an important milestone in the city's future, we acknowledge the past and we embrace the creation of a true common ground.

It will also play a small but mighty role in helping to bring together our city and heal our planet.

All are welcome here.

Thank you all very, very much.

MAN: One, two, three... (playing mellow tune) (cheering) I oversee the Seaport development, which is a collection of 20 city blocks, 33 acres.

We are currently the largest private landowner and developer in the Seaport neighborhood.

And so it's a terrific responsibility for us to make sure that we're thinking about not only our generation, but future generations, and that we're thinking about the future of the city.

We're always trying to think ahead.

We're long-term owners, and so we try to think not just a year or two ahead, but a decade or two or three ahead when we build our-- both our buildings and our public open spaces.

These things are built to last for generations.

(people talking, music playing in background) PRANGE: It's an incredible opportunity for us and for our city, to create a new neighborhood in our city.

We are a long-term landowner, and we plan to own this area for a very long time.

It's important to us to design for the future.

(band playing) (thunder rumbling, rain pounding) (thunder claps) (rain continues) (wind whipping) ♪ ♪ REPORTER: Today in Boston, the high water returns, submerging parts of the Seaport.

REPORTER: Residents telling us it's unlike anything they had seen.

REPORTER: Crews are working to protect property from historic flooding.

REPORTER: We've had our three highest storm surge records set within the past century.

REPORTER: A lot of that storm surge expected to flood Boston's Seaport District.

REPORTER: This is what Boston's Seaport District looked like, icy water flooding down Congress Street.

REPORTER: It was a very rough day for the city of Boston.

And we could see a record high tide in Boston.

REPORTER: Now, some folks see this kind of storm fallout as the new reality.

This street is quickly and rapidly filling up with a lot of water.

And it's unreal-- I've never seen anything like this before.

REPORTER: Inches of water disguised by snow covered Boston's Atlantic Avenue, a slushy mess that poured into the Aquarium T station, shutting it down.

MAN: This is the second 100-year storm this year.

This is a new reality.

REPORTER: A storm surge is well underway, making it for a very messy day here in Boston.

REPORTER: The flooding was another reminder of Friday's historic nor'easter, cars and trucks submerged in water.

REPORTER: The first question we want to ask you about is the flooding all along the Seaport.

MARTY WALSH: When the high tide came in, you know, it really, it caught a lot of neighborhoods by surprise.

Things that we have to look out for in the future now as far as tide coming in.

REPORTER: It didn't take long for that storm surge to flood out parts of State Street, and Atlantic Avenue is now completely underwater.

This slush at my feet was two feet of water that came seeping in from Boston Harbor.

REPORTER: The story was much of the same in the areas closest to the ocean, water lapping into the streets.

Water has completely come down State Street here.

REPORTER: Floodwater sending this dumpster floating down an alley in the Seaport.

(siren blaring in distance) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ DECONTO: I'm Rob DeConto, I'm a professor at UMass Amherst.

I study ice sheets and sea level rise.

We're at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland.

We're trying to support policymakers here who are negotiating the future of the planet by supplying scientific information and the latest thinking about the implications of not reducing emissions.

We're worried that we could be approaching some tipping points in the climate system that could trigger some really pretty extreme events.

As we keep using lots of fossil fuel, we're worried about a big uptick in the pace of sea level rise.

(audience applauds) As we just heard, Greenland is losing ice at an accelerating pace.

Antarctica has eight times the potential to raise sea level than Greenland.

So even really small changes in that system could have really consequential impacts worldwide.

Antarctica is today being impacted by warming ocean temperatures around the edges and under the fringes of the ice sheet itself.

So it's interacting with the ocean.

Most of it is actually flowing right out to the ocean's edge and then beginning to form floating ice tongues out into the Southern Ocean.

And then calving happens, and pieces of the ice sheet break off.

This system of Antarctica, with 57 meters of potential sea level rise locked up in this massive continental-scale ice sheet with a third of the ice sheet resting on rock that is below sea level, if it were to begin to retreat back into the continental interior, it's still going to be interacting with the ocean.

Really, the key tipping point for understanding Antarctica's fate is when and if these floating ice shelves around the fringes of the continent break up, allowing the ice sheet to begin to flow faster under the ocean.

This is very much a global warming question.

If global warming gets away with us, then these ice shelves are going to be attacked both by the ocean from below, and now they could start to become covered with meltwater on the surface, and the few times that we have seen really extensive meltwater cover on ice shelves in Antarctica, those ice shelves did not last very long.

When we start to see temperatures in the summer around the edges of Antarctica that are going above freezing, we have a lot to worry about.

The ice that's lost in Antarctica you can think of as essentially permanent loss.

It will not come back because the ice shelves will not be able to reform in a warm ocean.

The land that we lose around our global coastlines because of ice loss from Antarctica will be gone essentially forever.

We have a lot to worry about.

Thank you.

(audience applauds) If sea level comes from a big loss of the Antarctic ice sheet, Boston will feel 25% more sea level rise than the global average, and that would mean that Boston will be feeling more and faster sea level rise than the rest of the world.

The potential for really dramatic sea level rise, if we think beyond the year 2100, let's say the year 2200, they're no longer three or six feet, but we'd be talking more like 15 feet of sea level rise.

And when you go even beyond that, the numbers are, some of them are as high as 30 feet or more of sea level rise in just a few centuries.

Even at the current rate of sea level rise, every year, the Seaport will be experiencing an increasing number of high tide floods.

I think we all have a moral obligation to think about future generations.

80 years from now, a lot of the Seaport is just going to be underwater, not just during high tides or extreme high tides or during storms, but all the time.

So that to me just, you know, is a recipe for disaster.

WYATT: I was sleeping here and I came here this morning.

I, I lay down, and about three minutes later, I mean, this tide rose up, like, rapidly, within five minutes.

It was at dock level in another minute and a half.

Right there.

And it usually only comes to the first cobblestone, but it's up five cobblestones.

So every time it comes up, it rises.

I guarantee you, in the next three or four months, it's going to be hitting the yellow wall next to us.

I never really thought about the sea levels rising in Boston, but this is, like, so blatantly obvious and kind of hard to ignore.

This one was weird.

It happened within a minute and a half.

I didn't see it coming, and it started springing through the middle of the dock.

I'm not going to probably be sleeping here for much longer, because, you know, it's, it's crazy, God.

Just nuts-- it's so rapid that it scares me a little bit.

That whole stack got soaked.

All my quilts, all my blankets, my pillows, some clothes that I had, that stack right there, and that's kind of important.

That quilt is a quilt that I got from an Indian family.

It's soaked and dirty.

But I'm gonna try to clean as much, much as I can.

I can probably salvage the sweatshirts, but stuff like blankets, like this, this is ruined forever.

This can't be replaced.

I had a couple of books that got ruined, because I like to go read out here so I don't go insane.

Lost quite a lot, and it's... And then, you know, it's going to be February, and I'm going to be needing that stuff.

I don't know what I'm gonna do then.

The Barking Crab's right there.

That's one of the best oyster places in Boston.

And they're flooding inside the building, probably.

So-- well, they will be.

People can't walk through here in the morning.

That changes the whole route.

Almost every jogger in South Boston jogs through here.

This is their major route.

They love coming down to the dock.

Now they can't come down here.

It's only so long before this wood gets so waterlogged, it starts rotting away.

You got to be pretty blind to not believe in climate change.

It's sad.

♪ ♪ (tool grinding) TSIPIS: The Boston Seaport is the largest private development project anywhere in Boston.

And we're about halfway done with the overall construction of the build-out here.

Certainly, this neighborhood has experienced rapid growth, and it isn't done growing.

Just over the past ten years alone the residential population in this neighborhood has more than tripled.

When we first became involved here almost 15 years ago, there was a recognition that this neighborhood would be the future of the city.

It would be the hub of the city's innovation ecosystem.

Today, the Seaport neighborhood is home to a very wide range of employers, everyone from startups to some of the largest employers in the world, like GE and Fidelity and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and many, many others.

So we anticipate that perhaps in six or eight or ten years, we'll be able to look at a more completed whole that includes about 2,500 residential homes, several million square feet of workplace, hotels, almost a million square feet of retail space, cultural and civic institutions, and about ten acres of public open space.

When we think about the development of new buildings, parks, open spaces, roadway infrastructure, we want to think about that through the lens of long-term ownership.

This is a very important place in the neighborhood.

At the new Seaport, the grade has actually been elevated almost five feet.

This is where there's a very visible example of where the new Seaport has very much been constructed through the lens of that long-term thinking.

We're here in large part because of major public investments that were made in transportation and environmental infrastructure many years ago.

Boston Harbor was one of the dirtiest urban harbors in America; today, it's one of the cleanest.

And that took billions of dollars of public investment in order to completely turn around the environmental fate of Boston Harbor.

So Boston Harbor changed very rapidly from a liability into something to be celebrated, and something around which a new neighborhood could be constructed.

♪ ♪ HOLLINGER: My name is Steve Hollinger.

I've been living in this neighborhood for 31 years.

I decided to use social media to hold the city accountable for its decision-making, with a focus mainly on allowing developers to skirt commitments and obligations on a routine basis.

(tweet posts) My goal is to elevate the dialogue in Boston about what's possible and let people understand how defective our current system is.

Broadcasting what the city was doing versus what they were saying they were doing became something I thought was valuable.

I would write letter after letter.

Letters would go nowhere.

I would attend meeting after meeting.

Steve, it looks like you have a couple of questions in the chat, and you have your hand raised.

Would you like to unmute and make a comment?

These conversations date back probably 20 years in terms of studies of inundation.

And I wonder if there's an increasing risk, as the timeline moves out, to just being inundated by a, by an unforeseen storm event.

The city has been negligent in not only planning for sea level rise and, and impacts of climate change.

The reason for that negligence is looking to the short-term revenues from development, which the city depends on, not the long-term impacts, and the developers are walking away with hundreds of millions of dollars in profits.

Where is the planning for water inland of the coastline?

If you know that water is going to enter from the coast from storm surge or sea level rise, where is that water going to go?

You have to think about all the public subsidies that are going to be needed now to protect this district from flooding.

You can't just look at property revenues for ten or 20 or 30 years.

You have to look at the life of the project.

Is the building actually gonna survive past the point where the developer makes a profit?

♪ ♪ If the developers are profiting heavily in flood zones, those developers should be expected to chip in for the mitigation of their projects.

The streets aren't raised to an elevation that's going to be protecting them from sea level rise.

So who's gonna pay for that?

♪ ♪ That little blob of grass that I would measure at roughly a quarter-acre was sold in renderings as a massive park.

And it was oversold with a lot of hyperbole while a fully approved 1.3-acre park disappeared.

Where's concern for what happens to the water that will be eventually draining off of this site?

It creates an atmosphere for very short-term thinking.

You're usually thinking in five-, ten-year increments in terms of where the dollars are gonna come from.

You're not really thinking about how you're going to protect the city from something that's 50 years away.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ (shutter clicks) PAYNE: Wow, look at that.

I started out down in the South End, near Back Bay, biked all along here, the waterfront, and I'm down there at the Fort Point Channel, and I'm looking, and I'm saying, "Gee, that's pretty high for the people, you know, walking on the other side."

And then I got here, and I go, "Wow!"

I mean, this is wild.

I just don't think we're taking this very seriously.

I mean, it's sort of a tourist attraction right now.

You know, right down there at the Chart House, it's flooded.

This is gonna get a whole lot worse.

The sea levels are rising; it's going to be catastrophic.

I, I actually don't know when people are really gonna wake up.

I'm all over the city.

When I go down to the Seaport, and every month I'm down there, there's a new glass tower that just went up.

I go down there along the Fort Point Channel down there, where GE's got its corporate headquarters, and the water is practically overflowing in their parking lot today because it's so high.

That's crazy!

Guess it's a quick buck for some people.

That's what it is.

It's, like, to turn it over.

It's like people flipping properties, and somebody else is left holding the bag.

What are the execs who were in charge of that whole project, who were in charge of GE and the Necco district and this and that, blah, blah, blah, what's going through their heads?

What do they say to each other when they look in the parking lot, it's got, like, six inches of water in it?

But that's craziness.

Absolute lunacy.

Whether we call it Inundation District, whether we call it Innovation, whether we call it Seaport, whether we, whatever the heck we call it, what are the business leaders who are actually doing the plan, what are they gonna do to mitigate?

And all those buildings are new.

The whole thing just came, rose out of nowhere.

(blows raspberry) Like that.

What of the people who live there?

What are they gonna have, inflatable rafts or surfboards or something like that, when they press the elevator and they go to lobby and there's water there?

It's a disaster for the people there.

They're buildings that will, may, may one day just crumble right in the ocean.

The ocean'll reclaim all that.

So those poor people are left kind of holding the bag.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ZY BAER: "Polarity" is a floating art project.

It is basically a sunken building, as if the rising waters and flooding of climate change has eroded its foundation.

It's sort of collapsed into the water.

My name is Zy Baer.

I'm an artist and I live and work in Fort Point.

I made "Polarity."

The title comes from the polarizing issue that is the climate crisis.

♪ ♪ Climate change is an urgent, urgent problem.

It's happening now-- it's just going to get worse.

I didn't think that it was the right time to do something abstract, or mince words or imagery.

It's time to be direct and very literal.

The climate crisis, to me, is one of the scariest things out there.

It's always been looming over me, and I think a lot of people in my generation, about what will our world look like as adults?

There's been a lot of frustration, at least for me, about talking to older people about them not feeling that same sort of fear, that at some point in our lifetime, the world may become uninhabitable.

So I just wanted to make a piece that...

It's basically show, not tell.

It's definitely an urgent issue facing South Boston, because we're surrounded by water on, on three sides.

We've already had flooding issues.

A bunch of my neighbors' cars got totaled.

People were wakeboarding through the streets being pulled by cars.

(laughing) The reason I, I used the flooding imagery for this is because, to get people to care about something, you have to hit them where it's emotionally relevant to them as individuals, and the flooding is the thing that connects to this neighborhood.

Part of this piece is the urgency of climate change, and how greatly it's going to impact the Seaport in our lifetime.

And to sort of drive that home that it's not some abstract, far-off thing.

This is what Fort Point and the Seaport could look like in a couple of decades, or maybe even sooner.

But both of these neighborhoods are going to be underwater, and what's left when those people leave and abandon the Seaport as it floods is a multibillion-dollar mess that didn't serve Boston while it was constructed and certainly won't serve Boston when it's underwater.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ VIKKI SPRUILL: Good morning, penguins!

The penguins are a crowd favorite.

The New England Aquarium literally sits at the water's edge.

We and everyone else along Boston's waterfront are vulnerable.

The New England Aquarium is adjacent to the new Seaport District.

We have been here for 53 years, but our challenges are the same.

We're all facing the threat of climate change and rising and surging seas.

It's already happening to us.

2018 was, of course, the famous king tide, and we were closed for several days and lost significant revenue.

So this is not just an environmental challenge, this is an economic challenge-- not just for us, but for all of the businesses along the waterfront.

It's urgent and it's a little scary, frankly.

In 2018, our building did not flood, but everything in front of us flooded, so people could literally not get to us, the water was so high-- that's a serious threat.

Water lapping over the edge of our wharf and flooding areas on our wharf are becoming a regular occurrence.

We see the impacts of this every single day.

We're now charting and monitoring all the king tides to be sure that we are protecting our visitors and protecting our animals.

This is not an issue where we can only be concerned about ourselves.

It does no good for developer X or developer Y to build four feet higher when everyone around them isn't doing the same thing.

What we do to protect ourselves is not enough.

She's hanging out, waiting for her breakfast.

I'm often asked what my favorite animal is, and I say, "I don't have one."

It's this giant ocean tank, where everyone gets along.

I wish humans could do that.

♪ ♪ We're doing a lot of work already to shore up our building.

It requires a lot of maintenance.

We have replaced all of our air conditioning units and put them up on the roof.

We're constantly having to care for the plaza itself.

We're trying to stay ahead of this climate challenge.

We'll be restoring the facade of this building.

This is the side of the aquarium that houses all our saltwater exhibits.

And so over time, we get this leaching and rusting.

We have to walk the talk.

We have to be willing to relocate if that means a better and more resilient, inclusive, and accessible waterfront.

That said, it would be a significant challenge for the New England Aquarium to have to move.

We care for 10,000 animals.

This is a very complex and sophisticated system.

- All right.

- Let's get on the water.

- Absolutely.

We contribute $270 million annually, where we are right now, to the economy of Boston.

So moving would be difficult, but I think we're at that point where we have to start thinking about what's right for Boston's waterfront.

At king tides, it gets all the way up.

It's quite frightening, because that water is only going to keep rising.

We don't want to move.

This is not about want anymore.

Retreat conversations are happening all over our coastlines.

You can't just up and move this like you might be able to move pieces of art.

We have to be near the water.

That is primary to our animals thriving.

This would be no small feat.

We've learned a lot from what's been developed in the Seaport District about how not to build in a climate-threatened world.

This is not a challenge for the future.

This is a challenge for now.

♪ ♪ (construction equipment whirring) TSIPIS: We believe in science.

We believe in the science that tells us that global climate change is occurring.

We believe in the science that tells us that sea level rise is resulting from that global climate change, and so we take very seriously the projections that are being made about sea level rise, about sunny-day flooding, about storm surges.

We view these buildings through the lens of generational ownership.

So we're thinking very, very long-term about how we design and construct these buildings.

So here is a 600,000- square-foot research building, and our transformer vault and our main electrical infrastructure is located on the third floor of the building.

It is a concrete-encased vault where the main power comes up from the street about 40 feet above the surrounding finished grades.

The challenge of addressing global climate change and sea level rise can't just be left to the private sector.

So we're working closely with our colleagues in government to address not just the near-term concerns about this issue, but also the very long-term concerns, which involve not only individual buildings, but also public infrastructure.

This is not a Seaport issue.

This is not a Boston issue.

It's a coastal America and a global coastal issue.

INTERVIEWER: But when you're building in a whole new neighborhood... - Mm-hmm.

INTERVIEWER: ...when you know about the risks, why should that be a public concern?

Shouldn't that be on the developers?

Shouldn't that be on the owners of the property?

TSIPIS: The reality, again, is that this is not a Seaport issue.

This is a regional issue.

And so when we talk about environmental justice and the question of who pays, we have to recognize that this is an issue that goes far beyond any particular company, any particular industry sector.

This is an issue that has to be tackled by the private sector, the public sector, institutions, public utilities, and lots of other stakeholders.

The most basic line of defense when it comes to defending against any type of flooding is to make sure that the garage entry is graded properly and is elevated off the surrounding major roadways.

This is just one of many stormwater storage tanks that we have throughout the entire neighborhood.

In aggregate, across our whole project site, we capture almost 500,000 gallons of stormwater.

And that's the equivalent of almost two-and-a-half times the giant ocean tank of New England Aquarium.

That amount of stormwater is retained in our buildings instead of finding its way directly into Boston Harbor after heavy rain events.

It's certainly our responsibility to ensure that the buildings we build are built appropriately.

But let's not forget, um, that water finds its own way.

That's why this is a question of shared commons.

This is a shared challenge between public, private, uh, and many other sectors, as well.

INTERVIEWER: So in the event there's flooding, who should pay?

That's too broad a question.

I don't, it's, I'm in the real estate business.

I can talk about our buildings and what we're doing here.

I don't, I'm not a public policymaker, so let's not, I don't want to go there.

INTERVIEWER: Can you respond to those who call this neighborhood the Inundation District?

- I, I'm not even gonna respond to that-- I'm not.

HOLLINGER: For a number of years, I tried to work collaboratively.

But I think probably by the mid-2000s, it was clear that the city was using planning as kind of a marketing tool while it was actually doing things that were other than had been planned.

I first became aware of issues relating to sea level rise and climate change probably in the late 2000s.

It became apparent that these were issues we need to think about.

Development has driven the conversation at every step of the game.

It's pretty obvious that the developers are kind of building projects that will meet their needs for a return on investment, but not long after.

One has to question what the city was thinking when they knew what the future was longer term-- why the decisions were made.

We are not taking climate change seriously in this city, there is no question.

In this district, almost the entire ZIP code is at sea level.

Everyone knows it, and construction continues unabated, with no attention to mandatory elevations, no planning of where the water goes once it's pushed away from some elevated site.

I don't envision our neighborhood is going to survive, uh, based on poor decision-making.

A lot of it could have been mitigated through responsible planning.

I think that we're gonna see lives lost.

We're gonna see significant treasure lost, in terms of public assets.

It's very frustrating for me to see the way the city has managed and continues to manage development in this neighborhood.

It's been incredibly, incredibly shortsighted.

I have multiple kayaks, so I'm not worried about surviving.

But I think the question is, who won't come out okay?

Who, ultimately, will be left holding the bag?

JOHN SULLIVAN: The tides just keep coming and coming.

They're gonna continue to rise.

They've been rising for the past 100 years, and they're rising faster now.

So, given all of that, we need to protect for it now.

We need a way to consistently, across the board, make sure we protect everything, because any opening in this sea barrier that we might design, any opening will destroy the rest of it, because the water will simply find that weakest link, it will flow in there, and then it'll inundate the entire area.

My name is John Sullivan, and I am the chief engineer of the Boston Water and Sewer Commission.

When water floods over a particular street, water can get into every manhole, and if they're not properly sealed, they can shut down all the electricity in the area.

Shutting down the electricity may shut down all the pumps in a particular building, where water's pouring into that building.

Because a lot of the systems we have weren't designed to take floodwaters.

They were designed to take a little rainwater.

But if you have an ocean sitting on top of you, it inundates you.

If it gets into the building basements, it'll flow downstairs into any open toilet and totally, totally overcome our sewer system.

The T could absolutely shut down, because you can't have floodwaters inside a tunnel.

If water gets in one portal, it can spread throughout all the portals.

One of the biggest problems is the increased precipitation.

And it's not just the amount of water that may cause flooding.

It's how quickly it gets to us.

Now, our system is designed to take what we call a ten-year storm event-- about five inches of rain over 24 hours.

The problem is intensity.

The other day, we received half an inch of rain in five minutes.

That is an incredible amount of water.

And, and the problem with that is, the systems aren't designed to take it.

Here's a typical seafront... ...along here, that easily could be accommodated to build barriers that would allow us to enjoy it as a harborwalk, yet bring it up high enough that, should sea level try to get over that wall, existing wall, which it can do with storm surge, and that would be a flooding path for this entire neighborhood, we can simply raise this harborwalk up slightly and take care of the problem.

But every pipe that enters along any of these seawalls needs to be protected, so as the tide comes in, the water doesn't come in and pop up way behind here at a lower area.

You need to protect the entire area.

So you can't build a seawall here and say, "We're done."

The seawall has to encompass you.

You need to surround the tents.

And we've been working on the development of the new building that is designed with sea level rise in mind.

And they're working with the city, collaborating with them, and building a barrier along Fort Point Channel.

This area floods very often with the very high tides.

And the, the area that floods is over where this new construction is going on right here.

Right now, it comes up over the, uh, channel sides.

It doesn't harm anybody, it sits in a parking lot.

But it's just the precursor to what's gonna be happening as the tides continually get higher and higher.

So, we're on the banks of the Fort Point Channel.

Now, when the tides come in higher, we have to make sure that the high tide doesn't come over the wall, and that is gonna be done right behind us here.

They're constructing a barrier wall to keep the daily high tides out in the channel.

The key point we have, if it's raining out and it's super-high tide, we have to make sure all the rainwater that comes from ten percent of the city that gets into this channel, trying to get out to the ocean, we have to make sure we have some place to put that water.

Our proposal is a barrier at the mouth of the channel that, at low tide, we would shut some gates.

We now have a big open basin, just as it is twice a day.

If the rain is persistent and keeps coming, we will have pumps inside the barrier.

When it starts going out, we can open up the gates, we can let the water naturally flow out.

It will be up to us as a community to figure out how we pay for it.

INTERVIEWER: How would you respond to those who say that the city was unaware that climate change would bring rising seas that could threaten the Seaport?

They may not have known the facts, and they, because you had to search them out.

We had to actually hire, um, researchers.

We had some from the University of Massachusetts, um, do some work for us to dig up what is known about sea level rise.

What is going on?

Because we were concerned enough that, from what we had read, that it was going to happen.

What were the facts?

DOUGLAS: I'm Ellen Douglas.

I'm a professor of hydrology at UMass Boston.

I've been looking at sea level rise and climate change impacts on Boston and in New England for, uh, the last 15, 16 years.

We've known that it would be bad all along.

But now we're becoming more and more certain of just how bad it's gonna be.

It's gone from computer projections to actual observations.

We're seeing, we're seeing the effects of climate change, and they're happening a lot faster than even the climate models had projected.

That's the scary part.

Boston is one of the most vulnerable cities on the planet.

The highest sea level rise that we thought, uh, would be possible in 2016 was ten-and-a-half feet.

Now we understand that it's more like 15.6 feet of sea level rise by 2100.

And so the worst-case scenario has increased by 50%.

If we were to have 15-and-a-half feet of sea level rise, the Seaport would essentially be a lot of abandoned buildings.

By 2200, it could be 55 feet.

The numbers just keep getting so big, it's not even comprehensible.

If a city has to then bail out or, or protect, um, all of these residences and all these businesses, then that's money that could have been spent on schools, it could have been spent on better building and housing for people that can't afford it.

So this is the definition of environmental injustice.

Every time we come out with a report, it's never good news.

(laughs) The numbers always seem to get worse.

The first report that I was involved in was the, um, Union of Concerned Scientists report.

It was published in July of 2007.

This report came in 2013, right after Superstorm Sandy devastated New York City.

And this report was published in 2015.

Shortly after that, the Boston Research Advisory Group report came out in 2016, and then the first update came out in 2022.

So we have 15 years of reports that have been released to the public that tell us the same thing, that sea level rise is gonna be inun, inundating many parts of Boston and that we need to be prepared for it.

♪ ♪ JARRETT BYRNES: We're actually not quite at low tide yet, but we're, we're only off by 20 minutes.

So we're hitting it right at the right time.

The goal for today, really, is to determine how different are things at this point versus when we sampled in June.

I think last time, we were going all the way out to the submerged rocks.

So let's go down and take a look and see what our low is this time.

(whoops): Oh, yeah.

This is wet and slippery.

I'm Jarrett Byrnes, I'm an associate professor at UMass Boston, uh, in the department of biology.

What we're doing here is, we're looking at the intertidal.

So, this zone all around us, uh, that's exposed as the tides recede every day.

The intertidal is this really important habitat.

It's a nursery to some species.

It's a place where other species come in and feed.

We're really interested in looking at, uh, getting a baseline where different species are.

We actually take GPS coordinates of every, uh, quadrat we sample.

As sea level rise occurs, I'm interested in seeing, um, how these species are going to change and what that means for the coast of New England.

Is it still going to be that great feeding ground for so many species?

Or is it going to change dramatically?

WOMAN: I am identifying all the algae species that I'm finding, and then I'm going through again and looking for all the mobile fauna.

You have snails, you have limpets.

Sometimes you have crabs.

And then I'm just noting how many of those there are.

In this intertidal bench that we're in here now, this is actually a really great example, um, of a place to look at sea level rise, because behind me, we have these cliffs.

There's been a lot of erosion and landslides.

And so, as sea level rises, you're going to lose more and more of this intertidal bench.

This habitat is pretty important for raising the organisms that the things that we like to eat like to eat.

We see a lot of little hermit crabs running around in here.

The hermit crabs are fed on by larger crabs.

And the larger crabs are fed on by our lobster.

If sea level rise comes up and wipes out most of the intertidal benches, the things that need this particular habitat will have to adapt or die.

BYRNES: I'm interested in seeing, um, how will those nature-based solutions, as we put them out here to mitigate the effects of sea level rise, uh, how will they change what's going on in the intertidal?

What does it mean to protect a shoreline, not just for the people that live behind those coastal defenses, but what does it mean for the ocean ecosystem of Boston and Boston Harbor?

Some form of coastal protection, some form of adaptation to sea level rise, is really necessary.

But we've got to do it right to make sure that it is, um, robust, to make sure that it is resilient to the long-term future of the coast of New England and, and Boston.

JOHN BULLARD: We're looking at the hurricane barrier, which was built from 1962 to 1966.

Any time the tides rise from a hurricane or from a storm surge, they close these massive gates, and they protect us.

I'm John Bullard, I was mayor of New Bedford from 1986 to 1992.

The reason it was built is, we had a very powerful hurricane in 1954, Hurricane Carol.

I remember boats all up on the shore.

Fishing boats, recreational boats destroyed.

They were crashing into each other.

They were crashing into all the boatyards.

There was destruction of mills and office buildings.

The devastation was, uh, incredible.

People decided that they would build a hurricane barrier that's three-and-a-half-miles- long, with three gates.

It encloses New Bedford Harbor and protects about 1,400 acres, including most of the manufacturing base of New Bedford, the entire fishing fleet, all of the downtown.

It cost about $18 million back in 1966, and it has paid for itself dozens of times over.

It protects everything in New Bedford.

The sea level's gonna rise up, but as soon as the gate closes, it's not gonna rise anymore.

The waves aren't gonna be more than two or three feet.

So there's not gonna be any damage.

I certainly see pictures of what happens in Boston on king tides, where major parts of the city are underwater.

Adaptation is something that has to happen.

You can try and retreat from the water's edge, but that's really difficult to do.

Or you can build barriers to protect the investment and infrastructure that's already there.

Everyone needs one of these.

GOLDEN: Without this kind of a system, it will be almost impossible to protect the Seaport.

In the past decade and a half, we have built over 50 buildings at sea level with no foresight in terms of the infrastructure that was necessary to protect them from sea level rise or storm surge.

In looking at the value of the investment in a sea gate system, you have to look at that value over 100 years.

It's a multi-generational investment, just like the cleanup of Boston Harbor.

You're investing now to prevent many, many times over the damages that are going to occur.

(pulleys whirring) GABRIEL CIRA: The project is about finding a coastal protection solution for urban areas like Boston, New Bedford, and other coastal cities that will enable them to adapt to rising seas.

And it does that by reducing wave energy and arresting storm surge in the most intense storm events that cause the most flooding in coastal urban areas.

My name is Gabriel Cira, I'm the project leader of the Emerald Tutu project.

Um, we're a group of, of researchers, scientists, designers, activists, urban thinkers.

The Emerald Tutu idea is a nature-based infrastructure that protects urban coastlines from flooding.

The name "the Emerald Tutu" is a kind of riff on Frederick Law Olmsted's Emerald Necklace analogy for the park system of Boston, uh, because we, we really want to underscore that infrastructure can be something new and different.

It doesn't have to be seawall.

It can kind of transform that reality.

I see our project, this kind of living infrastructure, as a replacement for the harbor-wide barrier idea.

The units themselves are wood waste and coconut fiber, and they're seeded with local marsh grass.

They basically become these living, growing, extremely heavy and dense units, and that mass reduces that wave energy and slows down storm surge.

We're seeing reduction in wave energy by up to 70%.

So imagine if the wave energy from an intense storm was reduced by 70%.

That would just reduce the damage by quite a lot.

INTERVIEWER: How heavy is it?

CIRA: This one we think is about 700 pounds, so it's hefty.

It's kind of a low-cost alternative to much more intensive gray infrastructure that require concrete, steel, earth-moving, things like that, but you could manufacture these units very, very quickly and, and keep them coming.

It could start soon-- it could start tomorrow.

We would need a lot of units to be effective.

So hundreds and thousands of units to buffer coastline as big as the Seaport, for example.

One important aspect of our project is that it's a pleasure to look at.

I would imagine it in the Seaport being a really lovely amenity for the whole neighborhood.

We show floating pathways kind of meandering through the network of interconnected biomass units.

The idea is to extend the city a little bit onto the water and allow people to enjoy themselves, to understand the relationship of the ocean and the neighborhood, while also protecting it from the effects of climate change.

♪ ♪ Everyone will have to adapt, um, and our solution will help that and take some of the pain out of that, we hope.

(group applauding) ♪ ♪ (gavel rapping) MAN: This is a great day in our city's history, as we gather together for the swearing-in of the first woman elected mayor and the first person of color elected mayor in Boston's 391-year history.

(cheering and applauding) MICHELLE WU: I, Michelle Wu, do solemnly swear... - ...that I will support... - ...that I will support... - ...the constitution... - ...the constitution... - ...of the United States.

- ...of the United States.

- So help me God.

- So help me God.

- Madam Mayor, congratulations.

(audience cheers and applauds) (playing gentle piece) WU: Boston was founded on a revolutionary promise that things don't have to be as they always were, that we can chart a new path grounded in justice and opportunity.

Over generations in this city, Boston has come together to reshape what is possible.

We're the city of revolution, civil rights, marriage equality, and yes, Boston is ready to become a Green New Deal city.

(audience cheers and applauds) (piece slows and ends) The urgency of climate change really is the lens through which we have to make decisions over the next 100 years for our kids and their kids to even have a chance.

We are uniquely vulnerable, and the urgency couldn't be more stark.

This whole area easily could be gone not too many years into the future.

A big part of the reason why we are where we are now, with a small window of time left to act on the biggest existential crisis that humankind has experienced, is because politics and government has been focused only on very, very short-term profit.

But if you take a slightly longer view, to the lives of our children and their children, we have basically created a, almost a future Atlantis.

The pressure now and the burden is on this generation to figure out how we can ensure that this doesn't happen again.

MAN: We're very happy today to have as our introductory speaker the mayor of Boston, Michelle Wu.

Part of the mayor's environmental program is Climate Ready Boston, the city's ongoing efforts to prepare for sea level rise, coastal storms, extreme precipitation, and other climate change impacts.

It is my great honor and pleasure to introduce Mayor Michelle Wu.

(audience applauds) WU: Good evening, everyone.

Our relationship with the water has always defined us.

But today, a third of the broadly defined downtown area is built on landfill, which means that as the waters rise, Mother Nature is looking to take back, uh, what was originally hers.

We need to have a public effort with how we address the built environment together, so that the burden doesn't fall only on those who can afford it versus those who can't.

We have to get ahead of this.

There will be no second chances.

The Seaport is a stark example of what we get when we're not thinking far into the future.

Morning, good morning.

- Good morning.

- How are you?

- Hi.

WHITE-HAMMOND: Good morning.

There are deep inequities in our city.

We now need much deeper social equity and environmental justice.

As we've all felt this summer, climate change is not coming, it is here right now.

It's important to me to make sure that we deal with our climate future, but in a way that supports and elevates environmental justice communities.

What we need to make sure is that the people who have done the least damage to the planet are not the ones that pay the heaviest price.

I think what you're seeing in the Seaport is not that unique in our city, in our country, in our world.

We are continuing to more or less try to leave intact a way of being we know is leading us to peril.

WU: We have to get our heads out of the sand.

We have to think about whether we are doing everything possible to make this future exist for our kids.

We have no time to waste.

♪ ♪ (chanting): News alert, it's getting hotter.

Boston will be underwater.

News alert, it's getting hotter, Boston will be underwater.

News alert, it's getting hotter.

WOMAN: What do we want?

PROTESTERS: Climate justice.

WOMAN: When do we want it?

PROTESTERS: Now.

GUTERRES: Climate activists are sometimes depicted as dangerous radicals.

But the truly dangerous radicals are the countries that are increasing the production of fossil fuels.

Investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure is moral and economic madness.

The window to prevent the worst impacts of the climate crisis is closing fast.

Greenhouse gas concentrations, sea level rise, and ocean heat have broken new records.

Half of humanity is in the danger zone from floods, droughts, extreme storms, and wildfires.

No nation is immune.

Meanwhile, many governments are dragging their feet.

This inaction has grave consequences.

We are on a fast track to climate disaster.

This is not fiction or exaggeration.

This is a climate emergency.

Climate scientists warn that we are already perilously close to tipping points that could lead to cascading and irreversible climate impacts.

Climate promises and plans must be turned into reality and action now.

Time is running out.

We have a choice: collective action or collective suicide.

It is in our hands.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Inundation District | Boston's Made Land

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep14 | 3m 29s | Did you know that Boston was once a peninsula? Nancy S. Seasholes explains how the city came to be. (3m 29s)

Inundation District | King Tide

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep14 | 59s | What are king tides? In recent years, Boston has experienced these on land more frequently. (59s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep14 | 29s | Examining the short-sighted political decisions of one American city in an era of rising seas. (29s)

Inundation District | Projecting Sea Level Rise

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep14 | 2m 10s | Climate change and ultimately, rising sea levels will impact the city of Boston and its coastline. (2m 10s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep14 | 1m 18s | Examining the short-sighted political decisions of one American city in an era of rising seas. (1m 18s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Wyncote Foundation.