April 24, 2025

4/24/2025 | 55m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Zvi Solow; Selma van de Perre; Elie Wiesel; Zahra Joya; Jonathan Blitzer

Holocaust survivor Zvi Solow reflects on the 80 years since the liberation of Auschwitz -- and antisemitism today. A look back at Christiane's conversations with WWII resistance fighter Selma van de Perre and Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. Zahra Joya on her mission to "give a voice to the women of Afghanistan." Jonathan Blitzer on Trump's immigration crackdowns.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

April 24, 2025

4/24/2025 | 55m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Holocaust survivor Zvi Solow reflects on the 80 years since the liberation of Auschwitz -- and antisemitism today. A look back at Christiane's conversations with WWII resistance fighter Selma van de Perre and Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. Zahra Joya on her mission to "give a voice to the women of Afghanistan." Jonathan Blitzer on Trump's immigration crackdowns.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Amanpour and Company

Amanpour and Company is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Watch Amanpour and Company on PBS

PBS and WNET, in collaboration with CNN, launched Amanpour and Company in September 2018. The series features wide-ranging, in-depth conversations with global thought leaders and cultural influencers on issues impacting the world each day, from politics, business, technology and arts, to science and sports.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipHello, everyone, and welcome to Amanpour & Company.

Here's what's coming up.

On Holocaust Memorial Day, we hear stories of resistance.

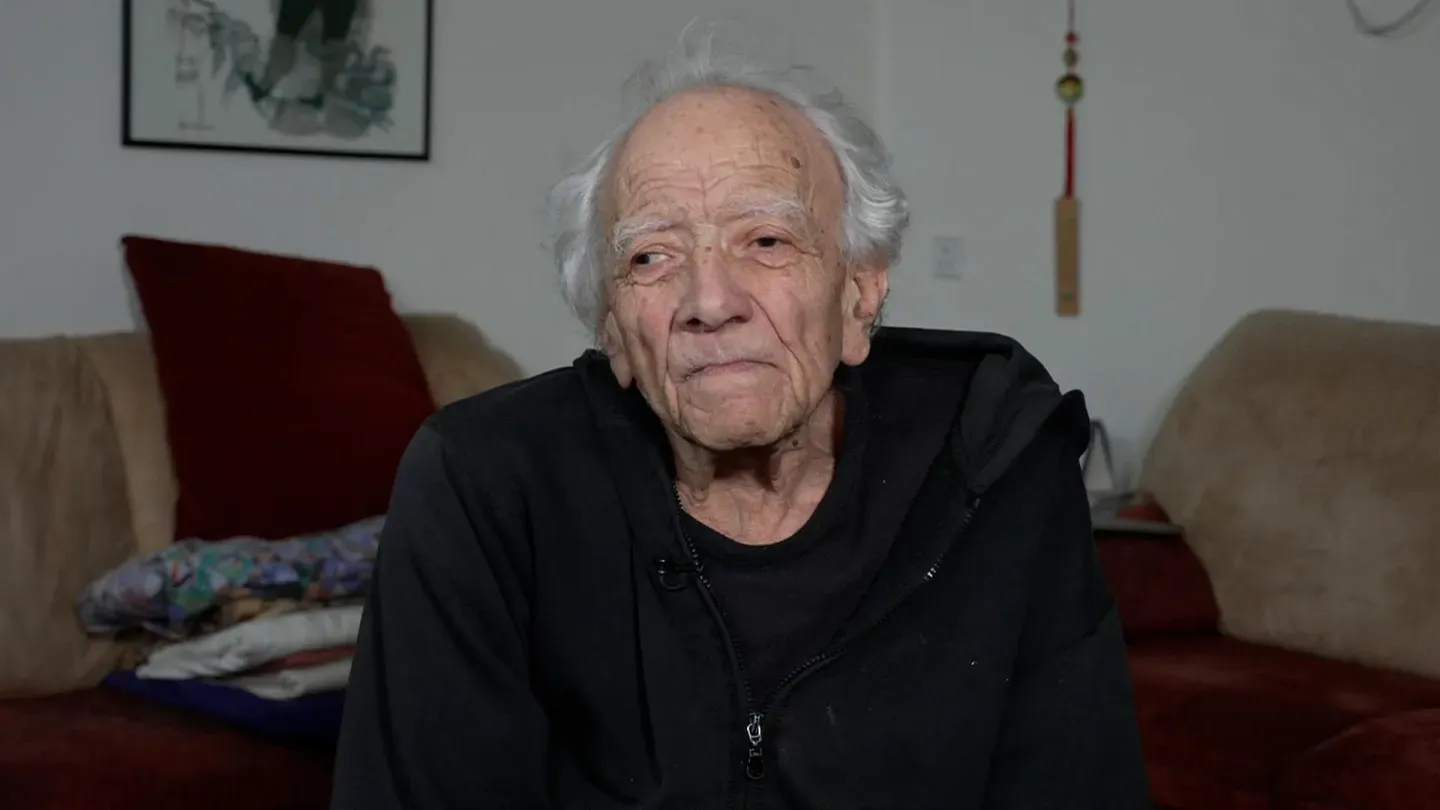

First, from double survivor Zvi Solo, who survived both the Holocaust and the October 7 Hamas attack.

Then, from our archive, Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel on the fight to prevent future atrocities.

Plus, my conversation with journalist Zahra Joya, documenting the struggle for women's rights in Afghanistan.

And Hari Sreenivasan speaks to New Yorker staff writer Jonathan Blitzer about week one of Donald Trump's immigration crackdown.

Amanpour & Company is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment Jim Attwood and Leslie Williams Candace King Weir the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Antisemitism the Family Foundation of Leila and Mickey Straus Mark J. Blechner the Filomen M. D'Agostino Foundation Seton J. Melvin the Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund Charles Rosenblum Koo and Patricia Yuen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities Barbara Hope Zuckerberg Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

A warm welcome to the program, everyone.

I'm Paula Newton in New York, sitting in for Christiane Amanpour.

Eighty years ago today, Soviet troops liberated Auschwitz, the largest of the Nazi death camps.

Now it marked the beginning of the end of the Holocaust, the murder of six million Jews alongside members of the LGBTQ community, Roma, and, of course, other targeted groups.

In 2007, Christiane visited Auschwitz for a documentary on genocide called "Scream, Bloody Murder."

Here is a reminder of the horrors that happened there and the tireless work of one man, Rafael Lemkin, to have genocide recognized as a crime, even as the Holocaust unfolded before him.

When Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Lemkin knew that his worst fears were about to come true.

Lemkin fled, leaving his country and his family behind.

I felt that we'd never see them again.

It was like going to their funerals while they were still alive.

Lemkin became one of the lucky few to reach America after a friend helped him find a job at Duke University Law School.

But he remained afraid for his family and his countrymen.

I had not stopped worrying about the people in Poland.

When would the hour of execution come?

Would this blind world only then see it, when it would be too late?

Soon the letters from home stopped coming.

The Nazis had captured his parents' village.

It was a death sentence for 40 members of Lemkin's family.

By 1942, America had entered the war, and the Germans had accelerated their deadly work.

Concentration camps ran day and night, like assembly lines.

Here at Auschwitz, more than a million people were killed.

Jews arrived packed into trains.

The Nazis sorted them on the platform, sent the doomed to the gas chambers, stripped, shaved and tattooed the rest.

Elie Wiesel was number A7713.

I was young, frightened.

The Nazis killed his mother and his younger sister.

The question of the killers has obsessed me for years and years.

How could they kill children?

I don't know.

How could they?

As Wiesel suffered in the camps, word of the slaughter reached America, but it seemed of little interest to the press and the politicians.

Raphael Lemkin was outraged.

The impression of a tremendous conspiracy of silence poisoned the air.

A double murder was taking place.

It was the murder of the truth.

Eighty years later, on this Holocaust Memorial Day, the number of survivors amongst us dwindles.

The far right is on the rise in Europe, even in Germany itself, where the AFD party held a rally this weekend with a video address from billionaire Elon Musk, as a wave of attacks on Jews and Jewish sites sweeps across the world.

Anti-Semitism spiked after the traumatic Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, and the war that followed.

This weekend, Israelis welcomed home four more hostages.

Dozens, though, still remain in Gaza, much of which is now reduced to rubble.

Some of those who survived that day in 2023 were themselves survivors of the Holocaust, including our first guest, Zvi Solow, who fled Poland, Italy and Greece as the Nazis advanced across Europe.

On October 7, Solow saw neighbors taken hostage as he held the door shut to his safe room.

He spoke with me from Southern Israel.

Zvi Solow, it is a privilege to have you on the program.

Welcome.

You're welcome, too.

You were a small child in Poland during the Second World War, and your family managed to escape in 1940.

You were just six years old, a little boy.

Can you tell us your story?

How did you manage to survive?

By luck.

My father, before the war, was a prominent lawyer in Warsaw, and he had connections.

And when Warsaw was occupied by the Nazis, we got, by his connections, permission, official permission, to go to Italy, which then was pro-Nazi, but for some reason was neutral.

So we simply got on a train and went to Trieste.

The Nazis let us out.

And we lived in Trieste for some months, and then Mussolini joined the war on the wrong side, and then we had to escape.

Then we became refugees, and we escaped to Greece, which Greece was neutral, but was protected by the British.

And we stayed in Athens for almost a year.

When Greece was about to be occupied by the Nazi army, we and everybody else who could escaped east.

And we got to what was then British Mandalay in Palestine.

That's it.

What personal lessons should we all take from your story of survival?

Well, for one thing, not to be in a position of a small, helpless minority with fascists.

Look, I was a little kid, and most of my war experience was running away and arriving in some other place and trying to adjust, and then moving again and so on.

So that's what comes to mind.

I remember.

A recent survey by the Anti-Defamation League found that half of adults, I mean, let's think about that, half of adults around the world still hold anti-Semitic beliefs and actually even deny the historical facts of the Holocaust.

According to the Jewish Agency, 2024 saw a doubling, 100% increase in anti-Semitic attacks right around the world.

That was compared to 2023.

I mean, we are seeing vandalism, serious attacks on synagogues.

Did you ever believe we could come to this point again in history?

Look, I didn't consider it very seriously, but I'm not terribly surprised because what we're seeing now are events that happened long before the Nazis came to power in Germany, all over Europe.

And so if the world got back, the Western world got back to normal after the Nazi era, they got back to normal on this issue too, unfortunately.

And what do you mean by back to normal?

Back to the situation before the Nazis came to power.

It all started from nothing.

So you believe the roots of anti-Semitism were allowed to thrive again and are to this day?

Yes, definitely.

I don't know to what extent, but I never believed it simply disappeared.

In fact, Ronald Lauder of the World Jewish Congress said, "We thought the virus of anti-Semitism was dead, but it was just in hiding," he says.

You would agree with that?

Yes.

You've been through so much, even just in the last year and a half.

On October 7th, Hamas killed 1,200 Israeli civilians and soldiers.

There were so many elderly Holocaust survivors among them who were terrorized on that day.

You yourself, you had to barricade yourself in your safe room in Kibbutz Nirim as it came under attack.

Can you tell us what happened to you on that day?

And did it bring you back to all you suffered in your childhood?

It didn't because I was too busy.

I wasn't reminiscing.

But what happens, more or less what you said, we were attacked physically.

The area where I lived was attacked.

We barricaded ourselves in our safe room.

I held the handle of the door and waited for the army to get us out for quite a few hours until they arrived.

And what was going through your mind as that was happening?

That they should arrive before the terrorists.

Where the hell are they?

According to the Israeli government, there are about 123,000 Holocaust survivors still in Israel, with over 13,000 passing away in the last year alone.

I don't have to remind you, right?

The average age of survivors is 87.

Since the war began, though, the government says that it has helped 282 survivors return to their homes.

235 from the south, 47 from the northern communities.

It bears repeating.

You were uprooted by war, having to leave the kibbutz you lived in for decades.

And again now you are displaced.

How difficult has this been for you?

It's difficult.

It's not terribly difficult because we're organized, but it's difficult, too.

My home, I asked somebody last week who was in Nirim to have a look at my place.

My place is still all right, but some of my neighbors are not.

And we don't know how long it will last.

I have no idea when I'll be able to come back.

You survived the worst of two atrocities.

How has your experience as a Holocaust survivor affected the way you feel about the aftermath of October 7?

Not much.

Not so different as I did before.

We always felt that we're on the edge of, we can't say peace, but non-war.

And it can explode any time, not any time, but it can explode this year, next year.

It did.

It wasn't a surprise.

You seem very clear-eyed about what the past held and what the future will hold.

No.

What the future will hold depends on us, too.

What we do and what we don't do.

What would you say to young people around the world who perhaps it's difficult to really press against them and really implore them to look at the Holocaust and the absolute massacre and genocide that occurred?

What would you say to young people about whether or not the Holocaust can happen again?

I'd say they should learn what happened.

And if they do, I think they'll come to the same conclusion that something like that, not necessarily exactly the same, can happen again.

And they should be very careful it does not.

And Zvi Solow, we appreciate your time today.

Thank you so much.

You're welcome.

Now, Christiane has had the privilege of speaking to many Holocaust survivors over the years, some universally recognized, all with a crucial story to tell.

Selma van de Perre was one such witness, a resistant spy who survived internment at Ravensbrück, the largest concentration camp for women.

Now, at 98 years old, Selma spoke to Christiane about her memoir of courage and strength called "My Name is Selma."

I'm going to get to the prison in a moment.

But first, I'd like to ask you to read on page 76 in your book there the passage about fear, about how, you know, fear was everywhere, but you had to put it to the back of your mind.

Well, you forget.

Yeah, you forget about fear, because I was busy as well like I was now.

When you're busy, you're able to push the things where you don't need.

You can't live in constant fear.

Even fear is something to which you become accustomed.

Quite true.

And the job, the resistance job, becomes like any other job.

Every day I did things that put my life at risk.

I didn't allow the fear to overwhelm me.

The desire to thwart the Nazis and help people in danger was stronger.

What was your experience in Ravensbrück?

Well, I've had some very horrible experiences there too, but I survived.

I wanted to...

I didn't want the Germans to have the satisfaction of killing me, of having me dead.

So I did everything to stay alive.

I was quite lucky in a way that I became the secretary of one of the chef's chiefs in Siemens factory.

I had to work in the Siemens factory.

The big German industrial... Siemens Industrie.

Yeah, which is now famous for all the kitchen stuff.

You said that to survive, you had to maintain hope.

Yeah.

So you try to do your best to survive.

It was difficult at some times.

I was beaten once unconscious when I couldn't get off the loo because my tummy was always upset, you see.

And because the food and the drinks we got was terrible or hardly anything.

When you came out, you realized eventually that your mother had not survived, your father had not, and nor had your younger sister.

Two older brothers had, and they had come here to England.

How did you reconcile?

How did you process their loss?

Well, I haven't reconciled with that at all.

I think of them every day, every night, small things happen.

And when I slice my bread in the morning for breakfast, and I half my slice of bread, I think of my mother when she butted our bread.

I can't help it.

It comes into my mind.

I try not to because I think...

I say to myself, "It doesn't make any difference.

You can't make it undone."

But I can't help it.

I think of them every day in that way.

Still thinks of them every day.

Now, Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, whom we heard earlier in the program, survived both the Auschwitz and Buchenwald camps.

He's seen here with other liberated slave laborers after the liberation.

Wiesel dedicated the rest of his life to keeping the memory of genocide alive.

Ten years ago today, on the 70th anniversary of the liberation, Christian spoke with him about his struggle to make sense of the tragedy of Auschwitz, and so many decades later.

Auschwitz really, we remember in history as a place where human beings have done to other human beings things that have never done, never should be done in history.

And of course, when I remember it, especially now in January, it was not only Auschwitz itself, but the evacuation, the march, the death march.

I was there with my father.

The last few weeks of his life were together there marching, and then the first week in Buchenwald.

But Auschwitz is a symbol of the 20th century, with all the great victories that humanity has recorded in the sciences, in literature, in philosophy.

At the same time, it's also Auschwitz.

It's a 20th century phenomenon, 20th century tragedy, 20th century crime.

But all of a sudden, in Europe, civilized Europe, of all places in Germany, which used to be the most cultured, the most elegant nation in the world in literature and philosophy for so many centuries, there we heard Hitler and his acolytes and his spokesmen preaching hatred, preaching murder, mass murder.

Mr. Wiesel?

But it happened.

Can I ask you, as you remember, can I ask you what you remember about being sent to the camp and what you remember about being there?

Well, being sent, we didn't know that.

I lived in Hungary.

Hungary used to be Romania before, then Hungary.

We didn't know about Auschwitz until we came to Auschwitz, which by the way is to me to this day a source of shock and astonishment.

We came there, of course, in 1944.

In 1944, we in Hungary didn't know that Auschwitz existed.

Had we known, believe me, had Roosevelt, had Churchill on their radio stations turned to Hungarian Jews saying, "Hungarian Jews, don't go to the train because the trains will lead you to Auschwitz."

Many of us would not have gone.

Many wouldn't have believed perhaps, but wouldn't have gone.

But nobody warned us and nobody came to our help.

It happened late in the war.

Germany had already lost the war in 1944, spring 1944.

And yet they still had enough resources and of course the will, the desire, the determination to kill the Jewish people.

To this day, I don't understand it.

It wasn't even in their own self-interest, in their own national interest.

Why did they do that?

To me, it remains a mystery.

What gave you the strength?

What was life-affirming that gave you the strength as a 15-year-old when you were sent there to keep going and to survive?

Well, in the beginning, of course, because I was together with my father.

We were in Birkenau, Auschwitz, Monowitz and then Buchenwald with my father in the beginning.

And as long as he was alive, I wanted to be alive just to keep him and help him, to share a piece of bread with him.

After he died, which was actually in late January 1945, and I was already in Buchenwald, I didn't leave.

I was in a barrack for youngsters in Buchenwald.

And believe me, I don't even remember a day of that because those three months were empty, empty, empty, just empty of anything, empty of happiness, empty of joy, empty of hope, empty of life.

Well, that was Buchenwald.

But in Auschwitz, of course, that place was a place for the first time in history, a place that was created by Germany, the German government, an army, created just to bring their people who were living and kill them, just like that, kill them.

I don't understand it to this day.

It wasn't even in their national interest what interest they had to kill millions of Jews.

But it happened.

You know, obviously, with each passing year, the number of Holocaust survivors gets smaller, gets less, and people ask, "Who's going to remember and who is going to remind?"

And I also have read so many stories of people who say they could never talk about this until they were later in life, survivors who wanted to get on with building their own life and building a new life.

What made you talk and write, and how long did it take you after liberation to be able to tell about this?

Well, it took me 10 years.

I knew I was going to write.

I had written before, but I had written about mysticism.

I was a youngster.

I was 12, 13, and I found, I went back to my hometown and found my manuscript that I had written at age 12, 13, on Jewish mysticism, of all things.

And I knew I was going to write.

But I knew one day I would have to write, and I didn't find the words.

I was afraid that I will not find them.

I'm not even sure, by the way, that I did find them.

Maybe there are no words for what happened.

Maybe somehow the Germans, which means the cruel killers, have succeeded at least in one way.

That means they deprived us, the victims, of finding the proper language of saying what they have done to us, because there are no words for it.

A profound reflection there from the late Nobel laureate and Auschwitz survivor, Elie Wiesel.

Now next, we turn to the global impact of Donald Trump's return to power.

His executive order to suspend America's refugee admissions program takes effect today, preventing thousands of people hoping to resettle from coming to the United States.

Now, many of those being left in limbo are Afghans who helped America during its war there.

It comes as the ruling Taliban, in fact, intensifies its crackdown on women's rights.

Just last week, the International Criminal Court announced it is seeking arrest warrants for Taliban leaders for gender-based crimes.

For our next guest, this is deeply personal.

Zahra Joya was forced to flee her home country when the Taliban regained control in 2021.

As the founder of Rukhshana Media, she seeks to give a voice to the women of Afghanistan.

And she joins me now from London, where she now lives.

A warm welcome to the program.

And we want to get right to President Trump's executive order now preventing Afghan refugees from reaching the U.S. And a reminder that many of those were people who helped the United States.

Are they in danger this hour because of that?

I mean, have you heard from people impacted?

Hi, good evening.

Thank you for this question.

Unfortunately, it has impacted a lot on the life of people of Afghanistan.

When they received this news about the new administration decision, I mean, many, many of them are living in limbo in Pakistan and other countries.

Of course, their life is under risk and under the danger of the Taliban, because they fleed from Afghanistan since the Taliban took power.

And they are in a very, very difficult situation at the moment.

And the third countries, whether they're in Pakistan, in Albania or Iran.

Do they feel the U.S. has abandoned them?

Do you hear that from them?

Absolutely.

Before I came to your program, I received many, many messages.

And one of them just called me and said, we need your voice.

We need your support.

And they asked if there are any possibility that we can reach out to the new government of the United States to rise our voice, to share our concern, how it is difficult for us.

And they feel betrayed, of course.

And then it is very, very hard for them to at least reach the stage.

And they flee from Afghanistan.

It was, I mean, reaching to the United States, it was the only hope left for them.

But unfortunately, at the moment, they are all in a very, very dire situation.

Among those thousands of Afghans, most of them are vulnerable people, and including the women who stood up around the Taliban.

I do want to get to one of the reasons that we're speaking to you as well, is how things have changed for - I mean, really, it's extreme, the crackdown that the Taliban has brought to women.

In many cases, they have very few rights left, countless new edicts.

We can't even enumerate them all here.

But things like banning windows from buildings where women work, they cannot speak, they cannot sing, they shall not be seen.

Can you tell us a little bit now about what women in Afghanistan are telling you?

Well, as I mentioned, the situation of women of Afghanistan is very, very dire.

And they are deprived from their most basic rights, as you mentioned.

They cannot speak aloud.

They cannot see each other from the window.

They cannot even get fresh air.

They cannot go to the park.

It is all the freedom of a human being is gone for women of Afghanistan, unfortunately.

Taliban issued more than 100 decrees to ban women from everywhere.

Basically, women in Afghanistan are facing with the dehumanization process and after the Taliban regime.

You grew up under the Taliban's first era.

In fact, you pretended to be a boy just to go to school.

How does it compare to what you went through, what's happening today?

Well, for me, I think my story is not unique.

This cycle of depriving and the cycle of violation against women are going on after more than 20 years.

So for me, of course, it was horrible.

It was a dark moment.

But there was a little bit difference because at that time, the women of Afghanistan, they couldn't stand up against the Taliban.

They couldn't rise up their voices.

They just did in secret whatever they could.

For what I did, for example, it was like a completely a secret action to get education.

I think the second time of the Taliban returned to power is different because hundreds of women, they rise up their voices, they did protest, they're asking for equality, for justice.

But unfortunately, many, many of them have been arrested.

And I mean, for me as a journalist, it's really, really hard to describe what women of Afghanistan gone through that.

The International Criminal Court now says it is seeking arrests against senior Taliban leaders for what it says are crimes against humanity, crimes against women.

This is in its own way gender-based violence.

How much of a difference do you believe those ICC arrest warrants will make for the Taliban itself?

I think this is a very good achievement for women of Afghanistan.

But of course, it is not enough as we compare the situation of the women at the moment.

It's heartbroken.

It's devastating.

But again, it gives a little bit attention from the international, globally attention because when there's news announced by prosecutor of ICC, there was lots of attention once again about the situation of women of Afghanistan.

So I mean, this is a long process.

It may take much time to the final court.

But I mean, women of Afghanistan, they are seeking international solidarity.

They are seeking for more ways.

Women of Afghanistan are asking for the international community, particularly the United Nations to recognize the Taliban as a gender-apartheid regime.

And I think we cannot wait for taking a particular action because we already lost so much time.

A circle of girls, I mean, the girls of Afghanistan, the generation of women of Afghanistan, they already get out from the circle of education, unfortunately.

Time is of the essence, as you say, because those women are suffering through that right now.

And to that point, your organization, in fact, is named after a woman who was stoned to death.

Can you describe her story to us?

It was absolutely a brutal, savage murder.

But how does it also give voice to what women are going through right now, today, in Afghanistan?

Yeah, unfortunately, as I mentioned, the Taliban, the regime, they violated the voice of the right of women many, many years.

And Rukhshana was a young girl, 19 years old, from war province in central Afghanistan.

She fleed from a forced marriage, basically.

But in 2015, the Taliban arrested her in front of hundreds of human rights organizations, many, many other countries, NATO forces.

She is stoned to death by the Taliban.

So I, as a journalist, wanted to break the silence, to just wanted to create this newsroom and named Rukhshana for her memorial.

And we just, you know, Rukhshana, maybe I can say, is a kind of mirror for women of Afghanistan, that they are reflecting themselves on that mirror, and they are seeing themselves on that mirror.

But unfortunately, it's all very, very sad news that we are publishing these stories.

But this is the only way that we can do.

You are bringing light, though, to what they're going through each and every day.

I will not forget the faces of all those young women and girls that I met when I was in Afghanistan.

But it brings about a point that I really have to ask you.

Do you feel let down by Western allies, the United States in particular?

Well, it's very difficult at the moment.

I mean, during these three years when the Taliban came, actually they brought to the power in Afghanistan, they, women of Afghanistan feel betrayed.

And they believe they, you know, the issue of the ensuring of women's rights in Afghanistan was nothing more than an empty slant, right?

So for me, I am very, I try to be optimistic, but it is very, very difficult to be, you know, hopeful.

It unfortunately is a place that you know so well in terms of wanting to be hopeful, but understanding how you need to persevere going ahead of all that is before you.

Zahra Joya, thank you so much for bringing these issues to light for us.

Appreciate it.

Now, President Trump's suspension of that refugee program is just, we were discussing one of several executive actions aimed at overhauling the U.S. immigration system.

On Sunday, in fact, Immigration and Customs Enforcement reported making more than 900 arrests right across the country as a result of the president's campaign to crack down on undocumented migrants.

He's already proving that he won't back down on his promises after Columbia announced it has agreed to all of his terms following a dispute over migrant repatriation flights.

Staff writer for The New Yorker, Jonathan Blitzer, joins Hari Sreenivasan to break it all down.

Paula, thanks.

Jonathan Blitzer, thanks so much for joining us.

You wrote a recent piece for The New Yorker titled "The Unchecked Authority of Trump's Immigration Orders."

I guess let's break down the title a little by little here.

What is the unchecked authority that you're most concerned about?

There are two general ways in which I think this latest volley of executive orders and presidential actions are unchecked.

The first is that very much built into the language and logic of these executive orders and a lot of the president's new plans is this notion that mass migration constitutes a kind of invasion.

That word is a word we've heard a lot, obviously, politically, and we at this point are almost numb to how histrionic and dramatic it sounds.

But in a legal sense, the claim being made by the new administration is that this so-called invasion necessitates a whole host of new presidential powers.

The president always has a lot of latitude and power over immigration policy, but the proposal that we're seeing in the constellation of these executive orders and a lot of the early actions of the administration suggests that they're taking the broadest possible view of what the president can do to deal with the reality of people migrating in the region.

That's the first way in which this kind of new set of powers are unchecked.

And the other, I think, is a political issue, which is, you know, we're in a moment where the general consensus seems to be, and I don't think it's as clear as the consensus suggests, that the president has a popular mandate to pursue a lot of his immigration policies.

Immigration policy is extraordinarily complex.

I'm not convinced that the public always understands different facets of what immigration policy looks like or, for that matter, the impact it has on people living in the U.S. And so my big concern, too, the same day, the first day in which President Trump takes office, that you have all these executive orders coming out of the White House, you also had in the Senate 12 Democrats joining Republicans to pass what's called the Lake and Riley Act, which is a draconian and very, very extreme bit of enforcement policy, which suggests to me the fact that Democrats right now are very much cowering from the kind of political threat that Trump seems to represent on this issue.

So my concern, too, is that we're entering a moment of, you know, very wild and radical policymaking from the White House when there seems to be a real scarcity of political impediments to his pursuit of those powers.

Okay, let's take that down one step at a time here.

We'll get to the Lake and Riley Act, but first, what is the value or the I guess the worth in giving something a name, calling it an invasion or as one of the other executive orders did, calling out cartels and calling them foreign terrorist organizations?

So there are kind of two things you see in these executive orders.

The first is something that we have seen President Trump do before in his first term, which is to declare a national emergency at the southern border.

And factually, I think that is wildly off.

And we're at a moment when the number of arrivals at the southern border are way down.

In fact, the situation is very much under control.

That's not to say the system doesn't need reform and repair.

But the idea, even that the president is saying there's an emergency and he's sending federal troops through the Pentagon to the border to assist DHS, the Department of Homeland Security and law enforcement, that already, to my mind, is a real misconstrual of what the reality is on the ground.

But to your question, the utility for the new administration of calling mass migration and invasion is that it allows the president, by the logic of these executive orders, now, obviously, this is an unsettled legal matter, and there will be all kinds of challenges in the courts.

But by the logic of these orders, the idea is that because the arrival of so many people constitutes an invasion, the president has authorities that go over and above authorities laid out in the immigration statutes that regulate and direct immigration policy and that go to questions that are constitutional.

That the president, as commander in chief, has a responsibility to repel invasions, to defend the territorial sovereignty of the United States.

Once we enter that territory, the scale of what the U.S. military can be brought in to do expands considerably.

Now, we're in entirely uncharted territory here, so I don't know what this would all look like concretely, but studied through these executive orders are references to extremely rare and alarming historical acts, like the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 and the Insurrection Act, that basically forecast that the president is willing to go to great, great lengths to use the military to start carrying out enforcement operations at the border and in the interior of the country.

We'll have to see whether or not this materializes, but that's at least the logic as laid out in some of these orders.

The Alien Enemies Act or the Insurrection Act that some of these reference, these were in incredibly different times in America, right?

But at the same time, the president, even in his first term, was able to mobilize U.S. troops to go to the southern border.

And we hear now that the Pentagon is going to dispatch about another 1,500 people to the border as of just this past week.

Yeah, and I should say, the fact that troops are being sent to the border to work in partnership with the Department of Homeland Security, that is something that has happened before, not only under Trump in his first term, but under Democrats as well.

So that on its own isn't something kind of out of left field, say, in the history of U.S. policymaking in regards to the border.

Generally, though, there has been more of a specific justification for sending those troops at a given moment in time.

Right now, for instance, there aren't huge numbers of people arriving.

It's not fair or accurate to say that federal immigration authorities are overwhelmed at the southern border.

So it's, of course, extremely dubious to be staging this bit of political theater with troops being sent to the border.

But the fact of sending troops, troops, the Department of Defense have actually always had a role to play in immigration management at the border, whether it's to provide provisional detention centers for newly arrived migrants, whether it's to help with monitoring or logistical tasks along the border.

That sort of thing on its own isn't wildly unprecedented.

What is, is the language in these executive orders suggesting that the scale of what the U.S. is facing, the so-called invasion, necessitates a whole higher order military intervention.

That, to me, is a major departure and a major escalation, the likes of which we've really never seen.

One of the executive orders about birthright citizenship challenging the 14th Amendment has already been constitutionally challenged.

There was a federal judge that on Thursday blocked it, saying it was, quote, blatantly unconstitutional.

So I guess, why even take that step?

What is behind trying to draft an executive order that not only do you know is going to be challenged, but very likely will get blocked in court?

That's a good question.

I think built into the new administration's plans, and this I've gotten from, you know, the president's advisors and, you know, allies of the presidents over the years, is this idea that if they flood the zone, you know, day one, if they accomplish as one of the, as one presidential advisor had told me in the past, you know, the idea is to accomplish in 100 hours what used to be accomplished in 100 days.

The thinking being, if we overwhelm all of the opposition, opposition from Democrats, opposition from civil society groups, resistance from the public, we can achieve more because it's hard for our political opponents to know even where to start.

That said, the idea that that birthright citizenship executive order would come out as starkly and immediately as it did is, I think, also reflective of the fact that they're ready and willing to fight this thing out in the courts.

And I would say a kind of ancillary political benefit for them in these kinds of protracted legal battles is the fact that the public gets desensitized to some of the terms under discussion.

Jonathan, that reminds me, there were already reports that in Newark, New Jersey, there were ICE raids on a specific business.

I know Senator Booker and the mayor, Barack, have been pushing back about this and want more information on exactly what happened.

There seems to be a gap here between what is laid out as an executive order on day one, whether we have to wait for the courts to have injunctions and to stop things, versus like the memo that gets written to the local ICE office that says, you can do this now.

In the past, the way ICE conducts its operations is it prioritizes people for arrest.

There are so many undocumented people living in the United States that it's impossible for a law enforcement body to attempt to arrest all of them unless there are some guiding principles for how they go about that work.

And so what's happened over the years is ICE as an agency has refined a set of priorities whereby it essentially targets for arrest and eventual deportation people who have committed serious crimes and people who have arrived very recently in the country and are undocumented and maybe have orders of removal.

And what that's meant for people who don't fall into those particular categories is, by and large, they don't have to worry about the kind of randomness of just getting swept up any particular day because of their legal status.

That is all out the window.

And a lot of checks on how ICE arrests occurred in the past are also out the window.

For instance, for years, there was a kind of general idea laid out in the regulation of ICE that, OK, you wouldn't make arrests at schools, at hospitals, at places of worship.

It's called the sensitive locations policy.

That policy has been scrapped.

And so the idea now really is it is a free-for-all in a way that it hasn't been for the last four years.

And we're going to see flare-ups all over the country, and I think particularly in Democratic enclaves, because there are, A, large immigrant populations in a lot of big metropolitan areas in the United States, and, B, because those cities represent, to the president and his party, political opposition.

Are we heading to a scenario here where the federal government tries to prosecute state and local jurisdictions and individuals?

And how does that tension get resolved?

One of the striking things with the sanctuary jurisdictions and so on is the politics in these places has also started to really shift over the last couple of years.

And so there was a lot more outright resistance to the Trump administration in 2017, during that first term, than there is now.

And some of this is the result of the governor of Texas' Greg Abbott's busing plan, which began basically in the spring of 2022.

And he bused more than 100,000 recently arrived migrants from Texas to blue cities and states across the country without coordinating with local authorities ahead of time, and very much overwhelming city and state resources.

And so as a result, in a lot of these cities - I mean, I'm speaking to you from New York - the politics in New York City itself and in the suburbs of New York City and in the state at large have really shifted.

And so, you know, there's - over and above the legal questions they're flagging, there's also this question of political will.

You know, if there is sustained and serious pressure from the current administration brought to bear on, you know, cities and states that typically have held the line against these kinds of federal incursions, you know, do local officeholders or state officeholders really want to duke it out at a time when it seems like, by and large, the public's hostility to immigration on the whole has really grown.

You mentioned earlier the Lake and Riley Act.

For people who aren't aware of it, what is the significance of it that just passed the Senate?

The Lake and Riley Act essentially does two things.

First, it requires the detention of any undocumented immigrant who is charged of even minor crimes, like shoplifting, for instance.

Which is to say, you do not have to be convicted of these crimes.

Merely charged to trigger the mandatory detention and what almost always follows in the case of undocumented immigrants in these instances, deportation.

And then the second prong of this law, which in many ways is equally radical, is the idea that it allows state attorneys general to sue the U.S. Attorney General or the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.

If someone who has been paroled into the country just means that someone is given legal protection to enter the country.

It's not a permanent status, but it is a kind of an official way of bringing someone into the country.

If a person paroled into the country goes on to commit any sort of crime or cause any kind of damage, whether it is to a person or to the finances of a person or the state, in an amount more than $100.

I mean, this is extraordinarily draconian.

And the fact that Democrats immediately got on board with it and didn't really even put up much of a fight or push in a serious way for amendments or carve outs, really reflects their desperation to try to outrun this immigration issue, which they feel has really dogged their party, in which the President has clearly used his advantage.

Now, we've been talking a lot about immigrants coming across the southern border, but there are obviously asylum seekers, there are refugees.

And those programs in the United States have already also been affected by the incoming administration.

We saw the app that a lot of people, asylum seekers, might be using at the southern border.

And we also have heard reports about refugees, including about, what, 1,500, 1,600 Afghans who the United States has said, "We'll take care of you."

They are now kind of in limbo, too.

What's going on?

So the U.S. refugee program, which Trump essentially decimated in his first term, got restored in large part by the Biden administration.

And now it has been frozen in place again by the Trump administration in the form of this executive order, which basically said anyone at any stage in the refugee resettlement process is now on hold.

And so you have 10,000 people who have already been vetted, whose security background checks have already been run, who are literally just waiting for airfare to come to the United States and be resettled are now stuck with no obvious path forward for them.

So that's one prong of all of this.

And then, as you mentioned, at the southern border, the Biden administration really cracked down on asylum in between ports of entry.

So if people were to show up at the southern border seeking asylum, the Biden administration was very harsh with them if people showed up in between ports of entry.

But what the Biden administration did simultaneously was it said, OK, every day at ports of entry, there are appointments for 1,400 people a day to be paroled into the country.

And that way, they can begin any sort of legal process they want to pursue.

The current administration in its executive orders has also immediately halted the app that allowed for those applications and scheduling to start.

And an additional program that the Biden administration had put in place, allowing for 30,000 migrants from four countries where there have been high rates of immigration over the last few years, that also got frozen in place.

And so now there are large numbers of people who, by and large, were trying to avail themselves of specific legal channels created by the previous administration or already existing in U.S. law, who are now completely frozen out of the system.

Jonathan, you've been covering this topic for quite some time.

You even wrote a whole book about it, Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here.

And I wonder, put this in perspective for us.

Given that even in the length of time that you've been following immigration, how significant are the changes that we're seeing really just in the past week?

And compare that to what's been happening, our immigration policy that seems to ebb and flow from one administration to the next.

You know, a lot of the stuff you're hearing about, a lot of the stuff you're seeing, whether in the form of executive orders or whether in the form of this new legislation, are not addressing particularly acute needs that experts say are things that need to be addressed to improve the immigration system.

And so the political conversation, I guess, when I take this kind of broader view, as you can imagine, politics around immigration have always been intense.

They've always flared up over time.

But we are in a moment where the politics have veered off so drastically from any of the actual policy discussions of what needs to happen or what should happen, that I think there's a level of dysfunction that's new.

Jonathan Blitzer, author of Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here and staff writer of The New Yorker, thanks so much.

Thanks for having me.

Now on this important day of remembrance, a final thought.

As years pass and understanding of the Holocaust unfortunately diminishes, it is vital to continue listening to the firsthand accounts from the survivors themselves to the journalists who bore witness.

The BBC's Richard Dimbleby was the first reporter to enter the liberated Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Here's part of the radio report he filed on the horrors he saw.

I find it hard to describe adequately the horrible things that I've seen and heard.

But here, unadorned, are the facts.

I passed through the barrier and found myself in the world of a nightmare.

Dead bodies, some of them in decay, lay strewn about the road and along the rutted tracks.

On each side of the road were brown wooden huts.

There were faces at the windows, the bony, emaciated faces of starving women, too weak to come outside, propping themselves against the glass to see the daylight before they died.

And they were dying every hour and every minute.

And that's it for our program tonight.

If you want to find out what's coming up on the show each night, sign up for our newsletter at pbs.org/amanpour.

Thank you for watching Amanpour & Company.

Join us again tomorrow night.

Support for PBS provided by: