The Battle to Beat Malaria

Season 50 Episode 17 | 53m 54sVideo has Audio Description

Follow the quest to create a lifesaving malaria vaccine.

Are scientists on the verge of a breakthrough in the fight against malaria, one of humanity’s oldest and most devastating plagues? Follow researchers as they develop and test a promising new vaccine on a quest to save millions of lives.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Viking Cruises. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting , and PBS viewers.

The Battle to Beat Malaria

Season 50 Episode 17 | 53m 54sVideo has Audio Description

Are scientists on the verge of a breakthrough in the fight against malaria, one of humanity’s oldest and most devastating plagues? Follow researchers as they develop and test a promising new vaccine on a quest to save millions of lives.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: This tiny creature is at the center of one of medical science's greatest quests... A battle to save millions of lives and end a scourge that has shaped human history: malaria.

One child dies every single minute from malaria.

So you might ask yourself, "Why are kids still dying?"

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: For almost a century, scientists have had one goal.

We don't want to use the word "the Holy Grail," but if we got vaccines, then, of course, that would be transformational.

KATIE EWER: The chances of success are really, really small.

But the rewards, if you do it, are enormous.

NARRATOR: This is the inside story, across four continents, of a new vaccine against malaria and the struggle to make it succeed against the odds.

The field of malaria vaccine research is littered with failure.

ADRIAN HILL: It didn't work, it didn't work, and it didn't work.

UMESH SHALIGRAM: I remember very openly and straight telling that this is not going to work.

And after many tweaks and changes, it did.

Well, to me, it was unthinkable before it happened.

♪ ♪ This could be a gamechanger.

You are touching human life.

You are going to save the human life.

It's not one or two, it's millions of lives.

Amazing.

NARRATOR: "The Battle To Beat Malaria," right now, on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: Major funding for "NOVA" is provided by the following: ♪ ♪ TIMOTHY WINEGARD: Throughout our history, the mosquito has been the paramount killer of humanity.

If we look at our Neverland nightmares, we're taught to fear all these other creatures because they kill so many humans.

That's just simply not true.

For example, wolves and sharks kill only about ten people per year.

Whereas the mosquito, this tiny little animal the size and weight of a grape seed, is responsible for up to a million deaths a year.

But it's not the mosquito itself.

It's the pathogens that hitch a free ride that cause so much suffering, death, and destruction.

And of all the pathogens that mosquitoes carry, by far the most lethal and the biggest killer of humanity has been malaria.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: A highly effective vaccine against malaria would be a historic breakthrough.

And getting there starts with knowing your enemy.

London's Natural History Museum is home to one of the world's greatest collections of insects.

Senior curator Erica McAlister looks after 150,000 specimens, representing 2,900 species of mosquito.

We have maybe 350 drawers of mosquitoes, but only 20 of those drawers are the species of mosquitoes that are important for the transmission of malaria.

The difference between the males and the females is very important.

The males are all vegetarian, but the female has to generate the eggs.

Therefore, she needs a really, really high-protein meal: the blood.

We've got the proboscis, her fantastically long mouthparts.

It's composed of six stylets.

She uses two of those to kind of, like, penetrate the flesh, she uses two of them to keep it open, and then her final two, one is basically a tube, which she will suck up your blood with.

But the other one, through that, she releases her saliva to prevent the blood clotting.

And it is in that process that the malaria parasite is able to transfer into us.

♪ ♪ FILM NARRATOR: Public enemy number one: anopheles, the malaria mosquito, wanted for bringing sickness and misery to untold millions.

NARRATOR: Today, malaria is considered a tropical disease, but until very recently, it affected people worldwide.

And it's played a huge part in our history.

WINEGARD: The United States, for example, was awash with malaria, in particular across the South, and even parts of the Eastern seaboard.

♪ ♪ The American Revolution was decided by malaria, with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

He surrenders because he only has 35% of his troops left on account of, the ague is what the British called malaria at the time.

Eight U.S. presidents contracted malaria.

George Washington was one of them.

He was bled, which was one of the crazy cures at the time.

(girl crying) He had his first bout at age 17, and had repeat infection throughout his life.

At the dawn of the 20th century, a physician of tropical medicine remarked that the future of humanity would be decided by one battle: man versus mosquito.

FILM NARRATOR: All right, men, now we can begin to fight.

("Assembly" bugle call playing) (clangs) NARRATOR: During World War II, military casualties from malaria were so high that the authorities declared total war, even recruiting Walt Disney for the fight.

FILM NARRATOR: Attaboy, Dopey, kill her good and dead!

NARRATOR: The newly invented insecticide DDT destroyed mosquito populations.

Swamps were drained.

Protection against bites improved.

As did the availability of malaria treatments and tests.

WINEGARD: In the Western world, malaria was made extinct, essentially.

America was declared malaria-free in 1951.

As a result, the malaria burden shifted to the lower socioeconomic countries, specifically in the global South.

Funding for malaria research was drastically cut, and malaria was generally all but forgotten in most wealthy nations.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Nine out of ten people in Tanzania, East Africa, live in the country's malaria zone.

♪ ♪ And it's the youngest children, naturally much less able to fight off infections, who are most at risk.

Farhiya Salum is three years old.

She lives in Kiwangwa village with her mother, Zuhura Abasi, a pineapple farmer and small trader, and her grandmother Huba Mohamedi.

ABASI (translated): Farhiya has been sick with malaria quite a few times.

She gets a really high fever.

Her whole body is so hot.

It gets particularly bad at night.

It's so scary that a single mosquito can pass on malaria and potentially kill someone.

MOHAMEDI (translated): Growing up, we weren't aware of malaria as a disease.

When I was ill, I would be given roots and herbs.

That's how it was back then.

Three of my children died.

I'm now left with six.

This is the area where we buried my children.

On one occasion, I went to the fields with a healthy child.

A fever came on suddenly there.

And by the time we got home and my mother attended to him, he was gone.

Every time I come here, it's so painful.

Malaria is such a bad disease.

Bad, so bad.

NARRATOR: Across Tanzania and much of Africa, malaria costs lives and livelihoods, undermining the potential of an entire continent.

Dr.

Ally Olotu, of the Ifakara Health Institute, serves on the medical frontline.

(people talking in background) OLOTU: I got malaria when I was young, and I also got malaria when I went to the university.

That's when I became aware that this is a, it's an awful disease.

(people talking in background) OLOTU: Globally, malaria causes over 200 million cases and more than 600,000 deaths annually.

About 80% of these deaths are actually young children below the ages of five.

♪ ♪ OLOTU (speaking Swahili): MAMA TAWAKAR: OLOTU: NARRATOR: Tawakar is three years old, and was in grave danger of falling into a coma until he came to the hospital just 24 hours ago.

OLOTU: Seeing kids who are suffering from malaria, emotionally, it's always difficult.

As a clinician, as a father, I have to develop interventions to do everything possible to get rid of malaria.

(speaking Swahili): NURSE: OLOTU AND NURSE: OLOTU: NARRATOR: While Ally regularly treats children who have been infected, his colleague, mosquito biologist Fredros Okumu, works on malaria prevention.

Hey, how are you doing?

How are the mosquitoes today?

Have you blood fed the mosquitoes?

Uh-huh.

To evaluate specific products for protecting people, we have to rear the mosquitoes in our labs.

(mosquitoes buzzing) We have to provide water, sugar, and blood.

NARRATOR: Today it is lab technician Steward Ng'ala's turn to feed the mosquitoes.

STEWARD NG'ALA (translated): I don't need to be brave.

It's normal; nothing to be afraid of.

It's not painful; just a bit itchy.

♪ ♪ OKUMU: The mosquitoes we have in the lab are malaria-free.

It's something that we scientists do, so...

I mean, I do it as well.

(mosquitoes buzzing) (zipping) NARRATOR: Fredros uses these mosquitoes to test insecticide-treated bed nets.

It's estimated that over the last 20 years, tools like these have prevented a staggering two billion cases of malaria and nearly 12 million deaths.

Yes, there's been extensive progress.

Is it sufficient progress?

No.

Because now we have this challenge since around 2015, where there are many countries in Africa where malaria cases are going up.

♪ ♪ There's not much killing of mosquitoes.

So that particular net didn't kill enough mosquitoes, okay.

The bed nets that we have in the villages are starting to face a lot challenges.

Mosquitoes are no longer being killed as effectively because they have become resistant to the insecticides that we put on the surface.

And so the bed net can lose that quality, the killing effect.

NARRATOR: Despite concerns about increasing resistance, bed nets treated with insecticide remain the world's number one weapon against malaria.

But research shows they reduce child deaths by less than 20 percent.

We need a transformational tool, and I do not think there is any medical intervention that has done better or more than vaccines.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: When it comes to transforming human health and saving lives, vaccination is up there with clean water and sanitation.

Smallpox, which killed up to 500 million in the 20th century alone, was eradicated in the 1970s thanks to vaccination.

And there's also been huge success against polio, measles, and recently COVID-19.

But a highly effective malaria vaccine has never emerged.

That's not for lack of trying.

Ally himself has worked on multiple vaccine candidates.

OLOTU: So do you know what Daddy is working on?

What am I working on?

Malaria.

Malaria what?

Malaria vaccine.

Okay.

So that you can, you can protect children isn't it, from getting malaria?

IRFAAN OLOTU: Because children below, under five years who have malaria are in much bigger danger than others.

And they die?

Yes, they can die.

But if you go to hospital fast, you survive.

I saw a child, three years old, who had malaria in the hospital.

But he was treated and he will get better, but he was very lucky.

As night falls, this is the most vulnerable time.

That's when the mosquitoes come in.

When the mosquito bites, it inject into that child small parasites.

We call them sporozoites.

These spend a very few minutes in the blood.

And then quickly go and start to multiply within the liver.

♪ ♪ And these kids could be playing around.

They could be playing football, they could be singing with their parents.

(children laughing) Nobody can suspect anything.

But from the liver, within a few days you could have thousands and thousands of parasites released into the blood.

They attack our red blood cells, destroying them.

And this is what actually give rise to malaria symptoms.

That child you saw playing with his friends just a few days ago can quickly become severely sick.

And if not diagnosed and treated very fast, that child might lose life.

NARRATOR: It's this process, the way the body is overwhelmed before it has a chance to fight back, that makes malaria so dangerous, and the development of a vaccine so challenging.

We have developed vaccines for other diseases, of course, but most of these are viruses and bacteria, which are much simpler pathogens compared to malaria.

It's a very complex parasite.

So I was really excited to be part of the consortium of scientists put together by the University of Oxford to work on a new malaria vaccine.

NARRATOR: The University of Oxford is home to one of the world's largest academic vaccine development programs.

In 2020, the university's Jenner Institute created the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, and since then, three billion doses have reached 170 countries.

♪ ♪ Adrian Hill and his colleagues have found malaria much more difficult.

HILL: We've known for over a hundred years that it would be fantastic to have a malaria vaccine.

People have been trying for about 120 years, ever since the parasite was discovered.

I did a count about six months ago of how many vaccines had been made and gone into clinical trials for malaria, how many different ones.

And that number was 142.

I'm not sure there's another disease where they've been that many vaccines that didn't work.

(indistinct chatter) KATIE EWER: But don't you finish at quarter past 12?

NARRATOR: Katie Ewer is the lead immunologist on the Oxford team.

EWER: I think malaria is more personal for me because it's children.

I think you'd have to be a very hard-hearted person not to be moved by a death toll of 400,000 kids a year dying in Africa, under the age of five, from malaria.

It's a huge motivator to work on something where the chances of success are really, really small.

But the rewards, if you do it, are enormous.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: For the last 13 years, the Oxford team has been working on a vaccine called R21.

Its goal is to fire up the body's immune defenses, to be ready to attack the parasite at its most vulnerable moment; just after it enters our blood.

When an infected female mosquito takes a bite and injects sporozoites, malaria parasites, there's about a half-hour to two-hour window before the parasites invade the cells in your body and set up infection there.

And that's the window that we're trying to target with our vaccine.

NARRATOR: What the R21 vaccine must do is mobilize an army of antibodies.

The problem has been to produce enough antibodies to clear all of those parasites very quickly.

When people are infected with malaria, they make antibodies in the blood that stick to the outside of the parasite.

They're meant to stop it in its tracks before they can reach the liver.

But in a natural infection, there just aren't enough antibodies.

NARRATOR: Threatened by just a few invading parasites, our antibody response is usually too little, too late.

But luckily, the malaria sporozoite has an Achilles heel.

To invade the liver, it relies on a coating called CSP, the circumsporozoite protein.

HILL: What we need are large amounts of very specific antibodies that bind as tightly as possible to the circumsporozoite protein.

Then we should be able to stop the parasites.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: This is where the R21 vaccine comes in.

It is built from the CSP protein, and so induces the body to produce an army of antibodies tailor-made and ready to neutralize the parasite.

But this is not a new idea.

First designed in 1987, a vaccine called RTS,S already does this.

I have had the privilege to work on RTS,S malaria vaccine.

And the overall efficacy of RTS,S is about 40 percent against clinical disease.

40 percent may sound as not very good efficacy, but you have to think about the burden of malaria.

We have well over 600,000 deaths annually.

(cheers and applause) NARRATOR: After lengthy deliberations, in 2022 RTS,S became the first malaria vaccine approved by the W.H.O., the World Health Organization, 35 years after it was initially developed.

But RTS,S is expensive to produce, supply is currently limited, and it falls short of the W.H.O.

's own target of having a 75 percent effective vaccine, by 2030.

And so the Oxford team had long set their sights on an upgrade.

R21 was born out of the idea that perhaps we could make a slightly better version of RTS,S.

So it started with a PhD student called Kat Collins taking this on as her project.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The RTS,S vaccine is made of billions of tiny particles.

They're built from a virus protein that forms a harmless, empty shell, and part of the same CSP protein that coats the malaria parasite.

Together, they trigger the body's immune response, but unlike the malaria parasite, less than a quarter of each particle's surface is CSP.

Kat Collins and her Oxford colleagues wondered, could increasing the amount of CSP, to better mimic the malaria parasite, make a better vaccine?

We kept on trying different ways to get that to form into a particle.

And it didn't work, it didn't work, and it didn't work.

And, eventually, after many tweaks and changes, it did.

That was a big day.

You can literally see these particles with an electron microscope.

And, boy, those images are memorable.

And we thought, "Fantastic, we immunized mice."

And guess what?

They were nearly all protected very well.

This was 2012.

We were finally getting there.

And, of course, getting there means you're ready to try and manufacture and go into the clinic.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Oxford University's R21 was doing exactly as they'd hoped, creating a strong protective immune response.

But that was just in mice.

The big challenge now would be testing it in humans.

For this, they called on Eleanor Berrie, a specialist in vaccine manufacture for human trials.

Vaccines are actually one of the most complicated things you can manufacture.

But Adrian and Kat were so enthusiastic about R21, they had generated some excellent pre-clinical data, and that enthusiasm rubs off on you.

So, you know, you begin to feel, well, we could do this, yeah.

NARRATOR: Eleanor and her team only needed to make enough R21 to inject a small number of healthy people.

Less than half a cup's worth, but thousands of times more than Adrian's team had created in the lab for their mouse tests.

And this time, with human safety on the line.

BERRIE: We started the project in 2012, and it took us three-and-a-half years.

If we had been in a commercial situation, I would have think that they would have just stopped the project on many occasions.

We kept going and kept spending, and find... finding and spending more money to get it manufactured.

The major feeling was just a sense of relief that we had got there.

HILL: The 10th of November 2015.

85 vials certified.

Three doses per person, 20 to 30 people that would cover.

Not exactly vaccinating the world, is it?

But it's where we started.

NARRATOR: With these precious few doses of R21, the Oxford team began small-scale human trials.

First, they mixed the vaccine with a substance called Matrix-M, which helps strengthen the immune response.

They injected 28 healthy adults, and reported it induced an antibody response comparable to RTS,S at a much lower vaccine dose.

Next, they purposely exposed a few vaccinated people to infectious mosquitoes, in what's known as a malaria challenge trial, and found that they were protected from malaria.

Such exciting early results drew attention beyond Oxford.

HILL: Word got around, and we academics talk at meetings and you never know who's in the room, but my guess is there was somebody from the Serum Institute of India.

And the next month, Umesh Shaligram turned up here wanting to talk about malaria.

Certainly, Oxford data was very convincing early data.

So that certainly made a big difference in our conviction.

HILL: They'd heard about the initial challenge results.

They came to us.

Normally, we go begging to companies, asking them to work with us.

We made a kind of a handshake deal that we could manufacture the product.

That's how the whole thing started.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The Serum Institute of India is the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world.

Two-thirds of all babies born globally get at least one of Serum's childhood vaccines, made here in Pune.

It's made this family-run company a global life-saver and CEO Adar Poonawalla a multi-billionaire.

ADAR POONAWALLA: Every time we look at a vaccine, the way we look at it is that unless we can make hundreds of millions of doses for the whole world, and unless it has that need and demand, we don't get into it.

Ah... Baitho.

What's happening?

(voiceover): These are very large populations, so they need a lot of vaccines.

It'd be unimaginable if they had to pay $10, $20 for a vaccine.

They wouldn't be able to afford it.

We charge pennies on the dollar for the vaccine.

But the economies of scale that we operate at enable us to do that and still make a modest profit.

You can go ahead with that.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In 2017, Serum took over manufacturing R21, and spent two years developing a new, reliable method to produce it at scale.

The team chose the West African country Burkina Faso, where around half the population gets malaria each year, for the vaccine's first real-world test.

In 2019, 450 very young children, the group most in need of protection, were vaccinated in a Phase Two trial.

For success, these babies would have to experience no unexpected side effects and there would need to be a significant reduction in malaria cases in those who received R21.

♪ ♪ The UK team waited for news.

It was actually my colleague Mehreen who said, "Look at your email, we've got the results."

77 percent efficacy, as good as we could possibly have hoped.

I wasn't even sure that I could quite believe what I was reading.

You know, we showed that the vaccine, albeit just over six months, had worked in the target population, in the target age group.

But if you've seen really good results, you know what's coming-- large scale, Phase Three trials.

Definitely a very daunting prospect.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Phase Three is the largest clinical trial.

It will need to be big enough to determine if R21 can safely prevent malaria in thousands of children.

And this will cost around $20 million.

Me and Adrian went almost every door to door and tried to search for the funding.

Somebody should support us.

And we had really a tough time.

HILL: We're fighting for funding against people dealing with other very important medical diseases.

People are more likely to try and invest in something that sounds new than the old idea of making a vaccine against malaria, which has failed and failed and failed over decades.

SHALIGRAM: After a year's try, I remember I said, "Mr. Poonawalla, sir, "I'm having a big challenge of getting the funding for the Phase Three."

And he said, "No, no, don't worry, "malaria is very close to my heart and I want to support the Phase Three."

NARRATOR: The Serum Institute CEO agrees to fund the trial.

The results had demonstrated that the vaccine is giving you protection.

So instead of wasting time, we just wanted to get on with the work.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In April 2021, Phase Three trial preparations begin in Burkina Faso, Mali, Kenya, and here in Tanzania.

♪ ♪ Mehreen Datoo is a British infectious disease doctor.

But her key role on the R21 team is to oversee its ultimate test.

(people greeting each other) DATOO: What we wanted to propose today to do is a mockup vaccine preparation for us, just to check it's all running smoothly.

NARRATOR: Nearly 5,000 very young children are set to receive shots in the Phase Three trial, hundreds of them in Tanzania.

For every two children that receive R21, one child will receive a control vaccine.

In this case, a vaccine against rabies.

This should look just like R21, but offer no protection at all from malaria.

The rabies vaccine is a good option because it's not a vaccine that children would normally receive in that part of the world, so it does provide some benefits.

NARRATOR: Crucially, Mehreen and almost everyone involved is blind to which vaccine each child receives.

So they must monitor cases of malaria across the whole trial, and only learn much later if those cases were in the R21 vaccine or the control group.

The only people that are unblinded are the pharmacy team who prepare the vaccine.

You want to make sure the whole volume is covered.

(voiceover): The whole idea of this is to not know which vaccine the child has received to ensure there's no bias.

It means that, you know, we will get the most accurate data.

That's why there's two of you to do it.

♪ ♪ (indistinct chatter) My family are actually from East Africa.

Unfortunately, when I was doing some research there previously, I got malaria and I was very, very sick.

I basically fainted and collapsed.

And then was diagnosed with severe malaria.

I don't remember a lot of it because I was just very, very unwell.

I was in my early 20s, so I can't even imagine how it affects very young children.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Here in Tanzania, Dr.

Ally Olotu is managing the vaccination and monitoring of 600 children.

OLOTU (speaking Swahili): WOMAN (speaking Swahili): OLOTU: ZUHURA: OLOTU: Farhiya!

Okay.

WOMAN: Irene.

OLOTU: NARRATOR: In late 2022, a precious cargo arrives at the Kiwangwa clinic, from India.

After an initial three doses of either R21 or the rabies control vaccine, a one-year booster shot is now being prepared for Farhiya and the other trial participants.

ZUHURA (translated): I enrolled my child Farhiya in the program above all because they have great services and really take good care of a sick child.

And they also have all the tests, so that was an incentive for me.

I'm really excited Farhiya is one of the first to get vaccinated.

NARRATOR: For Zuhura, vaccination is about much more than simply preventing her daughter from falling ill. ZUHURA (translated): We are a generation of strong women.

My mother fought hard for us, and she's still working hard despite her age.

We're busy farming as well as running a small business selling bhajia and mandazi.

Our livelihood depends on my small business, and when Farhiya falls sick, I can't attend to it.

And when you take her to the local clinic in Kiwangwa, they won't treat you without either medical insurance or $5,000 in cash.

(speaking Swahili, laughing) HUBA MOHAMEDI (translated): Instead of spending money to treat malaria, whether for kids or adults, you can buy food, vegetables, and the like instead.

We'll be very grateful for the vaccine.

(people chattering, child cooing) NARRATOR: For families and scientists alike, vaccination day is special.

They all look relatively happy.

No one's crying!

They do.

Yeah, yep, absolutely.

DATOO: It's really nice to see the relationships the trial team have with the participants and the caregivers, because I think that makes it, you know, almost a bit more like family.

♪ ♪ MOHAMEDI (translated): Farhiya being in the vaccination trial gives me joy.

She will set an example for others.

(indistinct chatter, child whimpering) (cheers, applause) NARRATOR: After vaccination, Farhiya and the other children in the trial are closely monitored for signs of malaria.

The vaccine's success or failure will depend on how many malaria cases occur in children who received R21 versus the control vaccine.

While they wait for this result, the team is also investigating what the vaccine is doing inside the body.

(baby crying) For that, they have to study the children's blood.

OLOTU: We can now measure the amount of antibodies that are in the blood.

Some of this will be shipped into a reference lab in Oxford, where samples from other sites which are participating will be analyzed.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: As Phase Three booster vaccinations proceed, immunologist Katie Ewer and her team are deluged with these blood samples.

EWER: There's absolutely loads still to do.

I have a freezer full of thousands of samples from the Phase Three that we haven't had a chance to start looking at yet.

Having had very recently the experience of taking vaccines through Phase Three for COVID, where we had an enormous team of people and AstraZeneca working on it, the contrast to the team working on malaria, where there are seven of us, it's a very different experience.

(equipment beeping) We're under pressure to start churning out some data.

So it's full speed ahead.

LISA STOCKDALE: Is plate one up on mine or is it on yours?

SAM MORYS: No, but the folder's up.

NARRATOR: The team needs to analyze the children's antibody responses to R21 and the control vaccine.

Immunologist Lisa Stockdale is running a test called an ELISA.

LISA STOCKDALE: We've got quite a big variation, some of the samples have quite a lot of antibody whereas some of them don't.

We're blinded to which group people are in, but in general, it looks like the plate is developing well.

I've been doing hundreds of these ELISA plates.

Hundreds and hundreds.

(chuckles) NARRATOR: To be effective, R21 must prime the blood with antibodies that target the malaria CSP protein.

But the team also needs to know if those antibodies can actually neutralize real malaria parasites.

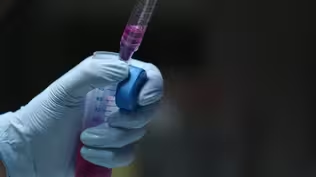

EWER: We take the parasites out by dissecting the mosquito.

So I'm just gonna hold it with one hand.

Pull the head away gently.

Okay.

So we have the head off.

You end up with two pairs of salivary glands.

They look like little fat sausages.

It's those little sacs that have got the parasites in.

Aha!

Got them.

NARRATOR: The parasites are added to lab-grown liver cells, along with blood from vaccinated children.

If the liver cells do not become infected, it suggests the antibodies should protect the children, too.

EWER: It's just a lot of pressure to get through all these samples, get the antibody data together.

Should we do both of them together then?

Could do.

HILL: I am getting emails at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning.

So a lot of people are working super hard.

I'm a little bit anxious that maybe we've had to push them too hard or we're too ambitious in our timeline.

I'm exhausted.

I'm tired, I'm stressed, I'm not sleeping, uh, yeah, I'm probably not a great person to be around at the moment, if I'm honest.

NARRATOR: All this lab effort is crucial to understanding how R21 works.

But above all, they need to know if the vaccine protects enough children in the real world.

After around a year of closely monitoring the health of all 4,800 Phase Three children, the wait is nearly over.

HILL: The key Phase Three trial is coming to the end point.

The statisticians have the data and they are analyzing it as we speak.

EWER: You know, this is something that we've all worked on for years, so to be this close, it's, it's kind of nauseatingly, sickeningly anxiety-inducing, really.

You know, we just don't know what we're going to see.

And I think we'll be all really relieved to get that result.

NARRATOR: Eleven years after R21 was first made here in the lab, after seven years of trials, over 20,000 vaccinations and hundreds of thousands of samples analyzed, an answer.

HILL: Even ups significance on severe malaria.

EWER: 72 percent, bloody hell!

Wide confidence intervals, but bloody hell, that's what... (indistinct) I mean that's... yeah, absolutely.

Great.

(sighs) Oh, God.

Get me a drink!

(sighs) Yeah.

So we have the result of the Phase Three.

So, big moment, um... As, as expected from the Phase Two, some really interesting results in there.

But yeah, really good and really reassuring and, yeah, just very happy.

(joyous exhale) (crying) (sniffles) (sighs) Yeah.

We're very happy.

Although it really didn't look like it, but... Yeah, it's just a moment I've been waiting for for so long.

But, yeah, what we wanted and what we hoped for.

So really good.

Yeah.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Barely a month later, there's a global medical conference in Seattle.

The promise of the initial Phase Three trial result is now sinking in.

Across the different ages and locations of children in the trial, around a year after they were first vaccinated, R21 has reduced cases of clinical malaria by about 70 to 80 percent.

Hey, good morning!

Ah!

NARRATOR: So the teams from Oxford, Tanzania, Kenya, Mali, and Burkina Faso gather to prepare to present their data publicly for the first time.

HILL: These people are just extraordinary.

They are leaders in their field.

Hello!

How are you?

Good to see you.

HILL: The results that have come in show safety looks absolutely fine in literally thousands of children.

And even more excitingly, the efficacy, the reaction was they cheered.

DICKO: Very, very good news.

OLOTU: You know, seeing the numbers that was a moment of excitement.

Everybody was taken aback and say, you know what?

Wow, this is, this is real.

This is, this is something.

When this result came out, I was like, ah.

Oof.

Ah!

This is, this is what I was waiting for long.

HILL: So here we are on Sunday, on Wednesday we're going to try and tell the world about what we've found.

♪ ♪ DATOO: We know our vaccine works, we know we have good data.

I'm excited to see the response.

I hope everyone is as excited as we are.

♪ ♪ (applause) I am very pleased today to be able to share with you the first data on the safety and efficacy of R21/Matrix-M, the new malaria vaccine.

(applause) MATTHEW COLDIRON: It was extremely exciting.

This is a vaccine that works, that's going to be widely available, at a reasonable price, and that could really, really make a big difference.

It's trite to say gamechanger but I really think it is.

ANNA LAST: It's very encouraging news that they have the Serum Institute in Pune who is going to be able to really scale up the production of a vaccine.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: For the team, sharing their results is a moment to savor.

R21 can't be directly compared with RTS,S-- their trials were different-- but there's now no doubt about this new vaccine's potential.

The next step is evaluation by the World Health Organization.

Its approval will be essential.

Without it, donor funds can't be used for the vaccine's roll-out across Africa.

It's a process that can take years.

(news theme playing) NARRATOR: But six months later, as W.H.O.

deliberations continue, there's breaking news.

A day of pure elation for Ghana, for science and for all of humanity, as the FDA has granted approval to a new vaccine.

REPORTER: Ghana's government has become the first in the world to clear the roll-out of malaria vaccine R21.

NARRATOR: Ghana's drug regulator has reviewed the data on R21 and approved it for use, signaling a clear and urgent demand for this new vaccine.

Days later, Nigeria follows suit and Angola looks to place an order.

But there's still no certainty that the W.H.O.

will approve the vaccine and so unlock the necessary funds.

Let's get into the manufacturing, um, details of how to scale up as soon as possible, because now I think there's a lot of excitement.

NARRATOR: In Pune, Serum's CEO has a very big decision to make.

POONAWALLA: How many doses should we then make at risk?

I was thinking around 20 to 25 million doses.

Do you think that would be okay?

SHALIGRAM: That is, so five million Angola wants, and Nigeria also wants around five, ten million, and Ghana around five, ten million, so 25 million is good enough.

Or should we make around 30 million to be safe?

I think so, we should try... Fine, go ahead, do it.

Let me know what the costing and the risk we're taking in that is, but let's just go ahead.

What's the expiry on that?

The expiry is about 18 months.

Yeah, that's a matter of concern.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Adar Poonawalla has just risked over $100 million to start production of 30 million doses of R21.

They'll be offered at the very low price of under four dollars a dose.

The gamble is whether W.H.O.

approval and sales will come before the vaccine stockpile expires.

♪ ♪ POONAWALLA: We've taken all the risk, you know, for the trials, for manufacturing, 30 million doses, we just hope that it's all worth it.

I wouldn't have the freedom to make these sort of risky decisions and bets had I been accountable to multiple stakeholders, shareholders, banks, etcetera.

Here, it's just a few people coming together and quickly deciding to go ahead on something.

Everything is now on W.H.O.

to approve the vaccine, that's all we're waiting for, and then we can roll it out.

NARRATOR: In Serum's cold storage, the shelves rapidly begin to fill with R21.

R21.

R21 storage, yeah.

SHALIGRAM: This is a place where your heart fills with a joy.

Because finally the product which will get into the humans is ready.

This entire cold room can accommodate 40 million doses, which means 10 million children vaccination.

Amazing feeling.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: It's five months since Serum's R21 production line started.

The team has been sharing continually updated evidence with the W.H.O.

that the vaccine is safe and cost-effective.

And although R21's efficacy does decrease a little over time, a booster dose bumps it back up.

And now... HILL: Hello!

NARRATOR: They've been told to expect an announcement.

TEDROS ADHANOM GHEBREYESUS: Good morning, good afternoon and good evening.

Today is a great day for health.

A great day for vaccines.

Almost exactly two years ago, W.H.O.

recommended the broad use of the world's first malaria vaccine called RTS,S.

Today, it gives me great pleasure to announce that the W.H.O.

is recommending a second vaccine called R21/Matrix-M to prevent malaria in children at risk of the disease.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The W.H.O.

has approved R21, for use in any African child at risk of malaria, a decision that should trigger the release of critical donor funds.

Congratulations!

What a great day.

OLOTU (on computer): Congratulations to you, too.

DICKO (on computer): This is really an historic day for Africa, I think.

HILL: We are not talking about hundreds or thousands, but over time, well over a million lives saved.

It, it's just staggering and, and hugely, hugely gratifying.

And you just feel, wow.

EWER: Really happy, really relieved, and, you know, proud that we've got here.

You know this opens the door for the next stage for the vaccine, which is to get out there into the real world, and, and that's the bit that I'm sort of most excited about, really.

♪ ♪ OLOTU: I'm dreaming for that day to come and I hope it will come sooner than later.

And, uh, yeah.

It's, uh, yeah, this is what, this is what I want to see.

This is what every parent wants to see.

NARRATOR: In the long term, malaria vaccines offer great hope.

With climate change opening new frontiers for malaria-carrying mosquitoes, more and better vaccines will be important in Africa and elsewhere.

And perhaps one day malaria may even follow smallpox into the history books.

But in Tanzania right now, for people like Zuhura Abasi and her daughter, R21's mass roll out in 2024 can't come soon enough.

ZUHURA (translated): I'll be very happy once malaria is no more.

That way my child will be able to study properly.

Unlike today when kids miss school for days because of malaria.

(singing in Swahili) ZUHURA: FARHIYA AND ZUHURA: ZUHURA: FARHIYA AND ZUHURA: ZUHURA: Eh?

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S50 Ep17 | 2m 34s | Today, Malaria is considered a tropical disease, but it wasn’t always that way. (2m 34s)

Inside the Fight To Develop a Malaria Vaccine

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S50 Ep17 | 4m 18s | These scientists were on the verge of a breakthrough with a promising vaccine nearing approval. (4m 18s)

Why Mosquitos Are Humanity’s Deadliest Creature

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S50 Ep17 | 3m 37s | About 80% of deaths caused by Malaria annually are young children, below the age of five. (3m 37s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Viking Cruises. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting , and PBS viewers.