Symphony of Life

Episode 101 | 51m 6sVideo has Closed Captions

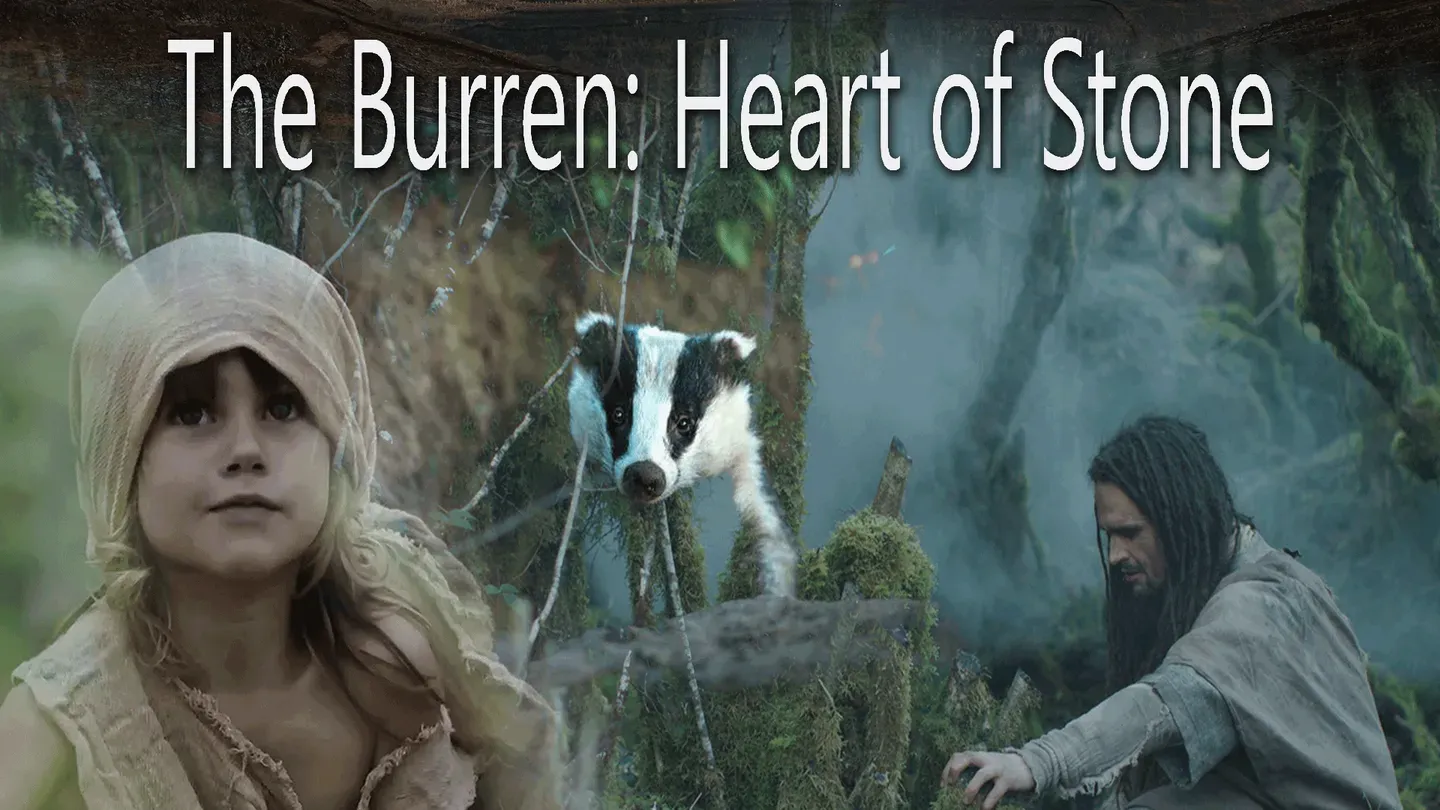

The two-part documentary series unveils the secrets hidden in the stones of the Burren.

In the countryside of County Clare, Ireland, is the Burren, a mysterious place unlike anywhere else, with deep caves, a stony landscape, and ancient dolmens, ring forts, and castles. The two-part documentary series The Burren: Heart of Stone, narrated by award-winning Irish actor Brendan Gleeson, unveils the secrets hidden in the stones of this dramatic wind-swept countryside.

The Burren: Heart of Stone is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Symphony of Life

Episode 101 | 51m 6sVideo has Closed Captions

In the countryside of County Clare, Ireland, is the Burren, a mysterious place unlike anywhere else, with deep caves, a stony landscape, and ancient dolmens, ring forts, and castles. The two-part documentary series The Burren: Heart of Stone, narrated by award-winning Irish actor Brendan Gleeson, unveils the secrets hidden in the stones of this dramatic wind-swept countryside.

How to Watch The Burren: Heart of Stone

The Burren: Heart of Stone is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

>> Funding for this series has been provided in part by the following.

♪ >> Whether traveling to Ireland for the first time or just longing to return, there's plenty more information available at Ireland.com.

♪ ♪ >> On the far west of Ireland is a place like no other.

Battered by Atlantic gales.

Sculpted into otherworldly shapes.

We call it the Burren, the "place of stone."

At first sight, it's wild and foreboding.

Empty.

But it's one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth.

This film will tell the story of the Burren.

And follow it through the seasons... to reveal how rock and weather and time have combined to shape the landscape and its inhabitants.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> More than anywhere else I've been, the Burren is not what it appears to be.

Visually, it gives the impression of a barren, kind of a sparse landscape, it's actually anything but.

♪ We're almost at the top of Mullaghmore here in the Burren, so we're between 200 and 300 meters above sea level, one of the higher points in the Burren.

Beneath your feet are the remains of millions and millions of ancient sea creatures.

It's known as limestone, but really, it's a mass grave of dead sea creatures.

So you'd have to imagine that 330, 340 million years ago this entire place was full of corals like this.

So what we're standing on now would have been like the Great Barrier Reef or like the Caribbean, just a massive coral forest.

So the question is, how do you end up with these corals in a cold northerly country 200 to 300 meters above sea level?

♪ It's the legacy of these marine creatures that's responsible for the variety of life and biodiversity that we find in the Burren today.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> What you're talking about when you mention the word biodiversity is the richness of life within an area, including all living creatures, plants, animals, insects, and humans.

♪ There are hidden pockets of a type of woodland that in Ireland are unique to the Burren, and they're called Celtic rainforests.

♪ They're like a version of the South American rainforests in that they're lush and they're damp, and they're usually in places that are very difficult for humans to access, so it's because of that they have survived in the Burren for probably thousands of years.

♪ That's the wonderful aspect of the Burren, no matter what's going on, there's still hidden gems that you can find yourself immersed in nature.

♪ Even though you think you know the landscape, there is always a new thing to be discovered, a new thing to bring joy, a new thing to look forward to every year.

The main habitats of the Burren would be the open limestone pavement habitats, the hazel woodlands, then you have calcareous grasslands in between, and then if you go down as far as the coast, you have the coastal habitats.

♪ ♪ The thread of limestone that runs through all of these diverse habitats creates this wonderful biodiversity.

♪ ♪ >> What I have here looks like a snail shell or a sea creature, but this is actually a fossil.

This is a fossil of an animal that swam around and lived here about 360 million years ago.

So way before there were mammals on the planet or dinosaurs, these creatures were swimming around, above this part of the Earth.

♪ ♪ And at the time these guys were swimming around, we were south of the equator and this area was kind of an enclosed tropical sea, something like the Caribbean.

In life, these animals had to extract this calcium carbonate from surrounding waters or from their food and then build these shells.

♪ So these creatures, as they died, the hard parts of their body, the shells and their skeletons, they drifted down to the bottom of the sea floor.

And over a period of about 40 million years, you had an accumulation of these shells and skeletal parts.

Over time, these compress, and it ends up forming limestone, which is what the Burren is made up of, layers and layers, which consist of millions and millions of these dead animal parts.

So what we've got here in the Burren is a mass accumulation of this calcium carbonate, and that in turn affects all the rest of the life we get in the Burren here.

The limestone already has the base elements that life needs, it has been taken out of the environment by these creatures -- these ancient creatures -- and stored in the limestone until it's released on the surface today.

♪ >> Look at this incredible, barren, hostile landscape.

You could be on Mars, you could be on the Moon -- how can anything possibly grow here?

The surface of the Burren is covered in these incredible, incredible features that are all really carved by the relentless rain that we have here.

And they're all very beautiful in their own way for their textures and their shapes and their forms.

Limestone is alkaline and rainwater is acidic, so when this rain lands on the limestone, it will slowly but surely eat away at the rock and you end up with all the features that you see everywhere around us.

The surface of these pavements can be quite cold, but when you get to the grykes, which are these incredible vertical cracks which run all the way through the Burren, it's a very, very different story.

Because the grykes go down a long, long way, and if plants can get a hold anywhere in these, they will be completely protected.

The grykes are like mini greenhouses, if you like.

You know, they're incredible little microclimates.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> In the Burren I think, or in any place of nature, I think the springtime has to be special.

The first sign of spring, like, it is not the greening of the leaves or the greening of the fields, the first sign of spring is actually when the light changes.

The light changes from the winter light to the spring light.

♪ It's like as if a switch was turned on from within the hills itself.

>> The conversation with all the people that are walking the hills, farmers like myself, "Did you see the gentian yet?"

There's a little competition between ourselves who sees the first gentian, or where was it seen first.

The gentian is such an incredible flower, because it comes out of the shorn Burren, where there is very little color in the surface.

With winter frost and winds and rain and so forth and the cattle has ate all of the grasses, and when that gentian comes, and that incredible blue -- it's an incredible blue -- comes out of the earth.

It is a magical plant.

Of course, as the spring unfolds, you have the early purple orchid and you have the rest of the orchids.

They come out in their turn to greet you.

There's times up on those hills when you'd see that nature at its purest and its best.

♪ There's electricity in the hills, there's an excitement in the fields, there's an excitement in the birds, there's an excitement there.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> There's something very, very wild and very, very visceral when you're out upon the hills and you see up to a hundred goats at a time.

They're so at home here.

They're so at ease.

They're so sure-footed.

They skip across the rocks and up and down cliffs and things.

They look like they've been here forever.

They look like they're perfectly suited and they're part of the landscape.

Limestone, the bedrock here, it's like a natural mineral lick.

♪ I love spending time on the hills at this time of year.

It's fresh weather, and usually you've been through the worst of the winter.

This is the season for feral goats to give birth to their kids.

I just heard this noise, and it sounded like a young kid and I wasn't sure, but anyway, I've just come across, moved closer towards the noise, and I see a nanny goat now just after giving birth to the second kid, so what I was hearing was the first kid, and I can't believe I've actually witnessed the second kid after being born.

It's amazing.

It's such a privilege to see this.

They just seem so vulnerable to me.

She might have to go away now and forage, but she'll leave them there safe, hidden in under the grass.

They've such a strong instinct to stay quiet and to stay dead still, or hear them, they don't make a little peep out of them, so you can walk right past them and you wouldn't see them, and that's a survival strategy for them to stay alive during their first week especially.

A special treat for me is when I'm out walking and I might see a nursery group.

Kids from multiple mothers all kind of hidden away.

They've been left somewhere safe while the mothers are away foraging.

Look at their eyes.

The slit pupil, it's like for good peripheral depth perception.

The sign of an animal who was predated, so they would have been eaten by wolves back in the day.

Some of the mothers are trying to keep them safe.

The time the year they're born, they're born very early in the spring, and this could be very, very dangerous in some ways because if there's a long period of harsh, cold, wet, windy weather, then they die of exposure.

50% of young goats won't make it to their first birthday.

♪ >> Wolves may have long since vanished from the Burren, but these kid goats are still vulnerable.

A red fox.

They've been known to steal the first kid goat when the second is being born.

Special whiskers on their legs help them move silently through the woodland.

♪ This vixen has a family of her own to feed.

♪ ♪ Using hollows formed by shattered limestone as their dens, foxes thrive in the Burren.

The cubs are only a few weeks old, and just starting to leave the den for the first time.

The characteristic high pounce is one of the first things cubs learn as they begin to perfect their own hunting technique.

Foxes are the Burren's top predator and are vital to the balance of the ecosystem.

♪ >> For me, the first part of spring when you see the hazel catkins begin to appear.

Particularly when the catkins begin to elongate and turn into lamb's tails as we called them as kids, and gives this beautiful golden color to the landscape.

And I see the value of hazel in our landscape in terms of its biodiversity, and also it was one of our trees that we honored in ancient Ireland.

Here we are in this beautiful woodland habitat, surrounded by powerful healing plants.

The most obvious plant we can see is this beautiful wild garlic.

There's a long history of use of garlic in Ireland, and old Brehon laws stated that anybody who was discovered to be gathering wild garlic without permission had to pay a fine of 2 and a half milch cows, so that's quite a fine.

Beside the wild garlic, we have valerian, and, of course, valerian has a long history of use as a herb to calm the mind and to stop all that overthinking.

So it's fabulous to see such a powerful healing plant right beside another wonderful healing plant -- wild garlic -- right here in this little cluster.

♪ ♪ The Burren is a wonderful place to observe the changing of the seasons.

A magnificent way to do that is to follow the march of the orchids.

Starting in the springtime when you begin to see the first orchid, which is the early purple orchid.

And when we see these flowers in springtime, it brings us great joy and it gives us a lift coming out of the wintertime, and it reminds us of all of the many wonderful flowers to come.

♪ ♪ Flowers collide together to give us a beautiful array of colors, and the scent when you're walking through the meadows or over the limestone pavement is something that you'll never forget.

♪ >> Middle of April now, and this is the time of year I've been waiting for all year.

The Burren is very magical, it's full of these beautiful flowers, and where you have amazing flowers, you have amazing insects, and then because of the insects, you get a really rich birdlife as well.

The feeling I get when I hear a cuckoo for the first time of the year, my stomach makes a complete flip and I love that it's back.

So in many places in Ireland, the iconic cuckoo call is a thing of the past, people don't hear it anymore.

[ Cuckoo calls ] And that's why the Burren is so unique and so special because the is still a stronghold for the cuckoo.

The female call's this kind of bubbly, chuckling call.

It's a very distinctive call, very different from the male's cuckoo call.

Most people have never actually seen a cuckoo.

I've been walking the hills here in the Burren since I was a young child and I've been hearing "Cuckoo, cuckoo" all my life, but it wasn't until I was just over 30 years old that I actually saw one.

[ Cuckoo calls ] And so when they come here, the males will instantly start calling and their primary focus is to breed with as many females as possible.

♪ The female cuckoo doesn't actually build her own nest at all.

She relies on the nests of other birds to lay her eggs in.

The meadow pipit.

The meadow pipit build their nests on the ground, usually well camouflaged.

Once they start laying the eggs then that's what the cuckoo's waiting for.

The perfect little incubation chamber for a cuckoo egg.

That's when you actually see that co-evolution is happening right here in the Burren.

Over thousands of years, the cuckoo started targeting the meadow pipit.

The meadow pipit then started rejecting the eggs, then the cuckoo started laying eggs that mimicked the meadow pipit eggs.

And then the meadow pipit started laying eggs with more kind of complex signatures -- you know the little squiggles on the side of the eggs -- so this led the cuckoo then to evolve and lay these really, really great forgery eggs, and it's ongoing to this day.

That's what's happening.

Like, it's been described as an arms race, right under your eyes.

♪ There's a female cuckoo just there in that tree.

A pair of meadow pipits watching it as well, keeping a close eye on her.

Cuckoos don't have it all their own way, actually.

Meadow pipits are incredibly wary of cuckoos, and if there's one in the area, they all let each other know.

All the pipits will rise and mob it.

It wants to get her out of here as soon as possible, because it knows she's a huge threat.

♪ From the time she lands on the nest, takes an egg out of the nest with her own beak, lays her own egg and flies away, that's under 10 seconds.

It all happens very, very fast, and she has to be really discrete and really quick and quiet.

She has a better chance of her egg being accepted by the host if she hasn't been seen by the host, obviously.

♪ She's just risen from the ground where the pipits are nesting, so it's possible that she just laid an egg in their nest.

>> The Burren is the go-to place in Ireland for butterflies, and the big reasons for that are the resources that the Burren has for butterflies.

It has a wealth of nectar, a super abundance of wildflowers, and, of course, not just the right food plants for the butterflies to breed on, but limestone pavement.

A butterfly needs its body temperature to be remarkably high for it to be active, so in order to raise its body temperature, it needs to bask, and they hold out their wings like that and they bask to absorb the maximum heat.

And that's how they stay active.

♪ ♪ With butterflies, it's the larval stage that's really, really sensitive, because that's the growth stage in the butterfly life cycle.

Butterflies and caterpillars look so dissimilar that people kind of wonder, "How did this maggot produce this beautiful butterfly?"

When they're about to form their chrysalis, the larva actually spins a silken pad and it attaches itself by its back legs to a surface and then it hangs with its head down.

It actually does this incredible maneuver where it flicks the larval skin away and instantaneously reattaches itself by little hooks to the silken pad that it spun.

It spends about two weeks as a chrysalis, and inside that, where's it's completely immobile, the body breaks down into kind of a soup, cells start organizing the different parts of the butterfly, and this magical transformation occurs.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ An awful lot of our butterflies live only a few days as adult butterflies, so they really, really need to get on with the serious business of finding a mate and then the females going off to look for food plants.

♪ Butterflies navigate their way through life largely through scent.

It plays a very important role in signaling to potential mates, and also even seducing mates.

Males are programmed to chase females.

That might seem simple.

It isn't.

A lot of females make males work very hard for the right to mate.

The male butterfly, he uses cells on his wings called androconial cells, and these contain pheromones.

♪ When he lands, he showers her with scent scales on his wings.

He showers them over her antennae, which are her scent organs, and she is overwhelmed with passion and she allows him to mate.

♪ ♪ ♪ >> It's mid-summer now in the Burren, and really, this place is a feast for the senses.

It's a kaleidoscope of color in the summer, and everywhere you go, there's butterflies, caterpillars, beetles, flies.

♪ ♪ I've been really looking forward to coming back to where we encountered the female cuckoo lay her egg in the spring.

The chances of that cuckoo chick that was laid in that nest surviving and actually fledging and making its own way back to Africa, it's very, very slim.

Did it survive?

I'm actually looking at the meadow pipits now and the amount of food they're bringing in, it definitely survived, I can see.

They're frantically feeding a chick in that nest right now.

They're so busy bringing him food.

Every few minutes.

It's unbelievable to watch.

It's incredible how much food the cuckoo fledgling needs.

It's a huge bird.

It's five times as big as a pipit, so...

The parents -- the meadow pipit parents -- are working tirelessly, and these are the longest days of the year here, so the poor little things, from dawn to dusk, they're bringing in food to this big, bloated cuckoo chick.

They think it's their own offspring.

That's why they feed it.

So the instinct to feed is so huge when the parents see that bright red orange beak, "Put food in here, put food in here," that's all they think, and they hear that sound.

They're stimulated by the color of the beak and they're also stimulated by the sound of the chick.

So they're following this kind of instinct to feed.

Over time, it gets bigger and bigger.

It's in the nest for 30 days being fed by these pipits, and then it fledges, and they have to look after it for another while.

And then somehow, instinctively, intuitively, it knows it must travel to Africa.

And people don't understand how it knows and how it makes this journey without being accompanied by adults, but it's just hardwired in the brain -- it must be, there's no other explanation.

♪ >> I just love the autumn time here in the Burren.

I particularly love the colors that you find during the autumn season.

I feel very much a part of the landscape during the autumn.

I feel at home.

♪ ♪ ♪ As a young botanist coming out and discovering this landscape, I decided to investigate what the land use practices were that were allowing these species to exist and that were helping these species to continue.

And I learned from this study that the ancient farming practices, traditional farming practices in the Burren were linked to the species' diversity of those plants.

>> Although the limestone here looks harsh and bare, pretty much everything that's here has adapted to a life in the Burren, including human life.

♪ Because of the properties of the limestone, the farmers here have adapted and sort of evolved an almost unique way of farming, where they're moving their cattle from low ground to high ground in the winter.

♪ When I first arrived, it didn't make sense to me.

It looked like you had cattle out on rocky ground surrounded by stone walls.

I didn't really understand how you were able to feed these cattle.

♪ Like almost everything in the Burren, it runs contrary to your expectation.

So the cattle not only survive on the high ground here in the winter, but they thrive.

They've got the nutrition that's found in all the gullies and cracks and grykes in the limestone, and they're also provided with heat that the limestone has stored over the summer months and then releases during the winter.

♪ So these areas, these mountain top areas are known as winterage, which is the opposite of almost every other farm practice on the planet.

♪ ♪ >> Thicker grasses are eaten by the cattle during the winter months, and therefore, come the following spring, these beautiful plants like the gentian and the mountain aven can flower and appear again on the landscape.

♪ The flowers are given time to flourish, to come into bloom, and then the cattle are removed from the meadows and they're brought down to the lowlands.

And this is a very important feature of the Burren.

The absence of grazing pressure allows the plants of the Burren to flower freely throughout the season right through to late autumn.

♪ There aren't many areas in Ireland now that have these kind of meadows due to changing agricultural practices.

We're very lucky in that these meadows still exist.

♪ [ Thunder rumbles ] >> Most people, when they picture the west of Ireland in winter, picture a stormy, wet, cold, damp place.

It's not always raining, but it wouldn't be uncommon to have three or four days a week with rain involved.

A large part of that is due to the presence of the gulf stream current.

It passes up along the west coast of Ireland.

This brings tons and tons of moisture-laiden air, and all of that moisture ends up getting dumped as rain and sleet.

But here in the Burren, you might notice that there's a distinct absence of groundwater -- well, very few lakes and almost no rivers flowing in the Burren.

The question is, where has all this surface water that should be on the Burren gone to?

When you're walking in the Burren, you can hear rivers running, but you can't see them, and what's happening is that they are there, but they're beneath your feet.

So when the rain falls in the Burren here, the rain water will tend to find a groove or a crack to run along, and over time, as it does this, it erodes the limestone and it forms these runnels or pathways where the water flows from the limestone, and eventually this flow of water through the cracks in the limestone forms the caves and cave systems that take all the surface water away from here.

It's a maze of waterways that flow for, in some cases, tens of kilometers underneath the surface.

Some of them are smaller, some of them seem to have been around for maybe hundreds of thousands of years, so a lot of it is still a mystery.

Some of them have been explored.

The vast majority, it's an unknown world.

Literally, nobody would have ever set foot in them.

Nobody would have ever clapped eyes on what's down there, so for these few people that do spend their time exploring it, they're really -- they're looking at things that probably no human has ever seen before.

♪ ♪ >> Cave exploration for me is mostly like Christopher Columbus setting sail and finding America.

You know, we're discovering the world under our feet.

You know, water can form these caves in very mysterious ways.

It's a whole maze of passages and sometimes very -- very unexpected twists and turns in the cave passage.

It's an out-of-this-world feeling.

♪ There is so much more to be discovered.

Above ground and below ground are completely opposite, you know, darkness and light, but yet they both rely on each other.

All the water that falls on the land gets drained by these cave systems and they're hugely important to the surface.

If we wouldn't have those natural drainage systems underground, then instead of being beautiful places we have up there right now, so it's all part of the balanced ecosystem of the Burren.

It seems quite a dark and horrible place to come to, but we bring our own lights and we shed light on secrets that have been kept for thousands of years, or millions of years, and sometimes we go to places where no human has ever been before.

Billions of cubic meters of water would have carved its way through these cracks and fissures, and sometimes it creates huge cathedral-like rooms.

Some of the places can be breathtaking.

♪ ♪ >> We've just had a really long spell of wet weather, and all of a sudden, the Burren has a different dimension to the landscape altogether.

And that is our incredible turloughs or vanishing or disappearing lakes as they're known.

Most of the time, the water in the Burren is running completely underground.

Come autumn or winter, when we've had long spells of consistent rain, the underground rivers and the cave systems become completely filled with water very often, to the point where they simply cannot take any more water running through them.

The water table becomes absolutely saturated, and of course the water has got nowhere to go, so the water is literally forced up onto the surface, and if you're in a low-lying area like this, you'll have these lakes suddenly appearing from nowhere.

When the water table goes back down again and the weather improves, then so will the water levels in the turlough and you'll be back to dry land again, so they are literally vanishing or disappearing lakes.

♪ >> The Burren is a great place for winter birds.

They come here to the west of Ireland where it's nice and temperate.

And they come -- some as early as August, September.

I did a count and I can see close to 100 whooper swans right here.

When I saw them it just kind of lifted the spirits to see all those little faces and feeding away busily after the night, and a really beautiful sight actually.

The birds just look so peaceful, and it's very tranquil as well.

It's a lovely, lovely morning.

Your waders and your ducks and geese and swans -- they're all going between the turloughs and the permanent lakes, and these places are full of tiny little microscopic life, really.

[ Honking ] They're communicating in ways that we could never fathom.

We could never understand what they're actually trying to say to each other.

That sound to me means freedom and wildness and home at the same time.

We have these sounds and we can embrace them and actually just acknowledge how much a part of our storyline they are.

I think the Burren is a huge source of inspiration for people, and not just me.

>> We call this mountain Slievenaglasha, and it's the mountain of the plenty.

It's where we live and that's where I farm and...

These mountains, like -- they're like reservoirs of heat.

The type of vegetation that grows in it, like, it's not in the power of water to destroy it.

And when the wind blows up there -- Christ, like, you know, does the wind blow up there.

There's a harshness about it.

You do your chores up there to herd the cattle, to keep the walls built, it does rattle you, like, you know?

And at the same time, it's wonderful.

You're out in the elements.

It's part of the ancestral song, the symphony of life that we were born into.

That's who we are and that's what we do and that's it, like, you know?

♪ ♪ >> By taking their cattle up onto the winterages each year, modern-day farmers are following an ancient tradition.

A tradition that illustrates how humans have adapted to the challenges and opportunities presented by the Burren.

♪ Many of the details of how our ancestors lived here have been lost, but evidence of our past in this remarkable landscape does exist.

Sometimes laid bare, sometimes hidden from sight.

It's as if the Burren wants to tell us our own human story.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> Funding for this series has been provided in part by the following.

♪ >> Whether traveling to Ireland for the first time or just longing to return, there's plenty more information available at Ireland.com.

♪

The Burren: Heart of Stone is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television