On the Cover

Episode 4 | 54m 39sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Music magazines played a pivotal role in elevating music photography to iconic status.

Music magazines played a pivotal role in elevating music photography to iconic status, providing a visual context for some of the world's greatest bands and their music. Journalists, musicians and publicists among others join the music photographers who shot some of the most memorable front covers to discuss the uncensored and often never-heard-before stories behind these amazing photographs.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionAD

On the Cover

Episode 4 | 54m 39sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Music magazines played a pivotal role in elevating music photography to iconic status, providing a visual context for some of the world's greatest bands and their music. Journalists, musicians and publicists among others join the music photographers who shot some of the most memorable front covers to discuss the uncensored and often never-heard-before stories behind these amazing photographs.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADHow to Watch Icon: Music Through the Lens

Icon: Music Through the Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[theme song playing] Sometimes you see a great cover and it just catches your eye.

But that's the whole idea of it.

Magazines for me was all I need, right, back in the day.

So I would be picking up "Blues and Soul" or "Touch Magazine."

JOHN VARVATOS: I would go to the record store, and sit down on the floor of that store, and flip through those pages, looking for number one.

What's the next record album that I'm going to buy?

Who's cool out there today?

What's interesting about it?

CHALKIE DAVIES: To me, if the kid cut a picture out of the "NME, and put it on their bedroom wall, I've done my job right.

ART ALEXAKIS: Magazines were everything.

You needed to be on the cover of the magazine.

You needed cool, iconic images.

If you were on the cover of "NME," "Melody Maker," "Q," "Mojo".

Do they sell records?

Yeah, they sell.

And great for your ego.

Ooh, I look quite good on that.

DANIEL O'DONOGHUE: Our first magazine cover was Hot Press in Dublin.

That was our arrival.

It's the bible.

It's NME, it's Mojo, it's Q, all of those wrapped into one.

I used to buy that magazine, and now I'm on the front cover.

ALICE COOPER: Cover of Rolling Stone meant you were something, you know.

Because they just wouldn't waste that cover on anybody.

They were going to put somebody that was going to sell copies.

You obviously want a cover, but it's usually more big of a deal for the record label.

By the time it got to, like, that "NME" cover and bonkers and all that, I was that happy.

Yeah, I felt that was an achievement.

And when you see that cover, like immediately, if you see something that's either iconic, or sucks you in, you might not have time at that moment to read the entire article.

But you definitely want to look at those images.

[theme song playing] MARK WAGSTAFF: Music photography exploded in the '60s.

And it went from strength to strength all the way through the '70s, and even into the '80s when there was still money around.

GERED MANKOWITZ: It became very professional and very sophisticated.

And the editorial photographers were representing an increasingly evolving and sophisticated music press.

In the UK, you have "Melody Maker," "Record Mirror," "New Musical Express," "Disc," and "Music Echo."

And in America, you had "Rolling Stone," "Creem Magazine," and lots of others.

And so this whole industry evolved and developed.

And that gave photographers a fantastic in.

ALEX LAKE: It never gets boring to shoot a magazine cover, because, I guess, editorially, that's something, you know, I always dreamed of doing.

You're flying around the world.

You're taking pictures of extremely photogenic people in extremely photogenic places.

It's just brilliant.

CHRIS CHARLESWORTH: The seven years that I spent working for Melody Maker were amongst the happiest of my life.

If you love your rock and roll, who wouldn't?

You'd give your right arm to fly across America in Led Zeppelin's private plane, talking to Jimmy Page, or to go flying around with Keith Moon, watching him lob a TV set out the window.

I mean, [exhales].

I love what I do.

I love working with musicians.

I love working with magazines.

NEAL PRESTON: So many people have told me, I've seen your photos in magazines for years.

I love the fact that I became the one degree of separation between the fan and the artist.

If you were on one of the major magazine covers, you were being endorsed by that magazine.

And that magazine was basically saying, to us, you are the most important band in the world at this particular moment.

What you do tend to think a lot of the time is the reaction that you want from the audience.

And the reaction you do want from the audience is, who the [bleep] are these guys?

I need to know.

You have an opportunity, you have to try and take it, really.

Because you never know.

You might never get to be in a magazine again, so it's best to do it naked.

You want the character of the person to come through.

Even if you're doing a conceptual photograph or a funny photograph, you still have to get the essence of the person in the picture for it to be successful.

[music playing] BARON WOLMAN: One of the most exciting things about "Rolling Stone" when it began was that anything was possible.

We had no limitation.

We had no marching orders.

We could do anything.

I'd adored that magazine, and that's how I got to know Baron Wolman, because he was one of their photographers.

I just absorbed everything he shot.

BARON WOLMAN: Nobody was covering the musicians, the fans, the music, and we were right in the midst of massive social change that was really visible in the Bay Area, San Francisco.

You can see it in the way people dressed, what they were talking about, their belief in changing the system.

We knew we were doing something good.

It was a very simple layout and very simple cropping.

I mean, laying out of the pictures, but always really, really good.

ALICE COOPER: I mean, there had to be some sort of a table of people sitting around going, who do we think is going to be the next big thing.

I think it's Alice Cooper.

Boom.

And there he is, there's Alice Cooper.

And there's makeup smeared, that's got attitude.

Or it's Bowie, and it's all glammed out.

They didn't waste a cover.

They made sure that whoever that person was going to be, was going to be somebody.

Many of these stories start out the same way.

I'm in my kitchen in Laurel Canyon, and the phone rings.

That's the way every picture starts, you know.

In this case, it was the editor of "Rolling Stone" in New York saying, Henry, do you have a little time this afternoon?

[funk music playing] We've heard the Jackson 5 are down at Motown Records, down in Hollywood, would you go down there and take some photos of the boys, and especially Michael?

I think they might have said for the cover.

But they wanted a nice portrait of Michael.

And I'd met him before, shooting for the teenybopper magazines.

I knew those guys, you know.

The big brothers were real friendly, and Michael was kind of quiet, you know.

Very quiet, very polite, very friendly.

So I went down and laughed and joked with the big brothers.

And you know, Michael was kind of sitting on the couch, and I took a ton of pictures for like an hour.

And then I was sitting, talking to Michael, and he was playing with the cigarette lighter.

And I was just sitting there taking pictures of him, and-- I don't know.

We just talked a little bit, and I just kept, just kept shooting.

Kind of candids, you know, he wasn't like posing, really.

And one of those became a cover of "Rolling Stone."

This was '70, '71.

And he just sang like an angel.

And I mean, I remember photographing in tears.

The sound of his voice brought tears to my eyes.

It was so pure and so beautiful.

I mean, yeah, he turned into who he turned into.

But, you know, life is chapters, you know.

That was one chapter of his.

We all go through chapters.

JULIAN LENNON: Being on the cover of "Rolling Stone was a bit of a weird one, you know.

I mean, I was on it.

['I Don't Wanna Know' by Julian Lennon] ♪ I don't wanna know what's going on ♪ ♪ But I don't wanna know what's right or wrong ♪ Whether it was based on my own merits or of my family ties, you know, I think both of those elements may have played into it.

I would hope so, I would like to think that.

It was very early days.

I mean, I looked like I was 16.

For many artists, at least back in the day, with Rolling Stone, you had a sense that you'd arrived.

You'd been accepted within the community.

You'd been admired for the work that you've done, that, you know, finally made it.

Little did I know.

[laughs] ♪ I don't know what to do ♪ Being on the cover of "Rolling Stone, it's an iconic position.

That, again, is part of the history books.

That's something that as long as we live, will be there, being in the journals forever.

And I think that's a very, very special place to be.

♪ Oh, baby ♪ Here in the UK, you have to remember, there were five weekly music papers.

There was a Melody Maker-- which was what I worked for-- NME, Sounds, Record Mirror, and Disc.

So you add all that together and there's a huge amount of promotional potential.

No other country had anything like it.

We were very powerful.

New magazines come along, like the NME, and bring a whole new dynamic to music photography, basically, creating a demand for pictures and wanting to use them in a different way on covers, inside the pages, and want interesting, exciting photographs.

So photographers come along to service that.

[brief musical montage] It was Easter Monday in 1994.

I was skint and it was like 250 quid to go and shoot for this magazine called Loaded.

I was given the name of this guy that I had to ask for when I got to the hotel, which was Noel Gallagher.

As far as I was concerned, he was maybe the manager of the band.

I go into this room that is not much wider than the bed that's in it.

I mean, if you open the door properly, you'd probably bang the door on the opposite wall.

This Noel Gallagher guy is on the bed, and he barely bothered to kind of acknowledge my presence in the room.

He had this address book, and he seemed like he was finding every number in the address book.

And it was the same thing every single time, he'd go, all right.

See you later, kid.

Uh-huh.

See you later.

Hang up.

And he did it about 20 times.

And I'm just thinking, who's our kid?

You know, I'm from Guildford in Surrey.

I'd never really met people from the North before.

They were like an alien species to me.

I'm like, who's our kid?

Finally, after 20 calls, we have to go meet our kids on the corner of a street, somewhere in Manchester.

And we just see this group, like bowling towards us.

They've got that lollopy walk that everyone knows now.

But I've never seen a walk like that before.

And this guy is coming towards us in like blue Adidas tracksuit bottoms, a red jacket, Adidas trainers.

And I said to Noel, who's that?

And he goes, that's our kid.

[distorted guitar chord] He introduced himself.

He said, hi, I'm Liam.

We decide that we're going to go and do the pictures at Maine Road Football Stadium.

And Liam explains to me that he's a Man City fan.

He says to me, do you support a team?

And I said, yes, I support Arsenal.

And he's like, I don't talk to you anymore.

So we have like five minutes of banter.

We get to the Maine Road.

We shoot these pictures.

And then Liam's just like, what about if there's one where I like run up-- You get on the floor with the camera, and what if I run up, and I just kind of boot ya, because you're Arsenal.

I was like, OK.

So I'm on the floor, and he does it.

We did it three or four times.

And that was the picture.

It ran at Loaded.

And the editor of Loaded, it was a guy called James Brown, he really loved that picture.

They have the swagger, and that's what elevates it.

That bit that you need to make things iconic, and the photographer was just lucky enough to be the one that was there.

PHIL ALEXANDER: The role of the magazine is to tell the flaming story.

We happen to house it in a cover the people might like.

But actually, the core engagement of magazines, is still storytelling.

And of course, that translates into words and pictures.

ALICE COOPER: I think the shot that Annie Leibowitz did of me with the snake around my face, grimacing like that, on the cover of Rolling Stone made people go, I've got to read this.

I've got to see what this guy is about.

I know if I was 16 years old, I'd have to go see what kind of band that was.

Because it was just the beginning, there was no internet.

Then when they get there, you nail them.

You make sure that they're fans forever, because you don't just advertise it.

You deliver.

One of the great things that came out of the '60s was this idea of the photographer as the storyteller.

That I have this freedom to create an image in such a way with a established artist that's not just about taking their shot, you know.

That is about having them pose in a certain way.

VIKKI TOBAK: Annie Leibowitz, certainly iconic and associated with Rolling Stone.

These beautiful portraits on a very simple background started with her.

You have Annie Leibowitz and her amazing shot of Yoko Ono, clothed, and John Lennon, naked as a baby, behaving like a baby, embracing her.

You're like, what's going on here?

RANKIN: Him, naked, up against her, and like in an embryo position, and the timing of it, and everything about that picture is incredible.

It's kind of who they are.

And there's a moment here that maybe Annie orchestrated somewhat, but that John and Yoko got involved with and responded.

And they created this very iconic image.

[cameras clicking] CHALKIE DAVIES: We were asked to do an Elton John story, and everybody was trying to get a picture of him with his hair transplants.

So the one way to defeat Fleet Street would be to do it in the NME.

It was all supposed to take place in his office.

And then I got the call, and he said he'd rather that you went out to his house.

And so there was this Rolls-Royce outside.

And it took me down to Windsor, and I'm sitting in Elton's kitchen.

And I said, then where should we do the pictures?

And he said, wherever you want.

Just go, take a look around the house.

I ended up in his bedroom, and there's this 16th century bed in there.

And on the edge of the bed was a bag, and it was an Omo bag.

And I went back down to the kitchen, he said, so where did you end up?

And I said, in your bedroom.

And he said, great.

Let's take some pictures up there.

He said, did you notice the bag?

I said, yeah.

He said, there's a reason for that, you know.

Surely, you understand.

And I said, yeah, I do.

And he said, the problem is that I live next door to Windsor Castle.

And I'm always, you know, hanging out with the queen mom, and stuff like that, but I can't get a knighthood because I'm gay.

And they won't give a knighthood to anybody who's gay.

He said, but I'm sick of living this lie.

And he said, so what I want to do with you is, can we possibly introduce this?

And at the same time, I've had a hair transplant.

But the hair transplant was not very good.

So I did most of the pictures with a hat on.

And then I did some with the transplant.

I showed them to John Reid, who managed Elton and Queen.

And John said, you can't use that.

I said, I know.

You need another 20 plugs.

So the interview was put off, I think, by four or five months.

And I went back, and I said, you know, we should do something that's just a little bit more formal.

And he went off to get dressed.

And he came back.

I'd never seen anybody with silk socks that were like stockings.

And he just sat on the bottom of the stairs.

And I said, just be Elton.

Just, just be yourself.

The cover ran and the word bisexual might have been mentioned once.

But that was enough, because then after that, he did Rolling Stone and he was a bit more explicit.

And then, you know, he was able to be the person he really was inside.

PHIL ALEXANDER: Music photography lies at the heart of what magazines do because it absolutely, it tells you, without the words, just what's important.

You look at a picture and you make a value judgment as a reader straightaway.

Are you in or are you out?

Now that isn't a question of you having to read a 3,000-word cover story.

That's just an instinct that you have.

['Suzanne' by Leonard Cohen] ♪ Suzanne takes you down to her place near the river ♪ DEBORAH FEINGOLD: So that photo of Suzanne Vega and Leonard Cohen, the origins of that, was Rolling Stone did a special on young artists selecting mentors.

So she had selected Leonard Cohen.

This was shot in my studio, and they had never met before they came in.

Even though I've taken a lot of pride in saying, I am so spontaneous, or whatever, this was one of the only shots that I actually visualized before.

When I thought of mentoring, I just thought of hands on head, and nothing deeper than that.

♪ And she shows you where to look ♪ ♪ Among the garbage and the flowers ♪ DEBORAH FEINGOLD: A few years ago, Suzanne spoke about what that photo session with Leonard Cohen was like.

And what she said was, she could hear his heart beating in her ear as it was pressed against his chest, and how nervous that had made her.

And I was touched that it had had as deep meaning for her as honestly it had for me.

So for me, that image has my name on it, that I identify completely as mine.

♪ And you know you can trust her ♪ ♪ For she's touched your perfect body with her mind ♪ DEBORAH FEINGOLD: They didn't even know each other.

They'd never met.

That was the first time, and it was a very short shoot.

And it was perfection, you know.

It was amazing.

[rock music playing] If I'm shooting a cover feature for Q magazine, I'll have a brief, and I'll work to that.

You're just trying to shoot the best images you can get.

[rock music playing] But I will consciously know when I'm shooting shots that I think are for the cover.

And I'll frame them specifically to work on the cover, because I'm conscious of where the logo is, where the headline might be, all the other type that needs to fit in.

PHIL ALEXANDER: What you really need is a team of great photographers who can deliver things when something completely unexpected happens.

And the question is, really, is their relationship with the artist good enough for them to capture that moment?

And actually, you know, the history of rock and roll is littered with those kind of moments, where, you know, the best photographers, the answer is absolutely yes.

MARK WAGSTAFF: It's so exciting when that shoot comes back to you, and you see what amazing work can still be produced even to this day.

So amazing, photographers are working now, who really do have great ideas and really push the boundaries.

RACHAEL WRIGHT: Q have quite a set look for their covers.

It's quite traditional, in a way.

And with The 1975, the way they curate their aesthetic, is so interesting.

And I also like how they doubled down on just doing what they do.

And their music is quite weird, and so I didn't want to waste the opportunity by just taking a boring photo of them.

[ethereal music playing] And I went to the house that they were recording at in the Hollywood Hills just to have a chat with Matty, and we sat by the pool chatting about what we could do.

And just offhand, Matty said that, let's do it underwater.

And I don't know what came over me, but I was like, yeah, we could do that.

Ooh!

That was the day I found out why underwater photography is its own genre and I shan't be trying again.

I went and looked into like underwater camera housing, and it cost thousands and thousands of dollars.

So I rented one, and I picked it up that morning, didn't know how to use it.

Luckily, I had an assistant.

But he also didn't know how to use it.

[laughing] And I remember turning to the manager, just as we were about to get in the pool, just saying like, this could be a disaster.

But if we get one frame out of it, I'll be happy, which isn't like me, because I want to get it right.

I'm such a perfectionist.

Luckily, they are so committed to making something look good, like I needed their input.

I needed them to collaborate.

And I think, with music photography, it does have to be a collaboration.

I think Matty actually suggested doing a shot where they were all kind of together-- which was not easy logistically, because getting to the bottom of the pool, and me being down there at the right time, and I couldn't quite see through the viewfinder because-- Yeah, it was all awful.

All the outtakes from like before and after that one shot is just like chaos of bubbles and boys pulling other boys and like clothes and like faces and just-- and then they would settle into that position for maybe at two seconds, three seconds.

And I would just have to make sure that I was settled as well, and just shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot.

There were so many-- I can't remember how many hundreds of shots we took in the pool.

But I remember seeing that one in the back of the camera, and I knew that was the one.

And I showed it to the manager, and he was like, that.

That's the cover.

And I was like, that is the cover.

Um, yeah.

It was quite stressful because the magazine wasn't sure.

So we had to Photoshop Matty's eyes open on the cover.

I spoke to the writer who did the interview with them afterwards, and I showed her the unedited version of the picture.

And she was like, that goes perfectly with my story, because it's about Matty's heroin addiction.

And the others supported him through that, and they sent him to rehab.

It wasn't a question that Matty would have to pay for his own rehab.

It was taken out of band money, because they're all in it together kind of thing.

PHIL ALEXANDER: What we're really trying to engender within the audience is just a reaction.

Fundamentally, at its core, it is like, oh wow.

That's cool.

I've never seen that.

You want that thing that just makes them stop and look.

ALBERT WATSON: There was no point in me just doing a portrait of Mick and sending that into Rolling Stone for the heroes of rock and roll.

It wasn't-- it wasn't going to cut it.

So just spontaneously, I thought of doing a portrait of Mick and then doing a portrait of the leopard, a double exposure.

But I never thought it was going to work.

A leopard is dangerous, and Mick knew as well.

He said, I'm not totally comfortable with the leopard.

And the first thing that happened was the leopard went for him, you know.

Kind of like this, you know.

This is before Photoshop, and this is when things happen in a camera, nowhere else.

I did the leopard first.

We put a small piece of meat on the lens, and the leopard just lowered its head and just stared into the lens.

It never moved.

Then I rewind the film, it was Hasselblad, and I split the exposure because I knew it was going to be double exposed with Mick's face.

And remarkably, 4 of the 12 shots were a perfect match.

[light guitar music playing] It was the agreement that I had to send the shots to Mick first before I sent it to Rolling Stone.

He looked at them, and said, oh, it looks great.

The next morning, when it came in on the answering service, there were three calls from Mick.

He said, I don't want you to give that leopard double exposure shot to Rolling Stone.

He said, because I want to use that for an album cover.

So there was a huge fight between him and Jann Wenner, and he didn't use it for the album cover.

[music playing] [rock music montage playing] CHRIS FLOYD: I had to go up and photograph Shaun Ryder of the Happy Mondays.

Yeah, of course, I want to do it.

But I'm also terrified because the legend always comes first.

I get picked up by his cousin, who's also kind of a fixer and sort of tour manager, really.

And we're going to go to Shaun's house, his cousin says to me, right, before we get to the house, I've got to go to this glaziers'.

Get some glass.

I was like, really?

He goes, yeah.

Shaun's got this pane of glass in his front door, and, uh, every time he goes out, he forgets his keys.

And so when he comes home, he just smashes the glass, reaches in and opens the door from the inside.

So I got this glazier bloke to cut me 20 panes.

And each time Shaun breaks it, I just fit a new one.

Anyway, we're down to the last one now.

So we kind of have to stop there.

So I thought, oh my God, what is this place gonna be like?

So we go to Shaun's.

♪ Son, I'm 30 ♪ We're doing this shoot that's like-- It's like a spoof Hello magazine shoot "At Home With".

♪ And I don't have a decent bone in me ♪ CHRIS FLOYD: Got on really great.

And then at the end, we finish, and he's like, do you want to stay the night?

Yes, it's all right.

I'll make the spare room up for you.

It'd really nice.

So that was it.

I stayed the night at Shaun Ryder's.

♪ Yippee-ippee-ey-ey-ay-yey-yey I had to crucify-- ♪ You know, the reality is, he's actually really sweet and lovely.

And he's really funny.

He's a talented wordsmith.

♪ So come on and say, yay ♪ Yes, I shot Paul McCartney for the cover of Q.

Going into that shoot, I knew exactly what they wanted, and that shot was Paul seated, holding his guitar, with the head of the guitar coming right at the viewer.

Before we really got into taking any photos, he said, come and look around, you know.

Look at different spaces.

We went upstairs, and he pulled out a double bass, which turned out to be Elvis Presley's bass.

And we just made him stood there, and he started to play Heartbreak Hotel on it and started singing it.

♪ Well, since my baby left me ♪ ♪ I found a new place to dwell ♪ ♪ It's down the end of Lonely Street ♪ ♪ It's Heartbreak Hotel ♪ ♪ And you'll be so lonely, baby ♪ ♪ You'll be so lonely ♪ ♪ You'll be so lonely, you could die ♪ ♪ Well, if you better leave him-- ♪ It was one of those moments where you just think, this is incredibly surreal.

I'm stood in Paul McCartney's studio, two feet away from him.

There's no one else here, and he's playing Heartbreak Hotel on Elvis's bass.

It's just this amazing moment that you find yourself in.

[bass slide] [applause] Then we went downstairs and did the shoot.

It was a wonderful experience.

[upbeat drum beat playing] I wanted to take a shot of the Stone Roses that would be remembered forever.

And I didn't feel I had a picture that told me what the Stone roses were about.

[rock music playing] I'd always felt because John Squire was so instrumental in the visuals of the band, in the way the sleeves worked and so on, I thought it would be an interesting idea to ask John to paint the band.

So that it was like this amorphous mass on the cover of paint and bodies.

But because John Squire's a Man United fan, I thought, I'm going to have sky blue and white paint for Man City.

I spent the morning turning the studio into a leak-free, polyethylene cube.

And I thought he'd get some brushes out and he'd spend ages painting the band.

The actuality was, he opened a gallon tin of paint and hurled it across the room, all over them.

And then picked the bottle, and tipped it over his own head, and lay in the shot.

And then they put the next color on, and he'd hurl that across the room, and pour it over himself, and get back in the shot.

And we did this for about two hours.

[rock music playing] I just let them do what they wanted, really.

If Ian wants to put his hands out or put a lemon in his mouth, or whatever he wants to do, then that sounds good, you know.

But my involvement is the shapes I'm getting on the composition of the shot.

They were desperate to shower this off.

And that's when I had to tell them there were no showers in the studio, so they had to go back to Ibrahim's flat, covered head to toe in paint.

Mani claims it didn't come out for about three weeks.

[rock music concludes] ANDY SAUNDERS: It's often been said that bands can't have a hit without radio, because you've got to be able to hear the music.

But equally, I don't think a band can have a career without press, because that photographic and that literary context that the magazine gives a band allows people to stop being just consumers of music and to become fans.

PHIL ALEXANDER: Kerrang is the only weekly that's left.

There is a reason for that.

One, the audience want it.

And B, the scene is actually still so active that we do have endless acts that we can put on the cover, be they brand new or more established.

[rock music playing] ♪ ♪ In the '80s, I got stereotyped as a heavy rock photographer.

That was mainly because I started a magazine called "Kerrang."

I never owned "Kerrang," but I was the main photographer.

And the idea was a guy called Jeff Barton, he was a writer, wanted to do an annual and call it Kerrang.

And it was things like Rainbow, Iron Maiden, and everybody laughed at him.

And the editors wouldn't let him.

So in the end, they agreed to do something called a oneshot, and a oneshot is a one-off cult magazine.

[heavy metal music playing] PHIL ALEXANDER: Ross Halfin did the first "Kerrang" cover.

I mean, obviously, it wasn't shot as a cover of a magazine.

It's just a perfect picture of Angus Young looking, you know, very Angus-like.

And I think it actually set up the aesthetic for what "Kerrang" actually became.

It encapsulates absolutely everything about what that type of music should be, you know.

You can see the sweat.

You can see the guitar.

It matches the name of the magazine, which is related, of course, to a power chord being hit.

And the whole thing about it, is it sets up where the magazine goes and continues to exist now.

I didn't even think it would do well, and it sold out overnight.

And that's how "Kerrang" was born, and they suddenly realized there was a market and this audience of kids that like heavy rock.

PHIL ALEXANDER: Ross gets these unbelievable photographs that no one else would really get, largely because of his relationship with artists.

These relationships stem back years.

Metallica wanted to shoot with Ross because he had done the inside sleeve of Iron Maiden's Live After Death, which has got probably 200 photographs of this ginormous iron maiden.

This thing continues right down the years.

You suddenly get a band like Ghost, who are going can we get Ross because he's the guy that did always Metallica things.

So you've kind of got this ongoing relationship, and it happens with every kind of classic photographer that is worth something and has defined a period.

And I think that's-- that's really prevalent with him.

My dad took me to see Iron Maiden when I was 12.

So heavy metal dominated my teenage years.

Long before I ever, ever contemplated being a photographer, my walls were plastered in photographs.

And I would genuinely guess that 99% of them-- I wouldn't be surprised if it was 100-- were Ross Halflin's photographs.

PHIL ALEXANDER: When we were working on the cover with "Kerrang," for instance, now what we're really looking for is that sense of kind of energy, that sense of the attitude that comes out of it, that basically is almost a raised middle finger in some cases.

Doesn't matter whether it's Ozzy, or Lars Ulrich, or endless Slipknot masks, right?

It's just about that sense of breathless excitement that exists within our audience, because they are genuinely excited about what is going on in the world.

[heavy metal music playing] At least the metal bands and the punk bands were giving you emotion.

They were giving you energy.

I mean, I worked at Melody Maker for 25 years.

I got a bit of a blind spot with the heavy metal, but fantastic photograph because of shapes, of course.

ALICE COOPER: There is this thing-- the invisible orange.

And it's this.

Every picture is this.

What is that?

[laughs] Is that Hamlet?

You know, is it a skull?

But every band is-- - [heavy metal music] - [camera clicking] They either want to be the devil or a viking.

And then you meet these guys that are like, hi.

My mom said to say hi, and she made these cookies for you.

And then they're on stage, and they're [growls] But, but I got to give them the credit.

They do a show.

[heavy metal music playing] You know, when I was growing up in Detroit, we had a magazine called Creem Magazine.

You know, kind of like a version of New Musical Express, or Melody Maker, that type of thing in the UK.

And it was those images that I saw in Creem magazine that I was sucked into.

They brought me in that situation, wherever it was happening.

It could be a photoshoot, but mostly, it was a live thing at that point in time that, of course, I was connected with.

Bowie and Ronson on stage.

The sexual energy there between them, even though there was no physical connection between the two of them, the way it was portrayed on stage was like he knew he was getting away with something.

He knew that he was creating that shock value.

I mean, at that time, there was nothing like that at all.

It was so shocking to see those pictures in Creem Magazine, you know.

But I was intrigued.

I was sucked into it.

ALICE COOPER: Creem was definitely my era.

In fact, I think Creem was more of a rock magazine than Rolling Stone, only because Rolling Stone had a political view, an agenda.

It was a rock magazine.

But it definitely had an agenda.

BOB GRUEN: Creem Magazine was a great magazine made by a bunch of kids who were fans, who just wanted to be involved in the music business.

And it was somewhat irreverent.

They followed bands like Kiss, Aerosmith, Alice Cooper, and Black Sabbath, bands that I liked a lot when I was, you know, 12, 13 years old.

You know, really hard rock.

And it was out of Detroit.

And so you'd see Iggy, MC5, or Bob Seger.

The guys that were real rockers were on the cover of Creem.

BOB GRUEN: Creem magazine took rock and roll more the way it was kind of meant to be taken, with a lot of fun.

Rock and roll's supposed to be fun.

And so Creem magazine would have fun with it.

[fast-paced jazz music] PHIL ALEXANDER: So what does the magazine cover do?

If you're an established artist, well, it continues that relationship with an audience that is key to you.

It's a complete affirmation of who they are, what they represent, and their status is confirmed.

JODI PECKMAN: Madonna became someone who was constantly on the cover because she kept having projects where she changed the way she looked, whereas someone like Bruce Springsteen, the covers are not that diverse.

A lot of times, they're very serious.

And he's not playing with the camera.

That's like the polar opposite of a Madonna cover.

There is one Bruce cover that he didn't like, and that's a picture where he's holding his guitar, and he's laughing.

And that is not a picture that he wants seen.

And he kept saying, I know what you're looking for.

I know what you want.

I know you want me to smile.

But I was so determined, and after having so many covers, he probably thought, I'll give them this one.

And I loved that picture, because to me, that was the real Bruce.

[musical accent] DANNY CLINCH: I had done a lot of hip-hop snd you know, people often will come with, you know, a party.

You know, they bring their whole crew.

They bring their friends.

They've got a barber.

When Danny Clinch photographed Tupac, Tupac was already a big star.

DANNY CLINCH: Tupac showed up with one other person.

And that surprised Danny, because a lot of hip-hop artists like do the entourage.

It's just part of what you get.

DANNY CLINCH: You can collaborate with people.

It can be something big, and conceptual, and fancy.

But it can also be something that's really subtle and intense.

And he had that subtlety, which I really admire.

Danny was photographing with a large format camera, which adds a certain gravitas to the exchange between photographer and subject.

I was shooting it for like a quarter page story.

And in the back of my mind, I was like, man, I'm, I'm shooting this from the cover.

Tupac was really interested in the camera, you know.

Because when Danny went behind it and put the focusing cloth over his head, it just made the moment like really, really elevated.

DANNY CLINCH: He really understood how to present himself.

And I think, you know, the camera loved him.

He had come prepared.

He had a bag full of clothes.

And so he took his shirt off to change into another shirt.

And I saw all his tattoos.

And he said, hey, let's just try a couple of photos of you like this.

You know, thug life, of course, which everyone knows.

But also, you know, the amazing like Nefertiti head over his chest.

And it turned out to be a really iconic photo.

And then after Tupac passed away, Rolling Stone then used that photo to commemorate him.

PHIL ALEXANDER: When you mark someone's passing with a magazine cover, what you're trying to say is remember them this way.

And that's what you really want out of that cover image.

In some cases, that means it's an absolutely classic image that people have seen a million times.

In other cases, it's purely an image that seems humanizing, and maybe isn't the iconic image.

It's the image that says, look, it's a real human being, because stardom strangely dehumanizes people.

And actually, sometimes, you just want to remember that this was a person that mattered.

ANDY SAUNDERS: If a great music icon dies, the fans are looking for a way to-- to not only reflect on that icon's life, but also to celebrate it.

And in the case of, say, Kurt Cobain, you know, very shocking that he killed himself.

And people were left with a lot of conflicting emotions.

Some of the amazing imagery that was used on the covers of music magazines allowed the fans of Kurt Cobain-- not only to reflect, and to be sad, and to mourn his loss-- but also to celebrate his life.

JODI PECKMAN: There's been many covers of Rolling Stone when people pass away.

They're usually headshots of the person, usually kind of a quiet contemplative photo.

And the only thing that goes on those covers is the date, the date they were born and the date they died.

It's very simple and it's just, you know, a tribute to the person.

Those covers do very well, unfortunately.

But they are interesting.

Even if people aren't a fan of the person, they read it and they get to know everything about them.

They're really moving covers.

In terms of Johnny Cash that cover we knew exactly what we wanted.

Mark Seliger had one of the most iconic images of Johnny Cash.

He'd photographed him many times.

But that came right to mind.

I mean, there was no question.

VIKKI TOBAK: These photos really memorialize a lot of artists.

Barron Claiborne's King of New York, that was the last photo that Biggie did in New York.

He actually left Barron Studio that day and got on a plane to go to LA, where he was killed shortly thereafter.

And that photo-- I mean, it was significant for many reasons.

One, Barron tells a story about how he, himself was a young black male.

And he did not want to create these cliché images of his fellow young Black men, who were making this music.

And so he always wanted to portray artists as royal, as having these really beautiful portraits of them done.

And so he wanted to photograph Biggie as a King, because he always said, you know, Biggie looked like a West African King to him.

Biggie was the King at the time.

I mean, this was at the height of his career.

He was King in New York.

He was King of hip hop at that moment.

And so Baron wanted to create a photo to match that, and it was meant to be for the cover of Rap Pages magazine.

That photo ironically almost didn't happen, because Diddy, who was guiding Biggie's career at the time, thought that he was going to look like Burger King if he took a photo in a crown.

Luckily, cooler heads prevailed, and it turned out to be an amazing photo.

But there is this one frame where Biggie is smiling, you know, a real Kool-Aid grin.

And everyone that knows or that knew Biggie, when they look at that photo, they say like, oh, that's the Big that we knew.

He had a great sense of humor.

He was always cracking jokes.

He was, you know, funny.

Funny as hell.

When you look at the totality of those photos, you really start to see the fuller human being.

You get to see a little bit of who they were behind the scenes and not just this final product that was made, even though that final product is a really quintessential photograph and maybe the most well known shot in hip-hop.

And that photo was carried through the funeral procession through Brooklyn when he was being laid to rest.

BRIAN CROSS: The tragedy is that they were both guys in their mid-20s.

And we don't think about Tupac as a guy in his mid-20s.

Both of those cats dying in a 12-month period is really profound impact on the culture.

The impact of street violence, taking away the two biggest stars of the culture, as they're about to really take hold of everything and change it, right at this moment, you know.

One album, two albums, and three albums in.

Obviously, Pac is extraordinarily prolific.

And there's many Tupac records after he's passed.

But, you know, at that moment, the world is just opening up to them.

That's super tragic, you know.

GERED MANKOWITZ: When David Bowie went, every music magazine carried a David Bowie cover.

But it was a massive celebration of that man's genius.

And how could anybody not put David Bowie on the cover in that moment?

We all had to.

The great photographers, through sheer force of personality, or charisma, or just great interpersonal skills, will be able to understand that the band don't really want to be there but create a bond with them that allows them to reach a shared outcome-- which is to make great art, to take great photographs.

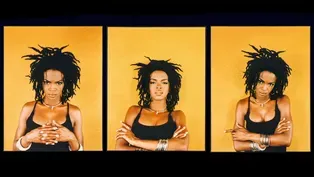

[hip hop music montage] She was quite late because she was at a photo shoot before that.

"I'm sorry, I'm four, five hours late."

I was like, you're here now.

We have a chance.

Like, cool, like I know how much, you know, the artists are doing and are going through in these critical moments of celebrating an album.

And this was her moment of Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

It was Honey Magazine.

They were starting a magazine, and they wanted to really like lean in.

They got her.

She was a perfect fit, and I was like, I'm going to play into the honey tones, you know.

The different sort of degrees.

She was six months pregnant, and she was glowing, man.

I mean, she must have felt just like on top of the world, like just floating along.

There was a mirror on set that was sort of off camera.

And she would be looking off to her right.

And she'd give the most amazing look, and then look back to me, and it was gone.

She'd do it again and just get perfect, and then look back to me, it was gone.

And I was like, you got to share some of those looks.

So the dynamic was how to do this dance to make her comfortable with how she was appearing to herself.

So I said, let's try this.

And so I took the mirror, and I shot with a mirror under my chest.

Full length mirror, so it could just be a look down, and then I look up, and then it wasn't lost.

For the cover, we ended up-- there was just like a little roundness that sort of looked kind of like a belly, but not fully pregnant, and not really embracing it.

And I was like, you know, I just wanted to be focused on her rather than the moment of being pregnant.

And so we just retouched a little bit of the belly back in, so it just kind of wasn't a distraction from her, you know-- even though certainly, it was Zion in her belly, which became part of the song, which became part of the album, which-- you know.

I mean, it's a major, major moment.

And to look back and now, like to have captured the two of them in that moment, [accent] special, man.

[rock guitar accent] CHRIS CHARLESWORTH: There was a golden era for rock photographers.

They were in the fortunate position of being able to take iconic shots when access was easy.

I don't think today's photographers in their 20s have that luck.

So I got a call to go to the Bottom Line to shoot this new guy, and to shoot concert shots of him.

And I'm like, great.

That sounds good.

Then he says to me, yeah, and we'd also like you to get some backstage shots.

And now I'm completely panicked, because he's asking me to go and get my own permission.

And I was sick to my stomach that I had to do that.

But I pushed myself to go backstage.

And a really large man came to the door, and I'm sure, in a very high-pitched voice, said that I was from the Soho Weekly News, and they've asked that I get a backstage picture.

And he said, yeah, Prince doesn't do that.

And then I said, OK, thank you very much.

And I was so relieved, because I didn't think I would have done a good job anyway.

And I went back to get in position.

The opening act comes on.

I shoot a few frames, and then I get a tap on my shoulder, and that same man asks me to follow him.

We walk backstage, and he says, since you were so nice about that, come on in and take a few shots.

[music playing] That person who let me in knew that when I went in there, I would not be disruptive to him.

He knew it.

And I don't know who was more shy, he or me.

But I believe that that was him completely-- shy, not very comfortable, but really sweet, too, in a very quiet, quiet way.

I didn't even shoot a full roll of film.

And then I looked at him, and I asked if he'd like to take a picture of me.

So I have a picture of me by Prince.

Although I missed a lot of opportunities by being shy, by being too polite, by not being pushy, by not saying, oh, man, please.

Like, if I don't get-- you know.

I could never do that.

So I missed things.

But then I gained some things by just being who I was.

A lot of photographers tell me how it was hard for them in the beginning to even sell their photos to anyone, because none of the mainstream music magazines even wanted to publish photos of hip-hop.

So they were taking these photos, but they had nowhere to sell them.

And so that gave rise to this great movement of hip-hop journalism and magazines you started to see be borne out of need, really.

So you had Rap Pages.

You had Ego Trip, Stress magazine, a lot of indies that were being published a lot of times by like young bootstrap, you know, entrepreneurs, who were same age as the people that they were covering.

Brian was actually the photo editor of Rap Pages and did a lot of those iconic covers, Goodie Mob, even the ODB one, which is a personal favorite.

♪ I'm the one-man army, Ason ♪ ♪ I never been tooken out ♪ ♪ I keep MCs looking out ♪ BRIAN CROSS: ODB was hot, you know.

This is one of the first solo members of the Wu.

Brooklyn Zoo was the hot single.

Everybody was hyped on it.

And he was going to play at Glam Slam, which is Prince's club in downtown.

And I remember going, and of course, he was two hours late.

[laughing] Of course.

And then he comes out, takes his pants down, he stands there in his boxer shorts, assumes the John Travolta pose from the poster of Saturday Night Fever, and sings Somewhere Over the Rainbow.

And it was like, people were not ready for that.

I mean, that level of dada, you know what I mean?

Like I remember somebody saying, he's really free.

He's really free.

There's no script for this, you know.

And so that's ODB.

So it's chaos, you know.

But that's why also I love your story so much of your Rap Pages cover, which was, of course, a recreation of the Patrick Demarchelier Rolling Stone cover with Janet Jackson.

You know, as B+ tells it, like they were sitting around the Rap Pages offices, and kind of joking, and laughing about... BRIAN CROSS: Whose hands-- in the Janet photo, whose-- whose hands were they?

[camera clicks] Think it was Gabe, Gabe Alvarez says, man, it's ODB's hands.

Of course, it is.

And that was like the funniest thing all day.

And so we were like, that's it.

We should do that.

♪ Shame on you when you step through ♪ ♪ To The 'Ol Dirty Bastard, Brooklyn Zoo ♪ BRIAN CROSS: We're in this little studio in Manhattan, and here comes this girl that looks like Janet Jackson we've cast.

And here he comes, and when it really comes to the moment-- first off, he don't want anybody else in the room, he says besides me, and the model, and him.

And then the second part is, once it really come down to where you have to put his hands on this woman's breasts, he suddenly, he's just a regular human being, who's very nervous, and was like, OK, OK, OK. OK, just give me a second here.

Let me just prepare myself for this.

We shot two or three rolls, and he ran off.

That was it.

He didn't even say goodbye to me.

He pulled an Irish goodbye.

He was just like, ta!

ANDY SAUNDERS: Hey listen, sex sells.

It sells in advertising.

It sells in films.

So why wouldn't music magazines use sex to sell?

JODI PECKMAN: As a photo director and an art director, I produce a lot of sexy covers.

I'm not afraid to admit that.

I don't think there's anything wrong with that.

I've gotten some slack for it, because I do it more often than not.

But they draw a reader in, and you see those covers on a newsstand.

They're usually very attractive and provocative on any magazine.

It's something that's really popular.

So I don't think it's a bad thing necessarily, even though I've been told it's a bad thing.

And generally, it's more women that are sexy.

But certainly Rolling Stone has had a lot of men on the cover without their shirts on.

[camera clicks] The Red Hot Chili Peppers, I hadn't been art directing many covers before that.

So of course, I was nervous.

The original idea from the photographer was to paint them red as a reference to a chili pepper.

We got there and they would have no part in it.

It was not going well for me.

So I went in the other room to call my editor, you know.

I'm not sure what to do in this situation.

These guys are super difficult.

It was about a 3-minute conversation.

And I went back into the studio, and I saw the guys putting their clothes back on.

And the photographer showed me a Polaroid, and it was the guys standing there, naked, covering themselves.

[Red Hot Chili Peppers music playing] I was so relieved when I saw that picture.

I knew right away it was going to be a memorable iconic moment.

I had really no part in it, but I still get some credit for it, because I was there, and, you know, that's how those things happen.

ANDY SAUNDERS: Probably from the '70s to the early 2000s, they were the glory years of music magazines.

And of course, I was working with bands, and I was helping them be on the covers.

There was nothing like it.

There was no buzz like seeing your band that you had sold into that magazine, grabbing that magazine off a newsstand, and seeing it.

I still get goose bumps thinking about it.

MARK WAGSTAFF: There's always going to be a room for music magazines celebrating great artists and great photography, you know.

People have a hunger for it.

And if you present it in an impactful-enough way, then I think there's always going to be an appreciation.

I don't think that's ever going to go away.

ART ALEXAKIS: Iconic images are still very important.

But I don't think being in a magazine is what it was at one time.

I think you can do things in social media and online that are just as important and have as much impact as magazines and print media does, unfortunately.

[theme music playing]

Episode 4 Preview | On the Cover

Video has Closed Captions

Music magazines played a pivotal role in elevating music photography to iconic status. (31s)

Video has Closed Captions

Photographer Jonathan Mannion shoots Lauryn Hill for Honey Magazine. (1m 49s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship