The Statue of Liberty

Episode 5 | 55m 11sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

A look at The Statue of Liberty's evolving meaning as symbol for a “nation of immigrants."

This episode explores the evolving meaning of The Statue of Liberty as symbol for a “nation of immigrants,” and how it embodies our values and our conflicts, from abolition and women’s suffrage to the treatment of refugees

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Iconic America: Our Symbols and Stories with David Rubenstein is a production of Show of Force, DMR Productions, and WETA Washington, D.C. David M. Rubenstein is the host and executive...

The Statue of Liberty

Episode 5 | 55m 11sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

This episode explores the evolving meaning of The Statue of Liberty as symbol for a “nation of immigrants,” and how it embodies our values and our conflicts, from abolition and women’s suffrage to the treatment of refugees

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Iconic America

Iconic America is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Our Symbols and Stories

David Rubenstein examines the history of America through some of its most iconic symbols, objects and places, in conversation with historical thinkers, community members and other experts. Together, they dive deep into each symbol’s history, using them as a gateway to understanding America’s past and present.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWoman, voice-over: "Stranger, I find myself lost."

♪ "Let us watch this new age gather Overhead."

"Let's see what rains onto unaccustomed skin."

[Camera shutter clicking] "This land you've sought is peopled with enemies and kin."

"You'll learn to read the whole long story..." [Camera shutter clicking] "written on skin."

"We passengers wait.

Our restless waiting forms an island."

"One woman stands, sings.

Her music enters through my skin."

"Stranger, you're the words to a hymn I've only ever hummed.

Come.

Let's erase the distance between skin and skin."

♪ David Rubenstein, voice-over: Historical symbols have a lot to say about who we were and who we have become as a people in this country.

It's hard to argue that there's a more iconic symbol of America today than the Statue of Liberty.

Man: We recognize the Statue of Liberty today as the symbol of the United States of America.

In a very real way, the statue has replaced Uncle Sam as the symbol of American life, American democracy.

It's also become a commercial symbol.

Kraut: And the Statue of Liberty has appeared in movies.

Man: Oh, OK, missy.

This ain't California.

We don't go for this stuff here.

Come on.

[Yells] ### damn you all to hell!

Man: The statue remains a powerful symbol.

It says something to everyone throughout the world.

Ronald Reagan: It's good to know that Ms. Liberty is still giving life to the dream of a new world where people of every nation could live together as one.

Man: For people around the world, the Statue of Liberty stands for freedom, which many of them, unfortunately, don't enjoy.

Newsreel announcer: The Statue of Liberty is a welcome sight.

Woman: People have latched on to the Statue of Liberty as a symbol for immigration.

Man: In many ways, the Statue of Liberty has always been aspirational.

The possibility of America, not always the actual practice of America.

Rubenstein, voice-over: When I was a kid, my parents took me to the Statue of Liberty many times and would always try to explain to me why it was so important.

The Statue of Liberty represented the story of America opening up its doors and becoming a nation of immigrants.

But recently, that story has taken a turn.

The battle over the Trump administration's zero tolerance policy on immigration is intensifying... Reporter: The Statue of Liberty says, "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free."

I don't wanna get off into a whole thing about history here, but the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of liberty enlightening the world.

It's a symbol of American liberty lighting the world.

The poem that you're referring to was added later.

It's not actually part of the original Statue of Liberty.

Rachel Scott: And the Biden administration is facing a surge at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The number of migrants is on track to reach a 20-year high.

[Ship's horn blowing] Rubenstein, voice-over: I'm curious why the statue has endured as such a popular symbol of America and why lately it's become a lightning rod for political debate.

♪ Rubenstein: When you come here, do you see people from all over New York, all over the world, typically?

Berenson: All over the world.

All over the world.

So, before tourism was cut because of COVID, at least half the people you hear are speaking foreign languages.

I take my students pretty regularly, and we do-- we do an excursion to the Statue of Liberty.

And what is their impression of the Statue of Liberty when they go?

They're amazed.

They--for one thing, they have no idea how beautiful it is.

From close up.

You know, you really have to see it close up.

Rubenstein: So, you are an expert on the Statue of Liberty.

Is that a fair summary?

I think I could say that.

Yeah.

Man: Can I ask you to sit up a bit?

David, can you sit up a little, too?

You know, you have two 72-year-old guys.

Yeah, right.

And it's hard for us to sit up straight because you're kind of-- you're slumping a little bit when you get older.

Yeah.

Well, you need a stronger back.

Right.

Yeah.

Jewish backs don't stand as strong.

There you go.

OK, you ready?

[Clears throat] So, what was the biggest surprise that you learned in your research?

Boy.

Well, I guess the biggest surprise is that the Statue of Liberty changed meaning regularly.

It's not a stable thing.

[Fireworks popping] Berenson: Early on, it was sort of a generic liberty symbol and the bid for a renewal of Franco-American relations.

Later, it got associated with immigration and a welcome to immigrants.

But it took a long time for the Statue of Liberty to become a symbol of immigration.

By the time the Statue of Liberty went up in 1886, immigration was already becoming very controversial.

Huge numbers of immigrants were pouring in from Europe and mainly parts of Europe where immigrants hadn't come from before-- Southern and Eastern Europe.

And there was a lot of criticism that these people are "the riffraff of Europe.

We don't really want them."

And the first idea that government officials had was that it was to locate the immigration processing center on the same island as the Statue of Liberty.

And that produced an uproar.

All kinds of stuff about the Statue of Liberty as a symbol of the purity of the United States.

"How dare you dump all these European refugees at her feet?"

And so, you put it next door on Ellis Island.

♪ Rubenstein: When did they stop using Ellis Island as an immigration center?

Caitlin Dickerson: By the thirties, Ellis Island was primarily a detention center.

And then I think it was the mid-fifties when they shut it down completely.

And then it was vacant for several years before they used it as a museum.

So, from this building in Ellis Island, you can see the, uh, Statue of Liberty?

Dickerson: Yeah.

Wow.

Definitely one of the most well-known icons in the United States, probably...

Right.

the most well-known.

It's interesting.

She is a very powerful symbol.

You know, she's not in Central Park, she's not downtown.

She's actually on the water literally welcoming people and holding up a torch as if to say, you know, "Come on in.

I'll show you the way."

I think the way that the statue looks and what it says just lends itself to this immigration narrative so easily that it was co-opted.

Right.

Shall we?

♪ Dickerson: What's interesting about these pictures to me is that they really showcase how difficult the immigration story is.

So often it's glossed over and kind of romanticized in the way that we tell it.

But you can see in people's faces-- I mean, they look exhausted, they look really run-down.

And yet at the same time, you also see people who look like they wore their very best clothes...

Right... to come to the United States.

Right.

Rubenstein: I can't imagine how those circumstances were on the boat.

I assume they weren't exactly in first class.

Right.

Interestingly, today, when people have pictures taken of them, they generally smile.

Yeah.

But you don't see people smiling so much in these pictures.

When you think about it, you've lived your whole life in a country and all of a sudden, you're picking up, taking whatever possession you have with you.

You're going to another country you've never been to before.

In some cases, you have no relatives there.

It's a pretty daunting, uh, experience.

And I don't know whether I would've done it in the same circumstances.

I don't know whether I would have, either.

I mean, immigrating, it often, it becomes the defining feature of a person's life, especially those who feel like they've done it because they have no other choice.

Their immigration story becomes their-- the story of their life.

Right.

Coming from the French West Indies.

Wow.

Dickerson: Coming in what year?

1911.

You don't really think about, uh, a lot of immigration from the French West Indies then, but... We don't.

it obviously occurred.

Rubenstein: So, why is it that Ellis Island became so famous?

A lot of people came from, let's say, Latin America, Mexico, Asia, and not everybody who came from Europe came to Ellis Island.

What is it about Ellis Island that became so famous?

Ellis Island is very close to the Statue of Liberty, which is a very important symbol in our country's immigration history, and it was an incredibly busy port of entry.

You know, at Ellis Island, there were years when more than a million immigrants were processed at one location.

Those numbers are unheard of, even today, along the Southern border.

It's a place where many, many, many Americans can trace their history to.

And I think that's why it has such a powerful reputation.

Now, when I was in school as a young boy, I remember my teacher saying we're a nation of immigrants, but is that right?

I would say that we are a nation of immigrants, that we have larger numbers of immigrants than any other country in the world.

And yet, exclusion is as much a part of our history as allowing people in and welcoming them.

Rubenstein: What do you think the Statue of Liberty really symbolizes and really represents to Americans?

I think the Statue of Liberty has had a lot of different meanings, from immigration and a welcome to immigrants to freedom during the Second World War in the face of fascism, but when the Statue of Liberty was first conceived, what it's supposed to symbolize is the abolition of slavery.

Oh, wow.

But nobody knows that story.

Rubenstein, voice-over: I had never heard that the Statue of Liberty had ties to abolition and was curious about this surprising connection.

Kraut: You know, David, one of the things that people often don't understand is the origins of the Statue of Liberty.

If we take a look at the statue, there is a little piece of chain under the left foot of the statue.

That's all you can see of what was originally the crushing of the chains of bondage by Ms. Liberty, which symbolized the ending of slavery.

Kraut: The idea came out of the head of Edouard Laboulaye, who was a French expert in constitutionalism and politics, a great admirer of Abraham Lincoln, an advocate of emancipation.

And after the assassination, he wanted a way to celebrate Lincoln's legacy and the emancipation of the slaves.

And it's really quite fascinating to see the development of the concept of the statue and what happens to the chains of bondage, which had once been, at least in early representations, present in the hands of the statue, is reduced to the foot of the statue.

Rubenstein: Wow.

Rubenstein, voice-over: James Baldwin once said that history makes the present complete.

I wanted to investigate more about the history of the statue's origins with my friend Lonnie Bunch, head of the Smithsonian Institution.

Rubenstein: I did not know that the Statue of Liberty had any connection to abolition and Reconstruction.

I thought I knew a lot about history, but I didn't know that.

Lonnie Bunch: Yes.

When the idea was conceived, it was a celebration of emancipation.

But there was little attempt as the design evolved to continue to tell the story of abolitionism.

And in a way, it is interesting that it's so high up that you rarely can see it even if you're looking for it.

Bunch: I think you tell a great deal about a country by what it remembers.

And monuments are a concrete way of remembering.

You also learn a lot about a country by what it forgets.

And I'm fascinated that where we are as a nation is really grappling with, What is good history?

Um, what should we know?

What should we remember?

Bunch: The story of the initial conception is little known.

The notion that the leader of the French Anti-Slavery Society really wanted to celebrate Abraham Lincoln and celebrate the abolition of slavery.

Bunch: But over time, as people began to think about what the ultimate final design would be, abolitionism slowly, um, became less important.

By 1886, the United States had given up on sort of bringing the North and South together, including African-Americans.

The belief was that you eliminate them, the nation can come back together, you know, the notion of brother versus brother.

And so, there wasn't a real interest to talk about slavery.

So, this really became a symbol that was available to be embraced for other things.

And Lady Liberty became a symbol of America being the beacon to the world.

Rubenstein: As events unfolded, the design of the Statue of Liberty changed.

Rather than chains, she was supposed to hold the Declaration of Independence.

Whose idea was that?

The sculptor.

This was all about Bartholdi's vision.

Rubenstein: So, it was Laboulaye's idea, but how did Mr. Bartholdi get involved?

Kraut: Legend goes that at a dinner party in the summer of 1865, Laboulaye talked with a friend named Bartholdi about his idea, that he would like a gift from the people of France to the people of the United States and that it might be some kind of a statue.

Rubenstein: Was he a well-known abolitionist in France?

Kraut: Bartholdi, uh, was not a political operative.

He was an artist.

He loved large sculpture.

At one point, he actually proposed a huge piece of sculpture that would straddle the Suez Canal.

That project never got built.

But he was somebody who liked very large pieces of sculpture, and the project intrigued him.

Rubenstein, voice-over: I wanted to better understand what events in history could have so dramatically altered the meaning of one of the world's most iconic statues.

The statue was designed and constructed in Paris, and one of France's leading historians has closely studied the shifting nature of symbols, including Lady Liberty.

Man: This museum was inaugurated 90 years ago for the French colonial exhibit.

The purpose was really to convince the French visitors that colonization was good, that it was something good for those being colonized.

So, it was propaganda, obviously.

But now, this museum is the national museum of immigration that opened 15 years ago.

So, this building has a very different purpose from what it had 90 years ago.

Historians such as myself have studied symbols, especially a highly visible monument such as the Statue of Liberty, in order to understand how a society becomes a society, how people feel from a given city or a given country.

In France, there's no symbol that could be compared to the Statue of Liberty.

That is why I and a few others are dreaming to build something, to have something.

So, you're not suggesting that some people in the United States should take a collection up and build a Statue of Liberty in France as a way to thank France for building the Statue of Liberty in our country?

What a great idea, David.

You should think about it.

You should be the, uh, Laboulaye of the 21st century.

You know, that's a great idea.

All right.

I'm gonna think about it.

Rubenstein: When the Statue of Liberty was proposed, were many people in France supportive of that?

Ndiaye: In the mid-1860s, no one had heard of this project.

It was too bizarre, in many ways too disconnected from the lives of most French people.

So, it remained within a small circle of wealthy elitist dreamers.

But it started to generate a wide interest in France, when the statue itself started to be built right in Paris, when the Parisians started to see the gigantic arms of the statue popping out of the Parisian skyline.

So, the reality of it really struck the French, but this came so late in the whole process.

What were the currents going through French politics in the 1860s and 1870s that would have led somebody to say there should be a Statue of Liberty in the United States?

When Bartholdi and his friends met in 1865, they did so as to celebrate the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, but to Bartholdi and others, this had a wider meaning in some ways.

It meant being free of the old bondage that existed in many countries.

It has a highly symbolic dimension so that anyone can think of something that the statue has a kind of universal meaning, so, this statue is vague enough to please everyone.

It is also vague enough to displease a lot of people.

Rubenstein, voice-over: America's greatest symbol has its roots in a small town in France about 300 miles from Paris, where Bartholdi was born and first conceived of his vision for the statue.

There's no better way to understand the statue's evolution than to go where it all began.

♪ So, this is the replica of the Statue of Liberty.

It was erected here to honor Auguste Bartholdi.

He was born in this city.

Where this is now located appears to be a transportation and logistics center, because every truck coming by in the world seems to be here, but it looks exactly like the one in New York Harbor, down to the chains at the feet.

And we can see them here very closely.

Rubenstein: So, they erected a Statue of Liberty right in a traffic circle area of the city.

Why did they do that?

[Chuckles] Uh, uh, I prefer not to commend this decision because I don't think it is a very good decision.

It would be better to develop the Museum of Bartholdi in Colmar, but it's my own, uh, impression.

Rubenstein: Now, this museum was his original house.

This is where he was born.

Is that correct?

Yeah, absolutely correct.

Rubenstein: So, you've been in this museum many times?

Belot: Yes, many times for my research to write my biography of Bartholdi.

The museum opened in 1922.

Rubenstein: And it operated until World War II?

Belot: It was closed because of the German occupation, you see.

And Bartholdi was a symbol of French patriotism.

Rubenstein: So, in here we have the, uh, statue that was originally designed for the Suez Canal.

Yes, right.

In 1869, in fact.

It was designed to be a lighthouse.

But it was a model only because Isma'il Pasha, who was the khedive of Egypt, uh, has no more money to finance this statue, so...

But this statue looks a little bit like the Statue of Liberty, doesn't it?

Yes, absolutely.

And after, this project has been reused for the Statue of Liberty in New York, in fact.

Wow.

And that right here is the first model of this?

It is a very first model created in 1870.

And the difference is the chain, you know, the chain.

And after this model, you have the very first model, uh, with the tablet.

It's new from this one, too.

You have the chain and the tablet.

Rubenstein: Very impressive.

Yeah, yes.

Rubenstein: Now, what are the chains designed to symbolize?

Belot: It symbolizes the fight against authoritarianism, fight against monarchy.

Rubenstein: Some people say the chains are designed to symbolize the end of slavery in the United States.

Is that part of the symbolism as well?

Yeah.

Yeah, the chains themselves symbolize slavery and the broken chains, the end of slavery.

But Bartholdi developed the idea, you see.

Rubenstein: It was Laboulaye's idea to do something like this.

Belot: Uh, yes.

It was him who gave the idea one week after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln to imagine a very big symbol of the friendship between America and France.

So, the idea was Laboulaye, but the realization was Bartholdi's.

And Bartholdi was very inspired by the comparison between the French regime and the American regime.

And at the time during the Second Empire with Napoleon III, it was not a very liberal regime.

They wanted to fight for liberty, so, it has a political signification.

But you can interpret it as you want.

There is not only one interpretation, in fact.

Why do you think some people think that the chains are more important in the statue than they are now when they're at her feet?

Um, the Statue of Liberty has always inspired fake news, you see... [Chuckles] from the beginning to now.

So, for me, it's fake news, you see.

I see.

You are free to imagine what you want to imagine.

Rubenstein, voice-over: Bartholdi's biographer believes there was no intention to diminish the abolitionist symbolism by moving the chains under her foot.

Rubenstein: There's a rare work that was recently discovered by the Metropolitan Museum of Art that may hold more clues.

Ah.

There she is.

Rubenstein: So, there is a story that, uh, when the Statue of Liberty was being conceived, that the chains were a more important part of the Statue of Liberty as originally conceived.

I think there is truth to that.

I mean, nobody knows for sure.

But if you look at other representations of liberty in France, for example, broken chains are a central part of those representations.

So, it makes sense to think that something designed by a French sculptor like Bartholdi would also have those chains prominently displayed.

♪ Woman: This is a presentation drawing by Bartholdi of the Statue of Liberty illuminating the bay.

Rubenstein: So, this is a number of years before the Statue of Liberty was actually built.

Indeed.

Yes.

This is a drawing that was meant to inspire people.

Um, they created this drawing with the idea of presenting this to the American people, who were supposed to pay for the pedestal.

Rubenstein: Now, here you see some chains.

Woman: Indeed.

They were there quite visibly in her hand, and eventually they moved down to under her foot.

And why do you think they were dropped?

Woman: So, I spoke before about the American people being responsible for paying for the pedestal.

And I think part of getting buy-in for people to want to do that was to maybe downsize the kind of political, the loaded meaning of the statue into something that was kind of more generic.

That's a very important point.

Basically, getting rid of the chains means excluding African-Americans from the statue... Speelberg: Yeah.

from the meaning of the statue.

So, constructing, uh, an idea of liberty that excluded African-Americans because it excluded the thing that symbolized their liberty, the broken chain.

Rubenstein: Let's pretend for a moment that this was actually the version that was built where the chains symbolizing the breaking of the bonds of slavery had actually been in the left hand of the Statue of Liberty.

Do you think that would have changed history in any way?

Stovall: I think it could have.

I think it would have made it much more difficult to exclude the idea of slave liberation from the broader American narrative of America as a land of liberty.

And having a symbol so central to the United States symbolize slave liberation, as it would have done, would, I think, have placed the concerns of African-Americans much more centrally in American history.

Rubenstein: As you look at the Statue of Liberty today, as an American, do you regard it as an important symbol of our country, or do you look at it as a flawed symbol of our country?

I think it's both.

I mean, I think it is an important symbol of our country.

And it's a symbol of the ways in which freedom has often been entangled with whiteness.

I don't think you can-- I would certainly not advocate getting rid of it, for example, because it's a major part of American history.

And the changing images of it are a major part of American history.

It's certainly important to me.

It's important as a symbol of everything that is intrinsically interesting about America, right, both the good sides and the bad sides.

And I think the fact that it does have this multiple kinds of symbolism to it, I think is really fascinating, so, let me just say I'm glad it's there.

Rubenstein: Is the Statue of Liberty a symbol of the United States in your mind?

Yes.

Absolutely, absolutely.

Why?

Because so many people around the world and in this country see the United States, rightly, wrongly, as the central place of freedom, and so, the Statue of Liberty stands for that.

I mean, it's just been so many things and what you often see is symbols changing over time because each historical era puts its own stamp on a monument or some symbol, and that's, I think, the way it should be.

Rubenstein: When you see the Statue of Liberty now, what does it mean to you?

Ndiaye: To me, it's powerfully related to immigration and to the fact that in spite of the fact that the U.S. are not the land of freedom for everyone, the statue remains a powerful symbol.

Are you surprised at the way symbols sometimes change?

For sure.

Look at this, uh, monument where we are in.

It was built to promote colonization, to symbolize the greatness of the French empire.

And now it has a completely different meaning.

We have the National Museum in the History of Immigration, which is, uh, the equivalent of Ellis Island in many ways with the purpose of, uh, promoting the history of immigration and convincing the French that immigration is as important in our country as it is in the United States.

And the poem by Emma Lazarus played an important role as well as the migrants themselves who were having a look at the statue when miles offshore when arriving to New York, so, they started to make this powerful connection between the statue and their new life in the United States.

Rubenstein: So, to what extent do you think the meaning of the entire Statue of Liberty has been changed by the words of Emma Lazarus?

Woman: Emma Lazarus utterly changed the meaning of the statue.

Uh, the idea of the statue was that it was a tribute to Franco-American friendship, to freedom, abolitionism, French republicanism.

And Lazarus changed it in 14 lines of writing into a statue about immigration.

How did Emma Lazarus get connected with the pedestal?

Emma Lazarus was asked to contribute a poem to a portfolio of original writings that was going to be auctioned off in December of 1883 to raise money for the pedestal.

Schor: It was called the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund.

And Emma Lazarus at first said, "I don't write to order.

I don't think I'm going to do this."

But Emma Lazarus did write the poem, and it was auctioned.

It was published in a small magazine and completely faded from view.

Schor: She died in 1887, and in 1903, her friend Georgina Schuyler wanted to make a tribute to Emma Lazarus and decided to get the poem put on a plaque and put in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

And there it fades from view again.

After World War I, there was this period of strong nativism and anti-immigrant feelings.

And it was only in the following decade, the 1930s, that pro-immigrationists seized on her poem as a poem that was resonant, a poem that could open lectures, a poem that could be put on letterhead.

And from thereon in, the poem sort of has steadily gained ground as a central poem for Americans.

And I would add that the poem began as a kind of subversive poem.

It's part of the period in which she's working for Russian Jewish refugees.

So, she's talking about refugees, and Emma Lazarus was actually very disappointed in her attempts to raise money, uh, from American Jews for the refugees.

So, what she did was generalize the appeal to an appeal to all Americans about all immigrants.

Rubenstein: So, where are we now?

Woman: We are in the stacks of the American Jewish Historical Society archive.

Rubenstein: What's the most valuable thing in your collection?

Well, that would be-- that would be hard for us to say, but we are certainly going to look at one of them.

Rubenstein: So, this is from the Emma Lazarus collection?

Woman: That is correct.

Yes.

This book is an original manuscript copy of Emma Lazarus' poems written in her own hand towards the very end of her life.

So, she purchased this book, actually right here on 6th Avenue, and then, uh, decided to write down her own poems in the order in which we assume she found to be the most significant or meaningful to her.

What was number one?

It was "The New Colossus."

Schor: She starts it with "The New Colossus."

I just don't want to take that for granted.

I mean, she felt that this was her most important poem and there was nothing else in the world to tell her that.

She simply knew it for herself.

Rubenstein: But, of course, when she wrote this, she didn't know that this poem would actually be on the Statue of Liberty.

Is that right?

No, not at all.

I mean, uh, she wrote it, as she says here, to raise money for the pedestal.

So, here's "The New Colossus," page one, number one.

Schor: "Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land..." Schor: "Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand "a mighty woman with a torch, "whose flame is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles."

Tracy K. Smith: "From her beacon-hand "glows world-wide welcome.

"Her mild eyes command the air-bridged harbor "that twin cities frame.

"'Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!'"

"cries she with silent lips.

"'Give me your tired, your poor, "'your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

"'The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

"'Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!'"

Rubenstein, voice-over: Emma Lazarus seems to have had remarkable foresight.

The power of her poem, combined with the proximity of what would become the main passageway for immigrants, redefined the statue and history.

A site where immigrants stayed on Ellis Island, now closed to the public, holds clues to how they were treated here.

Man: So, now we're leaving the museum and we're gonna go to, uh, something that not many people get to see, the baggage and dormitory building that had more facilities for people who were being kept more than one day, for--basically for food and lodging.

Hnedak: OK. Now maybe it's time for the hardhat.

OK. Hnedak: Here we go.

♪ Rubenstein: This is the dormitory.

Hnedak: Well, we're probably in more of like a storage area right now.

You see some historic photographs of how much baggage came through.

And even these individuals had huge, you know, bales of things.

Dickerson: I mean, they brought everything they had.

No, they brought everything they could.

It's not quite the same thing.

Hnedak: We're gonna go up those stairs.

So, careful here.

Um, let me go first.

OK.

Here's the spot, so be careful.

Hnedak: This is probably a dormitory room.

Hnedak: So, they had music.

There was two pianos here.

There are a number of pianos in our collection, that none of them are in good shape.

It's kind of tragic, but it's also kind of cool-looking.

There was music all over the place.

Dickerson: Really?

Hnedak: Yeah.

I mean, I think people who worked here were very conscientious about trying to make people feel comfortable where they were.

And it was not an easy time.

It couldn't possibly have been easy for people because there's a lot of fear involved... Dickerson: It actually was probably pretty cool for musicians from all over the world to hear each other work and maybe get inspired by each other.

Hnedak: You know, use your imagination.

They heard something from Poland or somebody from Spain.

You know, who knows?

Dickerson: Yeah.

But, uh, people find each other.

That's the thing.

Dickerson: Yeah.

These little things make a big difference.

Hnedak: OK. And then go through.

OK, fine.

You ready?

Rubenstein: Yeah, ready.

Hnedak: OK. Let's go.

Hnedak: What do you think?

Dickerson: Wow!

[Chuckles] I know.

So, this was--this is, you know, kind of a hangout.

Dickerson: This is incredible.

What a welcome... Yeah.

to a new country.

Hnedak: What would have been a big deck, a paved surface with railings around it.

And it was a recreation kind of place.

People, this was for the immigrants, those people who were detained here.

They could go outside and enjoy the fresh air.

So, once again, that's a story about, um, how people were treated.

♪ Rubenstein: How would you compare what happens today to immigrants coming to our borders legally or illegally with what happened at Ellis Island?

Kraut: Well, family reunification was a very, very important issue.

And there was a rather extensive staff on Ellis Island who helped immigrants find their relatives and find safe places to stay.

Now, we all know the story of the separation of children from their parents at the borders.

Inside this old warehouse in South Texas, the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol is keeping hundreds of immigrant children in cages created by metal fencing.

Kraut: Some of us, myself included, found the behavior despicable.

And we are in a moment in American immigration history when there's a great deal of controversy over how to treat newcomers and how to pursue reform of American immigration policy.

Reporter: An estimated 7,000 migrants have entered into Arizona since last Thursday.

Kraut: Today's situation is a very complicated one.

And it's complicated by the reality of the large numbers of unauthorized immigrants.

And the United States has had enormous difficulty in terms of controlling that unauthorized flow.

It seeks to do that and emphasizes the importance of coming in an authorized and legal fashion, but nevertheless, the unauthorized continue to want to come.

Alejandro Mayorkas: The border is not open, and there are alternative paths to seek humanitarian relief.

The largest group of migrants and asylum seekers apprehended, 1,036 people crossing near El Paso.

Man: Our message is, we're not criminals.

We're coming over here because we wanna work.

We need a job.

We need better, you know, a better life.

Man: The Statue of Liberty has some positive elements, but within those positive elements, there's a very long history of who gets to decide who comes into this country and who doesn't.

Historically, local newspapers here in El Paso referred to all of this as the other Ellis Island.

And my great-aunt was the first person that told me about these very humiliating baths that she had to take whenever she would cross from Juarez to El Paso.

I thought maybe her memory isn't completely there.

But I was able to confirm it later.

My great-aunt's story is correct.

So, this is the processing center here at the Rio Vista Bracero Reception Center.

So, between 1951 and 1964, 700,000 braceros came through here... [Man speaking indistinctly] Dorado Romo: specifically with the Bracero Program, the Mexican guest worker program, that started in World War II.

And this was at a time where America desperately needed Mexican workers because of the war.

Processing meant being poked, searched for contraband, X-rayed, vaccinated, fingerprinted, interrogated, stripped, groped, and herded.

And then sometimes you would have the farmers come here and touch their muscles.

So, you see these photographs of people being almost treated like cattle.

[Indistinct chatter] Dorado Romo: All of this happened here.

So, this is usually not open to the public.

So, this is the Quonset hut that was used in this particular location where they were fumigated with DDT, which is extremely noxious and potentially causes cancer.

And when they would come out from the other door, they said that their bodies were all white.

It was quite a harrowing experience for them.

Dorado Romo: Things like this took place for many decades.

This history is absolutely not taught either at the local or at the national level.

It's been erased from the books, the history books, the schoolbooks.

Dorado Romo: Whether you lived here in El Paso or in other parts of the U.S., you would have absolutely no knowledge that ever happened.

Part of the collective mythology of what America is, is this idea that immigrants come here from across the ocean.

They see the Statue of Liberty, and she's welcoming people.

When an immigrant comes today, the first thing that he's gonna see are those fences.

You're gonna see armed people.

You're gonna see an attitude not of openness.

There is no Statue of Liberty here greeting you.

Sometimes people say, "Well, why can't we go back to that "golden age of immigration, where our policies were not based on racism and contempt?"

And as an historian, I say, tell me when that ever happened.

My great-aunt was going through this in 1917.

So, when was this golden age of open-arm immigration policies that we want to go back to?

And I think, unfortunately, the Statue of Liberty now has become almost inextricably intertwined with that oversimplification.

Wolf Blitzer: Cruel, inhumane, atrocious, and heartbreaking.

Those are just some of the words being used to describe this immigration practice now of separating children from their parents.

Adding to the outrage, pictures from inside a detention center showing some of those children housed in chain-like cages.

♪ Jim Sciutto: ...thank you very much.

And there you have it.

This is a protest on July 4th at the Statue of Liberty, which-- with a poem, which reads in part, "Give us your tired and poor," and that protest about immigration, ICE, family separation, et cetera.

Woman: It was the 4th of July, and we were protesting the family separation that was unfair to immigrants at the Southern border.

Reporter: It began with a group calling itself Rise and Resist, posing in T-shirts reading "Abolish ICE," then dropping a banner from the base of the statue reading the same.

Woman: The message was important.

It was not a joke.

It was serious.

There were children in cages.

Woman: Oh, you guys are so beautiful.

Okoumou: Officers were asking us to remove the banners.

They were taking us into custody.

They went into one direction to the right, I went up to the left.

Reporter: Seven of them arrested, and suddenly police realized they had a climber on Lady Liberty herself.

Okoumou: So, I walked to this, what I call, balcony.

From this balcony, I jump to the statue, and I hung onto it, and I pulled my body up.

[Speaking indistinctly] Okoumou: I was trying to keep my body low and not stand, afraid that the wind can blow me off.

It was very high, and it was windy.

I found an area where I can sit down and relax.

Reporter: Her dramatic demonstration playing out just above the statue's pedestal.

That's 154 feet up in the air.

Okoumou: I had no idea that I was being watched by millions of people.

It was because personally, I felt it was necessary.

When it comes to children, tender-aged children, it's just awful.

There was too much at stake.

Reporter: It took 3 1/2 hours to get to this point.

Chopper 4 overhead as the NYPD's ESU Unit made the grab of a demonstrator who had told them she wouldn't come down until "All the children are released."

Okoumou: I knew I was going to get arrested, but I didn't know I would be punished for climbing.

Afterwards, when the judge found me guilty, sentenced me, I took the punishment.

And right now, I'm facing--I'm going-- undergoing my 5-year probation.

[Cheering and applause] Okoumou: I really thought the media would take me seriously because I was dead serious.

But I became known as the hashtag Statue of Liberty climber, not the woman who was trying to free the children from the cages.

I believe in the people's power if we come together for a common cause.

Immigration is a huge issue.

[Crowd chanting "Shame!"]

Okoumou: I thought I was going to make a change.

But I felt, kind of, some disappointment.

Sometimes things just repeat themselves.

We take a long time to better ourselves as far as our immigration policies.

♪ Smith: A monument isn't a policy, but it's an object toward which our vocabulary and our feelings, our hopes, and even our anxieties, can be projected.

And so, maybe it's a site where some of the difficult reflection and admission could begin to happen.

Smith: But it's hard to get into conversations about the reality of American history without being questioned about being anti-American, about, you know, being somebody who, who wants to undo all of the good that so many people did.

Smith: I think everything has the opportunity to evolve.

Maybe a Statue of Liberty can be not only an impetus to dialogue and conversation, but I imagine that talking through these things in good faith could be incredibly productive and even a little bit healing.

Dickerson: I've had new immigrants to the United States tell me that they have dreamed their whole lives of coming to New York City and visiting the Statue of Liberty.

Dickerson: The statue, in their minds, it represents the version of the United States that these new immigrants want to be a part of, that they believe in, that they sacrificed in order to reach.

Man: Candidates, please raise your right hand and repeat after me.

I will support and defend...

Candidates: I will support and defend... Man: the Constitution and laws...

Candidates: the Constitution and laws... Man: of the United States of America.

Dickerson: And so, I do think the Statue of Liberty is still very important in the minds of both immigrants and Americans who already live here.

Man: Congratulations.

[Cheers and applause] Dickerson: The reality and why so many people from all over the world continue to try to come here is because they hold on to that idea of the United States that they want to be a part of.

They hold on to the values that we state as a nation, even if we don't always live up to them.

Dickerson: And it's also the case that the United States continues to be a land of opportunity.

Rubenstein, voice-over: Through unpredictable events in history, the statue became a symbol of the great migration, millions of immigrants seeking a better life.

Some would become the greatest thinkers, artists, and inventors of our time.

Over 135 years later, America still holds that promise as a priority destination for immigrants around the world.

Joe Biden: You've each come to America from different circumstances.

And like previous generations of immigrants, there's one trait you all share in common: courage.

Rubenstein, voice-over: While this country struggles at times with the ideals it embodies, the Statue of Liberty still serves as a powerful reminder of the unique and remarkable achievements of the American experiment.

♪ Announcer: Explore more about "Iconic America" at pbs.org/iconicamerica.

Join the conversation with #IconicAmericaPBS and stream more episodes of "Iconic America" on the PBS app.

"Iconic America" is also available for download from Amazon Prime Video.

♪

A Catalyst for Reflection on Our Past Transgressions

Video has Closed Captions

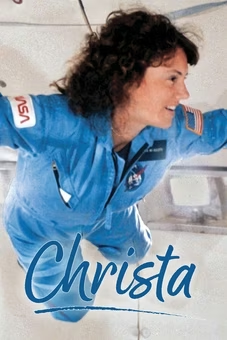

Clip: Ep5 | 1m 6s | Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith reflects on Lady Liberty's potential as an agent of change. (1m 6s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep5 | 3m 56s | America's greatest symbol has its roots in a small town in France, 300 miles from Paris. (3m 56s)

How the Statue of Liberty's Anti-Slavery Origins Evolved

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep5 | 3m 41s | A look at how Lady Liberty's anti-slavery origins and design changed over time. (3m 41s)

A Poem for All Americans, About Immigration

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep5 | 55s | A look at how the poem, "The New Colossus" came to be engraved on the Statue of Liberty. (55s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep5 | 31s | It's hard to argue that there's a more iconic symbol of America than the Statue of Liberty (31s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep5 | 47s | David Rubenstein asks Professor Ed Berenson why Lady Liberty is a symbol of America. (47s)

"Their Immigration Story Becomes the Story of Their Life"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep5 | 2m 45s | David Rubenstein visits Ellis Island with Atlantic writer Caitlin Dickerson. (2m 45s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Iconic America: Our Symbols and Stories with David Rubenstein is a production of Show of Force, DMR Productions, and WETA Washington, D.C. David M. Rubenstein is the host and executive...