Vermont Public Specials

Solar Eclipse 2024: Path to Totality

Season 2024 Episode 3 | 25m 57sVideo has Closed Captions

Experts uncover the science, history, and excitement surrounding the April 8th eclipse.

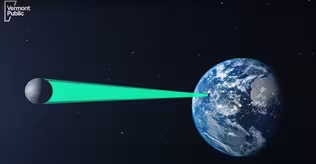

On April 8th, 2024 a Total Solar Eclipse will pass over some of the US. Host Jane Lindholm talks with experts to uncover the science, history, and excitement surrounding this rare astronomical event. Northern Vermont will be in the final path of totality, meaning the moon will appear to completely cover the sun, and Vermont Public produced this special in celebration of the rare event.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Vermont Public Specials is a local public television program presented by Vermont Public

Vermont Public Specials

Solar Eclipse 2024: Path to Totality

Season 2024 Episode 3 | 25m 57sVideo has Closed Captions

On April 8th, 2024 a Total Solar Eclipse will pass over some of the US. Host Jane Lindholm talks with experts to uncover the science, history, and excitement surrounding this rare astronomical event. Northern Vermont will be in the final path of totality, meaning the moon will appear to completely cover the sun, and Vermont Public produced this special in celebration of the rare event.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Vermont Public Specials

Vermont Public Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAround the country, people are deep in preparations for a solar eclipse on April 8th.

Here in Vermont, where we're based, we're right in the path of totality.

I'm Jane Lindholm with Vermont Public.

Join us as we explore what's being called the Great American Eclipse.

Let's learn a little bit more about what's happening astronomically during an eclipse.

We're at the Fairbanks Museum and Planetarium in Saint Johnsbury.

And waiting inside for us is Planetarium director Mark Breen.

Hi, Mark.

Hi, Jane.

Nice to see you again.

Good to be here.

So I think most people have a little bit of an understanding about what a solar eclipse is, that the moon is passing between the Earth and the sun, blocking out the light of the sun.

But can you go into a little more scientific detail for us about what a total eclipse is?

Sure.

It's one of those mysterious things, because very few of us ever see one.

They're very rare, as far as that goes.

And so what happens is the Earth's moon, orbiting the Earth, takes only a month to go around once.

And so you would think, well, maybe we should have an eclipse every month.

But we don't, because the moon has to be perfectly lined up.

And as it turns out, the moon's orbit is just slightly tilted.

So it doesn't line up almost all the time.

And that's why it's such a rare event.

But when it happens just perfectly, a very thin strip on the Earth sees the shadow.

It takes anywhere from maybe a minute, some places may see it as long as 4 or 5 minutes.

But it's a relatively brief little moment where suddenly the sun disappears.

And sometimes when there's a solar eclipse, the moon is a little bit farther away from the Earth or a little bit closer to the Earth.

Does that affect what we might see in an eclipse?

Yes.

In fact, sometimes if the moon is at its most distant point, it actually doesn't completely cover up the sun.

You get this ring of light around it.

It's called an annular eclipse or the ring of fire, they sometimes say.

And then at other times, if the moon is much closer, then we can have an eclipse that will last as long as 6 or 7 minutes.

So you said this is a pretty rare event, but it could happen anywhere on Earth.

So how often do we see total eclipses?

So they worked out an average that in any one location it's about every 400 years.

Oh, my gosh.

Every 400 years.

Yes.

But there's a place in Tennessee where the eclipse in 2017 will basically happen again this year.

So they get two eclipses in seven years.

So what is the path of this eclipse?

It's being called the Great American Eclipse because it's passing through so much of North America.

Right.

But it actually starts out in the Pacific.

It takes a few thousand miles before it gets to Mexico.

It cuts across northern Mexico and then through Texas.

It goes through big cities like Indianapolis, then into Cleveland, Buffalo and then right across northern Vermont.

So given that the path is wide in terms of the swath it's going to cut across North America, it's still pretty narrow in terms of the path it's going to cut of totality.

Even if people are seeing part of the eclipse, many, many people will not be able to see the total eclipse.

How wide is that path?

Right.

I think this particular one averages about 109 miles.

But you're right, the entire United States will see at least a partial eclipse.

But it's a relatively narrow path, even though it's over 9000 miles long.

Wow.

What determines how long you get to see totality?

Right.

So the center part of the eclipse would see the longest amount of the eclipse.

And in this particular eclipse, that's going to run about 3 minutes and 30 seconds.

As you get toward the edge of that shadow, it decreases.

And in fact, within just a few miles, it goes from one minute of totality to zero.

Have you ever seen a total eclipse?

I have not.

I've seen partial eclipses.

I've seen an annular eclipse.

But I've never seen a total solar eclipse.

So what does this feel like for you as someone who has studied this kind of thing for so long?

I have to say, in some ways, I'm very anxious.

I can't wait till it gets here.

But it's absolutely fascinating.

And as much as I've studied, you know, astronomy and eclipses and so forth, this has just allowed me to dig into it a little bit deeper.

Well, Mark, thank you very much.

I really appreciate your time and expertise.

You're welcome, Jane.

Like Mark, I've never seen a total solar eclipse.

The last time one occurred in Vermont was in 1932.

And the next one won't be until 2079.

After that, you have to wait abo 300 years to see one in this region.

So here's hoping it's not cloudy in April.

Eclipses are happening somewhere in the world about every 18 months or so.

And eclipse chasers and scientists travel all over the globe to see them.

That includes solar physicist Martina Arndt, a professor at Bridgewater State University in Massachusetts.

Professor Arndt, thank you so much for talking with us.

It's a pleasure to have you here.

It's a pleasure to be here, thank you.

How many total solar eclipses have you seen?

I've traveled to 12 different eclipse sites, but sometimes we have snow, sometimes we have clouds, sometimes we have rain.

So I would say we've probably se about 5 or 6 out of those.

When you say you've been to 12 sites, but you've only seen 6 or 7, what happens when it's cloudy?

Because I have to say, here in Vermont, where we're based, April is a pretty cloudy month, so we may be experiencing that.

So what happens is we don't get any data and we're sad, but we realize it's part of how this works.

And the skies do get darker and you do see the overall light in the area go down, but you don't get to see the sun itself.

Okay, so we'll experience darkness.

We just won't get to see that amazing sight of the eclipse.

Yeah.

So, you're sort of an eclipse Chaser.

Yes.

What data are you trying to get during an eclipse?

Well, I think this would be a good time to say that I'm a part of a very large team, and that entire group is led by my mentor, Dr. Shadia Habbal at the University of Hawaii.

But what she's really looking for in the end is to understand some of the puzzles that we still have about the sun.

Like, why is the upper atmosphere of the sun so hot?

It's hotter than the surface of the sun.

And we call that the coronal heating problem.

There's also charged particles leaving the sun at two distinct categories of speeds, and we don't know why those are different and where they're coming from.

And another area of research that she's been doing is there are things called prominences, which are large magnetic structures that are filled with plasma that come out of the sun and they're explosive and they're big.

And we don't quite know the origin of those.

And so that's the reason why we need eclipses to be able to get these data, because otherwise the sun is too bright and we can't get the information we need unless the main body of the sun is actually closed off and blocked to us.

But it sounds like having seen 12 now, and there are others of you out doing this all the time too, tha it's not something where one eclipse is going to give you the answers.

Absolutely not.

And the problems that were that scientists are looking at are really, really big ones.

And it takes a village, Literally, to try and chip away at this problem with models.

And then once you have a model, you need data to see if it fits the model.

And then you iterate and you move and you move.

And it takes time.

It does take time and it takes a lot of people.

How close are you to learning something new that humans didn't know before?

I would say that from almost every eclipse where we've been able to get data from, you know, Dr. Habbal and all of her colleagues, and occasionally I get to be part of these research projects as well, we do learn a little bit of something every time.

Where are you going to be for this one?

I will be in Kerrville, Texas.

A very large team.

We will be spread along the path of totality in multiple spots.

But in Kerrville, Texas, we hope to have really good weather.

And the reason why we have multiple sites is that if one site has, you know, bad weather, then maybe another one will have good weather.

And then, like in the eclipse of 2017, we had five sites and they all had clear weather.

And so we actually got more data because it was over a longer period of time and there weren't a lot of changes, really, betwee you know, the first set of data and the last set of data.

But together, it made a very nice large dataset.

Well, Professor Arndt, thank you very much for sharing your expertise with us, sharing your knowledge and good luck.

I hope you get sunny weather for your eclipse.

Me too.

Thank you.

And I hope you do, too.

Thank you so much.

Watching a total solar eclipse can be a once-in-a but if you're not careful, it can also be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to do serious damage to your eyes.

Looking at the sun is never safe, even during an eclipse.

And one of the problems is you might not know you're doing damage until it's too late.

With a lack of pain receptors in our eyes, it's hard to tell whether you're actually doing permanent damage or just making yourself uncomfortable.

So how do you see the eclipse safely?

Well, one thing we want to say right at the start is this is not a good option.

A pair of sunglasses will not block out enough of the sunlight to be safe.

So just ditch the sunglasses altogether.

One good way to watch the eclipse is to get a pair of eclipse glasses.

These glasses allow you to safely look at the sun while the eclipse is occurring without damaging your eyes.

If, like me, you wear glasses and those aren't very comfortable, you have options too.

Something like this, an eclipse viewer that can go over a pair of prescription glasses, may be a good option for you to be able to safely view the eclipse.

Now, guys, what about welding helmets?

A lot of people have that question.

And in fact, a welding helmet can be a safe option for viewing the eclipse if you have shade 12 or higher.

Now, if you don't know what shade your welding helmet is or what I'm even talking about, you're not a good candidate to wear a welding helmet during the eclipse.

Perhaps you're a budding photographer or astronomer and you want to take photographs or see the eclipse through a pair of binoculars or a telescope.

You still should not be looking through those lenses without a filter, so you're going to need to get a separate solar lens for your camera or your binoculars or your telescope and even, in fact, for something like your cell phone.

You could damage your cell phone by taking pictures of the eclipse without a lens like this.

So something like this can fit easily over your cell phone so you can take pictures.

That being said, cell phone pictures rarely come out very good.

So if you're taking pictures with a cell phone, you might just want to put it back in your pocket and enjoy the experience of a lifetime.

If you're wondering how to view the eclipse safely and maybe you don't have any eclipse glasses, you can make a pinhole viewer with materials you may already have at home.

We're at JFK Elementary School in Winooski, Vermont, today to learn how.

Hi, everybody.

Do you know what we're going to do today?

Were going to make glasses for when a solar eclipse happens That's right.

We're going to make eclipse viewers.

They're called pinhole viewers.

So you have a box with two holes.

One of these holes is going to be an eye hole and one of these holes is going to be covered.

But before we cover the hole, we're going to put our white piece of paper inside our box on the side that does not have the holes.

This is like a screen.

This is like a movie screen.

And then you want to slide it down and then stick it to the bottom.

Perfect.

All right.

We ready for the next step?

This is the tin foil step.

But remember, you want to keep your tin foil as straight as possible.

And you're going to pick one of the two holes.

It could be either one, up to you, whichever one feels more comfortable to you.

And you are going to put the tin foil over the top of it, so it's as straight as possible, and then you're going to tape it down.

Everybody's boxes look great.

Okay, so now we need your adults to help with one more step.

So your teachers are going to come around and help you seal your box.

So you know how it's closed on one side?

Now we want to close it on the other side, too, so it's a nice closed box.

You want to make sure they're taped as tightly as possible so that no light gets through.

Okay.

Final step in our eclipse viewers.

This is your eye hole.

This is your viewer.

So you're going to look through here.

But how are we going to get the sunlight in?

We're going to get the sunlight in by having one of your adults come around and poke a hole in the tin foil.

Remember I said these are called pinhole viewers?

So you just want one little pinhole.

Are you ready?

Yes.

What's your question?

Are you supposed to look into both of the holes?

Just the open square.

Okay.

So we're going to take our viewer, we're going to look through here and I'm going to position myself until I can find that light.

And now I'm seeing there's a circle of light projected right on the back of my pinhole viewer.

And that's what it's going to look like during the eclipse.

You're not going to face the sun.

You're going to face away from the sun so you're definitely not damaging your eyes.

And you put your eye up to the pinhole viewer and you can see the sun and you'll be able to see the eclipse happening.

I saw it too.

I see it.

Yeah, cool.

Thats better.

I see it.

You see like a circle?

That's going to be what the sun looks like.

So now we know how to safely make an eclipse viewer.

Meanwhile, a lot of communities around the path of totality have been planning big events where people will be able to get their own glasses or watch through telescopes.

Vermont Public reporter Lexi Krupp has been finding out more about what's been underway.

Thousands of people are expected to visit Vermont to see the eclipse, and many of them will need a place to stay.

Hotels in the region said they started receiving calls to book rooms about two years ago.

As of early February, about 80% of short term rentals in the region are already booked.

That's up from about 10% from the same time last year.

Lots of Vermonters are getting creative to sell accommodations, including a church in Burlington.

We knew that already people were struggling to find affordable places to stay in Burlington.

And from the very get go, we knew that this eclipse was happening and that it would be a really fun event and a way to build community and connection.

And because we are a religion that really finds lots of meaning in events that are happening in nature, we knew that this would be something that we wanted to organize around, and so we created a homestay program where we've asked congregants to host, basically, strangers who are coming here for the eclipse as a fundraiser for the congregation, but also as an act of hospitality.

I run a short-term rental in my building and I recognized right away that I could rent this out for a good amount.

But then when we started talking about this project, I just said, Im just going to donate it to the UU Society.

So that became one of the one of the offerings, and it went immediately.

We're really pleased with how many people have snapped up.

We still have some left.

I don't know if what will be the case by the time this airs.

We had somebody send an email today from California.

So we know that people are getting the word and that they're buying them up.

This is a radically welcoming, radically loving community.

And so this feels like a very friendly, welcoming thing to do to the universe.

You know, come appreciate the wonderfulness of Burlington in our homes, and we can all experience the eclipse together like people have done for thousands of years.

Lots of places have been considering how to take advantage of the eclipse, including a school in Morrisville, Vermont.

There, one science teacher has been planning for the total solar eclipse for years.

I have been a teacher at People's Academy for four years and so for the last three, we've offered the astronomy class as an elective.

It was decided to offer it because we have an observatory and more kids will just know about it and know that it's a resource they have at the school.

The observatory is actually from 1931 and so this is the telescope, and you can point it in any direction.

And then what's really cool is the dome itself rotates, so we move this and the whole dome rotates and then you turn this and the slit opens.

And so then you can look at anywhere or in the sky.

It's the only public high school I know that has an observatory.

And it's cool to be able to show students in my class.

Since figuring out that this school is in the path of totality, I reached out to my principal and we ordered solar eclipse glasses for every student at the school so that they can take them and observe the solar eclipse from wherever they're going to be on that day.

And then in terms of the actual day, I have told my students, if they want to stay here, I'm going to have two solar telescopes and we're going to be observing from, you know, when the moon just starts to move in front of the sun, all the way up until totality, which is quite some time.

But mostly I've just encouraged them, Like, just be somewhere where you can see it.

Like, you don't have to be at school, but take the glasses and use them, because, you know, for some people this may be the only opportunity they have to see a total solar eclipse.

The last total eclipse in Vermont was in 1932.

At the time, the State Motor Department issued special rules for drivers.

A museum in Boston asked residents to document how animals behaved.

And a European astronomer flew thousands of feet above Maine to take photos and study the sun.

This year, the state estimates that over 100,000 visitors could come to Vermont to view the eclipse.

It's not just the modern day where humans are fascinated by solar eclipses.

Throughout human history, we have tried to interpret and predict solar eclipses.

We spoke with Thomas Hockey, a professor of astronomy at University of Northern Iowa and the author of “America's First Eclipse Chasers, ” to learn a little bit more about the timeline of how humans have thought about solar eclipses.

What can you tell us about the earliest references to solar eclipses?

What are they?

What do we know about when people first started being able to record-- and wanting to record-- that a solar eclipse had occurred?

Historians will tell you that one of the hallmarks of civilization is writing.

And so it's interesting to look at the earliest writing on clay tablets made in Mesopotamia more than three millennia ago.

Similarly, on bone in China.

And what did they write about?

Many things, to be sure, but one of the things they wrote about were eclipses.

And what did they say?

These were records of what happened.

Did the moon seem to disappear?

Did the sun seem to disappear?

The hope being that if enough of these or records were made, that eventually it might be possible to find some sort of pattern in them so that one could actually predict these events, which were taken as omens, and therefore prepare to do something about them before they actually arrived.

And in fact, that did take many centuries to find such patterns.

But find them they did.

Be it in Mesopotamia or China, or also in India, in the new world, the Mayans.

Pretty much any civilization that you can name did this.

Total solar eclipses, because they were a surprise, were almost always considered negatively in the past because they were an interruption in the normal, fairly regular behavior of the luminaries in the sky.

They were an omen of something bad that was going to occur.

The disappearance of the sun was a big deal.

It must be a big omen.

Probably not just for anybody, but for the government, for the paramount or the king himself.

And so what did they do?

If you, over many centuries, kept track of them, you might have a chance of at least, if not predicting, at least saying when an eclipse might occur, and then take what you consider to be necessary steps, which involved certain rites and loud noises to scare whatever was taking the eclipse away.

Or, in the case of the Babylonians, pull a switch, grab someone off the street, set them on the throne, put the crown on his head while the real king went hiding, and this false king would take whatever fate that the eclipse had in mind for the king.

So, Professor Hockey, move us through a timeline, very quickly as if we're on an express train through time, about how things changed as people started to gain more knowledge or at least more experience and more of a historical record about these eclipses happening in the past.

Well, Isaac Newton happened.

His theory of gravity made it possible to predict eclipses quite well.

So we had reached a point where we could say there would definitely be an eclipse.

In the 19th century, astronomers noticed that you could see some interesting things, the outer layers of the sun, and study those which were normally invisible because of the bright layer of the sun's normally yellow disk.

And so they started mounting expeditions specifically to observe eclipses.

They brought other tools to bear, like photography, so people wouldn't have to just take their word for it.

And the stories of these expeditions to these particular places on Earth where the eclipses were visible are enjoyable adventure reading even today.

Well, it's amazing: We've gone from bad omens to a sign of wonder and awe for many people around the world when they're able to see a solar eclipse today.

And in particularly 2024, Where, if one wanted to choose a path, this one would be the one, which goes over so many American cities.

More people will see this eclipse than perhaps ever before.

So if you're planning to view the Great American Eclipse on April 8th, you'll be in good company.

Now, if you are planning to travel to see the eclipse, you're going to want to make sure to give yourself plenty of time.

Officials warn there could be a significant increase in traffic along the path of totality.

So you're going to want to get there early and think about perhaps staying late.

Once you're in place to view the eclipse, be sure you have your safety precautions.

Eclipse glasses are a great way to view any partial eclipse.

During the time of totality, you can take your glasses off for just those brief moments.

And if you're planning to take pictures, make sure you have a filter, a solar filter, for your lens.

And of course, dont forget to enjoy the experience.

Even with all our modern technology and scientific awareness, a solar eclipse is still an amazing experience.

So enjoy that awe-inspiring view the same way humans have done for millennia.

For Vermont Public, I'm Jane Lindholm.

How to make a pinhole viewer for the solar eclipse

Clip: S2024 Ep3 | 3m 5s | One of the safest ways to view a total solar eclipse is by using a pinhole viewer. (3m 5s)

How to safely view a solar eclipse

Clip: S2024 Ep3 | 2m 17s | Demo of various ways to safely watch an eclipse. (2m 17s)

The science behind solar eclipses

Clip: S2024 Ep3 | 4m 25s | Astronomer Mark Breen answers common questions about solar eclipses. (4m 25s)

PREVIEW: Solar Eclipse 2024: Path to Totality

Preview: S2024 Ep3 | 2m 18s | Vermont Solar Eclipse 2024: Path to Totality," premieres Wednesday, March 27th. (2m 18s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Vermont Public Specials is a local public television program presented by Vermont Public