The River Styx (January 1964-December 1965)

Episode 3 | 1h 57m 55sVideo has Audio Description

With South Vietnam near collapse, LBJ bombs the North and sends US troops to the South.

With South Vietnam in chaos, hardliners in Hanoi seize the initiative and send combat troops to the south, accelerating the insurgency. Fearing Saigon’s collapse, President Johnson escalates America’s military commitment, authorizing sustained bombing of the north and deploying ground troops in the south.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for The Vietnam War is provided by Bank of America; Corporation for Public Broadcasting; David H. Koch; The Blavatnik Family Foundation; Park Foundation; The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations; The...

The River Styx (January 1964-December 1965)

Episode 3 | 1h 57m 55sVideo has Audio Description

With South Vietnam in chaos, hardliners in Hanoi seize the initiative and send combat troops to the south, accelerating the insurgency. Fearing Saigon’s collapse, President Johnson escalates America’s military commitment, authorizing sustained bombing of the north and deploying ground troops in the south.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The Vietnam War

The Vietnam War is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Vietnam Stories

We asked viewers to share their experiences during the events of the Vietnam War era. The response was thousands of videos, photographs, and short stories.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

These episodes feature audio tracks containing English, Spanish and Descriptive Audio.

The Weight of Memory (March 1973-Onward)

Video has Audio Description

Saigon falls and the war ends. Americans & Vietnamese from all sides seek reconciliation. (1h 50m 56s)

The Veneer of Civilization (June 1968-May 1969)

Video has Audio Description

After chaos roils the Democratic Convention, Nixon, promising peace, wins the presidency. (1h 50m 54s)

This Is What We Do (July 1967-December 1967)

Video has Audio Description

President Johnson escalates the war while promising the public that victory is in sight. (1h 28m 17s)

Things Fall Apart (January 1968-July 1968)

Video has Audio Description

Shaken by the Tet Offensive, assassinations and unrest, America seems to be coming apart. (1h 27m 46s)

Video has Audio Description

As a communist insurgency gains strength, JFK wrestles with US involvement in Vietnam. (1h 26m 27s)

Resolve (January 1966-June 1967)

Video has Audio Description

US soldiers discover Vietnam is unlike their fathers’ war, as the antiwar movement grows. (1h 57m 25s)

The History of the World (April 1969-May 1970)

Video has Audio Description

Nixon withdraws troops but upon sending forces to Cambodia the antiwar movement reignites. (1h 52m 9s)

A Disrespectful Loyalty (May 1970-March 1973)

Video has Audio Description

South Vietnam fights alone as Nixon and Kissinger find a way out for America. POWs return. (1h 52m 32s)

Video has Audio Description

After a century of French occupation, Vietnam emerges independent but divided. (1h 25m 20s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANNOUNCER: MAJOR SUPPORT FOR "THE VIETNAM WAR" WAS PROVIDED BY MEMBERS OF THE BETTER ANGELS SOCIETY, INCLUDING JONATHAN AND JEANNIE LAVINE, DIANE AND HAL BRIERLEY, AMY AND DAVID ABRAMS, JOHN AND CATHERINE DEBS, THE FULLERTON FAMILY CHARITABLE FUND, THE MONTRONE FAMILY, LYNDA AND STEWART RESNICK, THE PERRY AND DONNA GOLKIN FAMILY FOUNDATION, THE LYNCH FOUNDATION, THE ROGER AND ROSEMARY ENRICO FOUNDATION, AND BY THESE ADDITIONAL FUNDERS.

MAJOR FUNDING WAS ALSO PROVIDED BY DAVID H. KOCH...

THE BLAVATNIK FAMILY FOUNDATION...

THE PARK FOUNDATION, THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES, THE PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS, THE JOHN S. AND JAMES L. KNIGHT FOUNDATION, THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION, THE ARTHUR VINING DAVIS FOUNDATIONS, THE FORD FOUNDATION JUSTFILMS, BY THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING, AND BY VIEWERS LIKE YOU.

THANK YOU.

Announcer: Can looking back push us forward?

Man: Ladies and gentlemen, Miss Billie Holiday.

♪ Will our voice be heard through time?

Can our past inspire our future?

...act of concern... ♪ Bank of America supports filmmakers like Ken Burns, whose narratives illuminate new perspectives.

What would you like the power to do?

Bank of America.

(birds chirping, dog barking in distance) ("With God on Our Side" by Bob Dylan playing) DYLAN: ♪ Oh, my name, it ain't nothin' ♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: Well, I wanted to name him after his dad, Denton Winslow Crocker.

So that was the name we chose.

He was a colicky little baby.

And, uh, so we were up night and day with him.

And my husband was a wonderful dad and very loving and attentive.

He'd walk the floor with him.

And then he said one day, "He's a regular little mogul the way he rules our lives."

So that's where the name came from.

We called him Mogie.

NARRATOR: Mogie Crocker was born June 3, 1947, the oldest of four children.

His father was a biology teacher, and Mogie was raised in college towns: Ithaca, Amherst, and finally Saratoga Springs, to which the family moved in 1960, when he was 13.

My mother read books to all of us.

My brother was definitely the one who probably gravitated towards them more than I did.

He really feasted on books.

NARRATOR: Mogie was an unusual boy.

Intelligent, independent-minded, and too nearsighted to do well at team sports, he loved books about American history and American heroes.

At 12, he started a diary in which he kept track of Cold War events.

"I hate Reds!"

he wrote, and he admired most those who had proved willing to sacrifice themselves for a cause.

President John F. Kennedy's call for every American to ask what he or she could do for their country had mirrored ideas he'd held since he was a small boy.

One evening when I was reading to Denton before he went to sleep, I chose a passage from Henry V, which is, "He today that sheds his blood with me "shall be my brother.

"And gentlemen in England now a-bed "shall think themselves accurs'd "they were not here and hold their manhood cheap while any speaks that fought with us upon St. Crispin's Day."

(distant bombs echoing) DYLAN: ♪ If another war comes... ♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: I think that it was that sort of thing that made Denton want to be part of something important and brave.

DYLAN: ♪ With God on their side.

♪ ("With God on Our Side" continues) LYNDON JOHNSON: I just stayed awake last night thinking about this thing.

The more I think of it, I don't know what in the hell... it looks like to me we're getting into another Korea.

It just worries the hell out of me.

I don't see what we can ever hope to get out of there with once we're committed.

I don't think it's worth fighting for and I don't think we can get out.

And it's just the biggest damn mess I ever saw.

McGEORGE BUNDY: It is, it's an awful mess.

JOHNSON: I just thought about ordering those kids in there, and what in the hell am I ordering them out there for?

BUNDY: One thing that has occurred to me... JOHNSON: What the hell is Vietnam worth to me?

What is it worth to this country?

BUNDY: Yeah, yeah.

JOHNSON: Now, of course, if you start running the communists, they may just chase you right into your own kitchen.

BUNDY: Yeah.

That's the trouble.

And that is what the rest of that half of the world is going to think if this thing comes apart on us.

LYNDON JOHNSON: It's damned easy to get in a war, but it's going to be awfully hard to ever extricate yourself if you get in.

BUNDY: It's very easy... JOHNSON: I'd like to hear Walter and McNamara to evaluate this thing.

BUNDY: To debate it?

JOHNSON: Yeah.

BUNDY: All right, what's a possible time...?

NARRATOR: Tragedy had brought Lyndon Johnson to the presidency in November of 1963.

And he would not feel himself fully in charge until he had faced the voters the following year.

But his ambitions for his country were as great as those of his hero, Franklin Roosevelt.

During his years in the White House, he would lead the struggle to win passage of more than 200 important pieces of legislation-- the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, federal aid to education, Head Start, Medicare, and a whole series of bills aimed at ending poverty in America, all intended to create what he called "The Great Society."

In foreign affairs, Johnson was less self-assured.

"Foreigners are not like the folks I'm used to," he once said.

To deal with them, he retained in office all of John Kennedy's top advisors-- Dean Rusk at State, Robert McNamara at Defense, McGeorge Bundy as his National Security Advisor.

"I need you," he told them, more than his predecessor had.

Publicly, Johnson pledged that "This nation will keep its commitments from South Vietnam to West Berlin."

But privately, Vietnam filled him with dread.

"It's going to be hell in a handbasket out there," his ambassador told him.

"I want the South Vietnamese to get off their butts "and get out into those jungles and whip the hell out of some communists," the president said.

"And then I want 'em to leave me alone, "because I've got some bigger things to do right here at home."

Johnson had opposed the military coup that had overthrown and murdered South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem, fearing it would make a bad situation worse.

It had.

(gunfire, shouting) The National Liberation Front-- the Viet Cong-- was making coordinated attacks throughout the countryside, some 400 of them in just two weeks.

NARRATOR: An estimated 40% of the South Vietnamese countryside, and more than 50% of the people, were effectively in the hands of the Viet Cong.

And the Vietnamese generals who had overthrown Ngo Dinh Diem were bickering among themselves.

The assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem set in motion a series of coups.

Each government was less effective than the one before.

NARRATOR: In January 1964, with U.S. encouragement, General Nguyen Khanh staged yet another coup.

In March, Johnson sent McNamara to Vietnam with instructions to show the people that Khanh was "our boy."

SAM WILSON: Johnson said, "Let's get him out and get him speaking to people, "and let McNamara go with him as well "so that people can see that the United States is solidly behind this man."

We fully support the people of South Vietnam.

BUI DIEM (speaking English): When Khanh gave a tedious, long, laborious speech ending up with, "Vietnam (speaking Vietnamese), Vietnam (speaking Vietnamese), Vietnam a thousand years."

McNamara leaned over to the microphone and said... (attempting to repeat Vietnamese phrase) BUI DIEM: (McNamara attempting to repeat Vietnamese phrase) What he was saying was something like, "The little duck, he wants to lie down."

(attempting to repeat Vietnamese phrase) WILSON: He wasn't aware of the tonal difference.

And McNamara grabbed one fist and held them up.

And the crowd practically disintegrated on the cobblestones.

NARRATOR: "No more of this coup shit," President Johnson told his advisors.

But Khanh, too, lacked popular legitimacy, and other generals continued to jockey for power.

Washington turned a deaf ear to Buddhist calls for the genuinely representative government they'd hoped they'd get when Diem was overthrown.

Between January 1964 and June of 1965, there would be eight different governments.

All of their leaders were so close to the Americans that they were seen as puppets.

(shouting, whistling) One weary Johnson aide suggested that the national symbol of South Vietnam should be a turnstile.

MURRAY FROMSON: These demonstrating students seem to symbolize the kind of anarchy that is descending on Saigon these days.

This kind of political backbiting is having serious consequences in the countryside, for until a strong government begins to function here in Saigon, the war against the communists will continue to founder.

DONG SI NGUYEN: NARRATOR: Ho Chi Minh was still a beloved figure in North Vietnam, still concerned that his country remained fragile, still wary that stepping up the conflict in the South might force the Americans to take a still more active role.

But Ho now shared power with younger, more impatient leaders.

There had been change and turmoil in North Vietnam, too, just as there had been in Saigon and Washington, though Americans knew almost nothing about it.

HUY DUC: NARRATOR: At the Ninth Party Plenum that began in Hanoi on November 22, 1963, the day President Kennedy was killed in Dallas, the Politburo had argued over how best to proceed in the war.

North Vietnam's two communist patrons, the Soviet Union and China, were giving them conflicting advice.

NGUYEN NGOC: NARRATOR: In two weeks of sometimes bitter debate, Ho Chi Minh, who favored the Soviet strategy, was outmaneuvered by party First Secretary Le Duan, who sided with the Chinese.

NGUYEN NGOC: NARRATOR: Le Duan believed that with Diem gone, and the Saigon government in disarray, it was time to move quickly in 1964.

He proposed a two-phase plan for victory in South Vietnam.

The first phase would destroy ARVN forces through big, "decisive battles"; the second, an attack on the cities, Le Duan believed, would then set off popular revolts within them.

Party leaders and others suspected of having opposed the plan were denounced as "revisionists," demoted, dismissed, imprisoned.

Hundreds were sent to "re-education camps."

"Uncle Ho wavers," Le Duan said, "but I have only one goal-- final victory."

WOMAN: Secretary McNamara on line 0.

JOHNSON: Bob?

McNAMARA: Yes, Mr. President?

JOHNSON: I hate to bother you, but... McNAMARA: No trouble at all.

JOHNSON: Tell me, have we got anybody that's got a military mind that can give us some military plans for winning that war?

Let's get some more of something, my friend, because I'm going to have a heart attack if you don't get me something.

We need somebody over there that can get us some better plans than we got, because what we got is what we've had since '54.

We're not getting it done.

We're-we're losing.

McNAMARA: Well, it's one reason I want to go back.

Kick 'em in the tail a little bit will help here at this point.

JOHNSON: Yeah.

What I want is somebody to lay up some plans to trap these guys and whup hell out of 'em.

Kill some of 'em.

That's what I want to do.

McNAMARA: I'll try and bring something back that will meet that objective.

JOHNSON: Okay, Bob.

McNAMARA: Thank you.

(phone hangs up) NARRATOR: When his counselors urged him to do so, Johnson increased the number of American military personnel from 16,000 to more than 23,000 by the end of the year.

But he wanted his own team in Saigon.

He replaced Henry Cabot Lodge, making General Maxwell Taylor his ambassador, and selected 49-year-old General William Westmoreland, a decorated commander from WWII and Korea, to lead the American military effort.

The president hoped to force Hanoi to abandon its support for the guerrilla struggle in the South by gradually escalating military pressure.

He authorized American pilots to bomb North Vietnamese troops and installations in the neighboring country of Laos.

And he directed the military to oversee South Vietnamese shelling of North Vietnamese islands and raids on coastal bases.

All of it was to be conducted in secret.

The American people were not to be told.

It was an election year.

Meanwhile, the Joint Chiefs of Staff felt strongly that the United States was fighting on the enemy's terms and urged far more drastic and dramatic action-- air strikes against "critical targets" in North Vietnam itself and the deployment of U.S. forces in South Vietnam-- boots on the ground.

Johnson refused, fearing that such aggressive moves would pull China into the conflict just as it had entered the Korean War in 1950.

JOHNSON: They say get in or get out.

McGEORGE BUNDY: Yeah.

JOHNSON: And I told them, we haven't got any Congress that will go with us, and we haven't got any mothers that will go with us in the war, and I got to win an election and then you can make a decision.

(crowd cheering) NARRATOR: Polls showed him with a commanding lead over his likely Republican opponent, Senator Barry F. Goldwater of Arizona, a blunt, uncompromising critic of what he charged was the administration's weakness in the face of communist aggression.

BARRY GOLDWATER: Why does he put off facing the question of what to do about Vietnam?

Does he hope that he can wait until after the election to confront the American public with the... BILL EHRHART: Here were these communists who were overrunning Southeast Asia and Johnson's doing nothing about it.

My opponent has not told you what he plans to do about the Cold War.

I rode around the back of a flatbed truck in Perkasie with a bunch of my classmates singing Barry Goldwater campaign songs because Lyndon Johnson was not tough enough on those communists.

NARRATOR: Johnson felt he did not yet have the political capital to take further action in Vietnam, but he asked his aide, William Bundy, to draft a Congressional resolution authorizing him to use force if needed to be sent to Capitol Hill when the time was right.

On July 30, 1964, South Vietnamese ships under the direction of the U.S. military shelled two North Vietnamese islands in the Gulf of Tonkin.

The tiny North Vietnamese Navy was put on high alert.

What followed was one of the most controversial and consequential events in American history.

On the afternoon of August 2, the destroyer U.S.S.

Maddox was moving slowly through international waters in the gulf on an intelligence-gathering mission in support of further South Vietnamese action against the North.

The commander of a North Vietnamese torpedo-boat squadron moved to attack the Maddox.

The Americans opened fire and missed.

North Vietnamese torpedoes also missed.

But carrier-based U.S. planes damaged two of the North Vietnamese boats and left a third dead in the water.

Ho Chi Minh was shocked to hear of his navy's attack and demanded to know who had ordered it.

The officer on duty was officially reprimanded for impulsiveness.

No one may ever know who gave the order to attack.

To this day, even the Vietnamese cannot agree.

But some believe it was Le Duan.

HUY DUC: NARRATOR: Back in Washington, the Joint Chiefs urged immediate retaliation against North Vietnam.

The president refused.

Instead, the White House issued a warning about the "grave consequences" that would follow what it called "any further unprovoked" attacks-- even though Johnson knew the attack had been provoked by the South Vietnamese raids on North Vietnam's islands.

Both sides were playing a dangerous game.

On August 4, American radio operators mistranslated North Vietnamese radio traffic and concluded a new military operation was imminent.

Actually, Hanoi had simply called upon torpedo boat commanders to be ready for a new raid by the South Vietnamese.

The Maddox and another destroyer, the Turner Joy, braced for a fresh attack.

So did the White House.

LYNDON JOHNSON: Go ahead, Mac.

McNAMARA: I-I personally would recommend to you, after a second attack on our ships, that we do retaliate against the coast of North Vietnam some way or other... JOHNSON: What I was thinking about when I was eating breakfast: when they move on us and they shoot at us, I think we not only ought to shoot at them, but almost simultaneously pull one of these things that you've been doing on one of their bridges or something.

McNAMARA: Exactly.

I quite agree with you, Mr. President.

JOHNSON: But I wish we could have something that we've already picked out, and just hit about three of them damn quick, right after.

NARRATOR: No second attack ever happened, but at the time, anxious American sonar operators aboard the Maddox and Turner Joy convinced themselves one had.

The attack was probable but not certain, Johnson was told, and since it had probably occurred, the president decided it should not go unanswered.

JOHNSON: Aggression by terror against the peaceful villagers of South Vietnam has now been joined by open aggression on the high seas against the United States of America.

Yet our response, for the present, will be limited and fitting.

We Americans know, although others appear to forget, the risk of spreading conflict.

We still seek no wider war.

EVERETT ALVAREZ: If that came to be where we would be called upon to carry out our responsibilities, and having been well trained for this, I never really gave it much thought.

It was part of my duty.

NARRATOR: Lieutenant Everett Alvarez from Salinas, California, was aboard the U.S.S.

carrier Constellation.

His squadron of Skyhawk A-4 planes was ordered to attack torpedo boat installations and oil facilities near the port of Hon Gai.

For the first time, American pilots were going to drop bombs on North Vietnam.

ALVAREZ: When we approached the target coming down from altitude, it was obvious that they could pick us up on their radar.

I remember my knees shaking.

And I was saying, "Holy smokes, I'm going into war."

"This is war."

I was a bit scared.

Once we went in and they started firing at us, the fear went away.

Everything became smooth, deathly quiet in the cockpit.

It was sort of like a symphony in the sense that my plane was just like a ballet in the sky, and I was just performing what I was doing.

And then I got hit.

MAN: Mayday, Mayday.

(instruments beeping) NARRATOR: Coastal militiamen captured Alvarez and turned him over to the North Vietnamese military.

ALVAREZ: One fella was yelling at me in Vietnamese and saying something.

I started talking to him in Spanish.

Don't ask me why.

It seemed like a good idea at the time.

After when they discovered U.S.A. on my ID card and then they started speaking to me in English.

NARRATOR: Alvarez assumed he would be treated as a prisoner of war.

ALVAREZ: I was sticking to the code of conduct, which is giving them name, rank, service number, and date of birth.

But they quickly reminded me that there was no state of war, no declaration of war.

So I could not be considered a prisoner of war.

I recall thinking about it, and I says, "You know what?

They're right."

NARRATOR: Everett Alvarez was the first American airman to be shot out of the sky over North Vietnam and the first to be imprisoned there.

Now, the president sent up to Capitol Hill the resolution he had asked his aide William Bundy to draft two months earlier.

JAMES WILLBANKS: Johnson is sort of prepositioned to move anyway, and it gives him really the incident that he needs to go to Congress and ask for a resolution that will allow him to deal with what he sees as aggression in Vietnam.

And what he gets is the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which is, what he says, like "Grandma's nightshirt"-- it covers everything.

I think what Johnson is looking for is the opportunity, the right time to send a message to North Vietnam that we're serious about supporting South Vietnam.

That message is sent, I think we misread the enemy because they're just as serious as we are.

NARRATOR: On August 7, 1964, by a vote of 88-2, the Senate passed what came to be called the Tonkin Gulf Resolution.

In the House, not a single congressman opposed it.

Senator Goldwater could no longer plausibly claim Johnson was failing to fight back against North Vietnam, while those voters concerned that the United States was in danger of becoming too deeply involved admired the president's measured response.

Support for Johnson's handling of the war jumped overnight from 42% to 72%.

The American public believed their president.

Le Duan and his comrades in Hanoi did not.

They had little faith in the president's claim that he sought no wider war.

They resolved to step up their efforts to win the struggle in the South before the United States escalated its presence by sending in combat troops.

For the first time, Hanoi began sending North Vietnamese regulars into the South, down the network of paths they had hacked out of the Laotian jungle-- the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

PETER KALISCHER: This is Bien Hoa Air Base, the biggest in South Vietnam, hours after being hit by a communist mortar barrage.

NARRATOR: On November 1, Viet Cong guerrillas shelled the American airbase at Bien Hoa near Saigon.

Five Americans died.

Thirty were wounded.

Five B-57 bombers were destroyed on the ground and 15 more were damaged.

PETER KALISCHER: Mr.

Ambassador, do you think this shows any new capability that they've got, the Viet Cong?

Uh, I would simply say they've never done this before.

NARRATOR: The Joint Chiefs advised the president to mount an immediate all-out air attack on 94 targets in the North and to send in regular Army and Marine units-- not more advisors-- to South Vietnam as well.

He would not do it.

The election was just two days away.

Lyndon Baines Johnson won the presidency in his own right, and he won it by a landslide.

Within a month, the president would approve what was called a "graduated response"-- limited air attacks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and "tit for tat" retaliatory raids on North Vietnamese targets.

But he refused to undertake sustained bombing of the North until the South Vietnamese got their own house in order.

In private, Johnson doubted that airpower alone would ever work and believed that he would eventually have to send in ground troops, though he was not yet willing publicly to say so.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: In the fall of '64, Denton was 17 and he was determined to go into the service.

NARRATOR: Mogie Crocker had been restless since the summer.

After the Gulf of Tonkin incident, he had confided to his sister that he wanted to join the Navy, but he knew his parents would not sign the consent form that would have allowed a 17-year-old to enlist.

He was talking about wanting to go into the service and that his attempts to go underage had failed.

And that he wanted my parents to support him in that.

NARRATOR: His parents tried to persuade him that he could be more useful to his country with a college education than as just another private.

Mogie was adamant.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: Monday morning he left for school.

And I watched him leave.

But that night he didn't come in for supper and he hadn't called.

The day that my brother ran away has to be one of the most bizarre experiences in my life.

I eventually happened to look in my piggy bank and he had taken the money I had and left a note for me.

He had promised he would pay me back.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: He was gone about four months and said that he would not come home unless we agreed to sign for him.

And he wouldn't be 18 until June.

But we did agree and he did come home.

My husband felt it was an honor-bound agreement.

I was hoping that I could change his mind.

("The Marines' Hymn" plays) PHILIP BRADY: To my mind, the Marine Corps represented the very best.

And it does.

They are the best.

And I wanted to be part of the best.

I was competitive.

I was pugnacious.

But I wanted to get in the Marine Corps and go to the first war I could find.

NARRATOR: Lieutenant Philip Brady, from Port Washington, New York, arrived in Saigon just a few days after Lyndon Johnson's election, one of the new advisors sent to help shore up the South Vietnamese military.

We must ensure that women and children are not injured.

NARRATOR: General Westmoreland himself greeted the newcomers.

He was an impressive-looking man with an impressive record.

Many of the men he'd led in Tunisia, Sicily, and Normandy during World War II called him Superman.

He'd fought with distinction in Korea, commanded the 101st Airborne, served as superintendent of West Point.

TIME magazine called him "the sinewy personification of the American fighting man."

But at the same time, win the hearts and the minds of the people.

BRADY: General Westmoreland told us that we were down on the five-yard line and we just needed a few more to go get the touchdown.

Then I went out and then I got on the ground.

And then I found out, "Don't you realize?

We're losing this war."

NARRATOR: Lieutenant Brady was assigned to assist Captain Frank Eller, senior advisor to the 4th Battalion of the Vietnamese Marine Corps, an elite unit whose members called themselves the "Killer Sharks."

You were told that you were going over there to guide, educate, and elevate essentially these "little fellas" on how to fight a war when, in fact, they knew exactly how to fight the war.

You were just an appendage.

You were there simply to guide assets that they didn't have: American artillery, American air strikes.

NARRATOR: Brady did his best to get to know the South Vietnamese marines in his unit.

TRAN NGOC TOAN (speaking English): NARRATOR: Lieutenant Tran Ngoc Toan, the son of a trucker, had escaped life with a hostile stepmother by entering the South Vietnamese Military Academy at Dalat.

He'd been fighting the Viet Cong for more than two years.

Toan was one of the junior officers.

I think he was a...

I think he was a company commander.

I knew him, I liked him.

He was a Dalat graduate, which is like their West Point.

Very dedicated.

NARRATOR: Brady, Toan, and the 4th South Vietnamese Marine Battalion were stationed near the Bien Hoa Airbase in reserve, waiting to be called into action.

There were new rumors now, of larger enemy units moving through the countryside.

Le Duan's plan to win a quick and decisive victory was underway.

NGUYEN VAN TONG: NARRATOR: Nguyen Van Tong was a political officer in the newly created Viet Cong 9th Division, one of perhaps 2,000 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops who had for weeks been quietly filtering into Phuoc Tuy, a supposedly "pacified" province less than 40 miles southeast of Saigon.

NGUYEN VAN TONG: NARRATOR: The target for Tong and his comrades was the strategic hamlet of Binh Gia, home to some 6,000 Catholic anticommunist refugees.

Their plan was to seize the hamlet and then annihilate the forces Saigon was sure to send to retake it.

To ensure success, tons of heavy weapons were smuggled onto the coast under cover of darkness-- mortars, machine guns, recoilless rifles capable of blasting tanks.

The communists had never attempted anything on this scale before.

Before dawn on December 28, Viet Cong advance units easily overwhelmed the village militia and occupied Binh Gia.

(shouting, gunfire) When two crack South Vietnamese Ranger companies were helicoptered in the next day, they were ambushed and shot to pieces.

On the morning of the 30th, Philip Brady, his friend Tran Ngoc Toan, and the 4th Marine Battalion were flown in to relieve and reinforce the Rangers.

The enemy withdrew east of the village.

NGUYEN VAN TONG: All of a sudden you could see the tracers come out of the plantation, hit the helicopter, it crashed.

We were ordered to go down and retrieve the remains the following morning.

NGUYEN VAN TONG: BRADY: The lead company got to the remains and then was pounced on and mauled badly.

(gunfire) NARRATOR: Twelve South Vietnamese Marines from Toan's unit were killed getting to the downed helicopter.

Their comrades wrapped them in ponchos and laid them out next to the dead Americans.

An American chopper dropped into the clearing.

The American crew jumped out under fire, picked up the four Americans, climbed back into their chopper, and took off again.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: NARRATOR: For three hours, Toan and his men stayed with their own dead waiting for a helicopter to carry them off the battlefield.

BRADY: Meanwhile, I am getting a little bit antsy because, first of all, we're losing light.

Second of all, we are now outside of artillery range.

We've got to get out of there.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: BRADY: I went to the Major Nho, his name was, and I said, "Major, we have to get out of here now."

And Nho said, "Don't you forget I am a major, and you are a lieutenant," turned on his heel and walked away.

Ten minutes later all hell broke loose.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: (man shouts in Vietnamese) NARRATOR: The shelling eventually died down.

But then bugles blew, and wave after wave of enemy troops advanced toward the badly outnumbered men.

BRADY: It was as if you turned a soundtrack of shooting... And just went (imitates rapid gunfire).

Just like that.

All of a sudden it came out of nowhere.

We used what little air strikes we had left with helicopters, calling in the strikes on our position to slow it down.

There was no way.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: (explosions) BRADY: What we did was we tried to get out.

Twenty-six of us broke through.

Eleven ultimately made it.

(gunfire) NARRATOR: All that night, the Viet Cong moved among the trees, carrying away their wounded and shooting any South Vietnamese troops they found alive.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: NARRATOR: Cradling his rifle in his arms, Toan began trying to crawl toward Binh Gia.

He was not found for three days.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: NARRATOR: When it was all over, five Americans had died at Binh Gia.

Thirty-two Viet Cong bodies had been left on the battlefield.

200 South Vietnamese were killed; 200 more were wounded.

NGUYEN VAN TONG: BRADY: What it really said was they were capable of marshaling this kind of force.

The Vietnamese officers I talked to in the Marine Corps figured they had six months before the end.

NARRATOR: The big question after Binh Gia, an American officer at headquarters said, is how a thousand or more enemy troops "could wander around the countryside so close to Saigon "without being discovered.

That tells you something about this war."

Hanoi was exultant.

Ho Chi Minh called it "a little Dien Bien Phu."

Le Duan was convinced his strategy was working.

"The liberation war of South Vietnam has progressed by leaps and bounds," he said.

"After the battle of Ap Bac two years ago, "the enemy knew it would be difficult to defeat us.

"After Binh Gia, the enemy realizes that he is in the process of being defeated by us."

NGUYEN VAN TONG: JOHNSON: I, Lyndon Baines Johnson, do solemnly swear... NARRATOR: Twenty-six days after the Binh Gia battle ended and just a week after President Johnson's inauguration, McGeorge Bundy handed the president a memorandum.

I will to the best of my ability.

NARRATOR: The current strategy was clearly not working, it said.

The Viet Cong were on the move and on the rise, supplied and now steadily reinforced with soldiers from North Vietnam.

If an independent South Vietnam was to survive, the United States needed to act fast.

The administration faced two choices, Bundy said.

It could go along as it had been going and try to negotiate some kind of face-saving settlement.

Or they could use still more American military power to force the North to abandon its goal of uniting the country.

Bundy and McNamara favored that option.

Unless the president chose it, they said, South Vietnam would fall.

"I don't think anything," Johnson told McNamara, "is going to be as bad as losing."

Then, a little over a week later, guerrillas struck an American helicopter base at Pleiku in the Central Highlands, killing eight American advisors and wounding over 100 more.

McNAMARA: Approximately 24 hours ago, the first attack in the Pleiku area... NARRATOR: Johnson immediately approved an air strike on a North Vietnamese army barracks.

On February 10, 1965, the Viet Cong blew up a hotel in Qui Nhon, killing 23 Americans and pinning 21 more beneath the rubble.

Johnson ordered another airstrike.

Anxiety about what seemed to be happening spread around the world.

France, which had spent nearly a century in Vietnam, now called for an end to all foreign involvement there.

The British prime minister urged restraint.

Many leaders of the president's own party agreed, though not in public.

In a private memorandum, Johnson's own vice president, Hubert Humphrey, warned him that widening the war would undercut the Great Society, damage America's image overseas, and end any hope of improving relations with the Soviet Union.

Johnson never responded.

Instead, on March 2, 1965, the United States began a systematic bombardment of targets in North Vietnam, code-named Operation Rolling Thunder.

It was meant to be a "mounting crescendo" of air raids, Ambassador Taylor wrote, intended to bolster morale in the South and destroy morale in the North.

WILSON: The thesis behind Rolling Thunder, as I understood it, was that as we ratcheted up the tempo and the volume of this effort against the North Vietnamese, sooner or later they would cry uncle.

And there'd be a pause, and we would begin to negotiate our way out of this situation.

This became an article of faith.

And this article of faith was a fallacious assumption.

They weren't going to give up.

They read us better than we read them.

NARRATOR: The president insisted on strict secrecy-- the American people were not to be told that the administration had changed its policy from retaliatory airstrikes to systematic bombing; that he had, in fact, widened the war.

They jointly agreed that joint retaliatory action was required.

NARRATOR: General Westmoreland, who had initially been hesitant about committing ground troops to Vietnam, now asked for two battalions of Marines-- 3,500 men-- to protect the Danang airbase from which fighter-bombers were hitting the North.

Ambassador Taylor, who had once called for ground troops, now objected to the whole idea.

"Once you put that first soldier ashore," he wrote, "you never know how many others are going to follow him."

But the president felt he had no choice but to give Westmoreland what he asked for.

He knew he would be blamed if more American advisors died.

"I feel like a jackass caught in a Texas hailstorm," he complained.

"I can't run, I can't hide, and I can't make it stop."

("Hello Vietnam" by Johnnie Wright playing) In March of 1965, Johnson finally took the action he had managed to avoid for so long.

WRIGHT: ♪ Kiss me goodbye... ♪ NARRATOR: He was putting American ground troops in Vietnam.

WRIGHT: ♪ Goodbye, my sweetheart; hello, Vietnam ♪ NARRATOR: The government of South Vietnam was not even consulted; the United States of America had larger considerations.

ROBERT GARD: Clearly, we saw it in terms of the Cold War.

Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton said...

He said our interests there were 70% to avoid humiliation, 20% to contain China, and ten percent to help the Vietnamese.

NARRATOR: Johnson quietly told his good friend Senator Richard Russell of Georgia what was about to happen.

JOHNSON: I guess we got no choice, but it scares the death out of me.

I think everybody's going to think, "We're landing the Marines.

We're off to battle."

Of course, if they come up there, they're going to get them in a fight.

And if they ruin those airplanes, everybody is going to give me hell for not securing them, just like they did last time they made a raid.

RUSSELL: Yeah.

JOHNSON: What do you... what do you think?

RUSSELL: Well, Mr. President, it scares the life out of me.

But I don't know how to back up now.

It looks to me like we just got in this thing, and there's no way out.

JOHNSON: I don't know.

Dick, the great trouble I'm under... A man can fight if he can see daylight down the road somewhere.

But there ain't no daylight in Vietnam.

There's not a bit.

NARRATOR: On March 8, 1965, Dr. Phan Huy Quat, yet another prime minister of South Vietnam, called his chief of staff, Bui Diem.

BUI DIEM: NARRATOR: The Marines were landing at Danang on the east coast of South Vietnam, some 100 miles south of the demilitarized zone that divided the North from the South.

They were prepared to fight their way ashore.

They did not need to.

PHILIP CAPUTO: What struck me was how beautiful Vietnam was to look at.

There were just these endless acres of these jade-green rice paddies.

And these lovely villages inside these groves of bamboo and palm trees.

And way off in the distance these bluish jungled mountains, and they looked like Shangri-La.

And I remember seeing this line of Vietnamese women, or schoolgirls I think they were.

They actually looked like angels come to earth or something like that.

So it was really quite striking but a little unsettling because... so how can a place like this-- so beautiful and so enchanting-- be at war?

DUONG VAN MAI: My father was very happy.

We're such a small and poor country and the Americans have decided to come in to save us not only with their money, their resources, but even with their own lives.

We were very grateful.

We thought the... sure enough with this power, the Americans are going to win.

NARRATOR: Seeing foreign troops marching past his village, an old man emerged from his home shouting, "Vivent les Français!"

He thought the French had returned.

"The problem around here," a Marine captain leading a patrol told a reporter, "is who the hell is who?"

WILSON: As a voting member of Saigon Mission Council, I was opposed to the entry of American ground combat forces.

I felt if the Vietnamese had to beat them off with a bloody stump, they had to do it themselves.

We had to do everything we humanly could to help them, but we could not win it for them.

So, I think we crossed the River Styx at that point.

TRAN NGOC TOAN: BILL ZIMMERMAN: The first protest I went to against the war in Vietnam was a protest at a Dow Chemical facility.

Dow was manufacturing napalm.

They were dropping napalm on villages in Vietnam.

It was a very disappointing experience because only 40 people came.

And we seemed very out of place and very ineffectual, impotent, standing outside with 40 people.

NARRATOR: Most Americans understood little about Indochina, rarely knew anyone actually involved in the fighting, saw no reason to question the government's assertion that the United States had vital interests 8,000 miles from home.

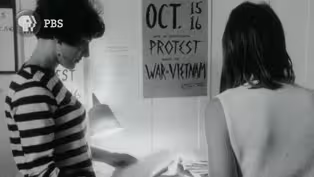

("I Ain't Marching Anymore" by Phil Ochs playing) Still, there was a small but growing number of people who had begun to oppose the war for any number of reasons-- because they thought it unjust or immoral, believed it was unconstitutional or simply not in the national interest.

OCHS: ♪ Oh I marched to the battle of New Orleans ♪ NARRATOR: Two weeks after the Marines landed at Danang, members of the University of Michigan faculty organized a night-long discussion between professors and some 3,000 students about the escalation of the war.

The demonstration was called a teach-in because the idea originated with a group of university professors.

What do you hope to accomplish?

DR. ERIC WOLF: I'd like to open up communication between people and the government because I believe that they are not telling us what is going on, and the people have the right to know, and we have the right to tell the government what we think.

NARRATOR: Soon, there were teach-ins on most major university campuses.

There is no morally wonderful way out.

NARRATOR: NYU in Manhattan, the University of Wisconsin in Madison, the University of California in Berkeley.

The teach-ins were really raucous affairs.

A lot of contention.

STUDENT: We want to discuss is what's wrong with the Vietnam War, and... OCHS: ♪ And so many others ♪ ♪ But I ain't marchin' anymore ♪ REPORTER: Do you endorse the administration's policy in South Vietnam?

Whole-heartedly.

ZIMMERMAN: There were plenty of times when people who were supportive of the war came to these teach-ins to try to give an alternative anticommunist point of view.

They were often shouted down.

(crowd booing) NARRATOR: The bombing of the North and the Marines' arrival also drew protestors to Washington that spring.

The demonstration was organized by the Students for a Democratic Society-- the SDS.

I saw SDS calling for a demonstration at the White House in the spring of 1965.

I didn't want to go because I didn't want to be disappointed in the same way again and, you know, go all the way to Washington and stand outside the White House with 40 people.

(crowd cheering) 25,000 people attended that rally.

And that suddenly told me and others I was working with at the time that it might be possible to build an antiwar movement.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: It was quite astounding to think that he had that degree of commitment.

And it made sense in what we knew of him, as drastic as it was.

("It's My Life" by the Animals playing) NARRATOR: Nothing Mogie Crocker's parents could say or do since Mogie had come home shook his determination to serve, and recent developments in Vietnam had only strengthened his resolve.

He wanted to become a paratrooper and get into combat.

His parents finally, reluctantly, agreed to let him go, and on March 15, a week after the first Marines landed at Danang, Denton Crocker, Jr. entered the United States Army.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: So Denton bounced down the steps one morning and was off to Fort Dix.

It was in a way a sort of relief, actually, that the conflict and the anxiety over whether he would or would not go was done.

And he was happy.

And we just tried to believe that this was the right thing for him to do.

LE MINH KHUE: NARRATOR: Le Minh Khue was orphaned as a small girl, her parents victims of the brutal land reforms the communists had imposed.

She was raised by her aunt and uncle, who encouraged her to read American literature.

She was 16 when Operation Rolling Thunder began.

LE MINH KHUE: NARRATOR: Khue was assigned to an organization called the "Youth Shock Brigades Against the Americans for National Salvation," and along with thousands of other young people was sent south to work keeping open the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

LE MINH KHUE: NARRATOR: As Johnson had feared, it quickly became clear that the bombing campaign alone was not working.

Troops and supplies continued steadily to filter down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

General Westmoreland and the Joint Chiefs called for more men, tens of thousands of them.

The president was cautious.

He wanted to do "enough, but not too much," he said.

But he quietly agreed to send two more Marine battalions and changed their mission from base security to active combat.

For the first time, American troops were being asked to fight on their own in Vietnam.

Johnson did not want that fact revealed to the American public either.

But the bombing of the North and rumors of harsher measures to come had heightened concern around the world.

UN Secretary-General U Thant had proposed a three-month ceasefire.

Great Britain, America's closest ally, publicly offered to reconvene the Geneva Talks that had divided Vietnam in 1954, with the goal of reuniting it.

JOHNSON: The people of South Vietnam be allowed to guide their own country... NARRATOR: On April 7, at Johns Hopkins University, Johnson sought to persuade the world of America's good intentions and again to calm American fears of a wider war.

In recent months, attacks on South Vietnam were stepped up.

Thus, it became necessary for us to increase our response and to make attacks by air.

This is not a change of purpose.

It is a change in what we believe that purpose requires.

NARRATOR: Nothing was said about the new orders sending Marines directly into combat.

Instead, the president called for "unconditional discussions" with Hanoi, and as an old New Dealer, proposed a massive development program for all of Southeast Asia.

JOHNSON: The vast Mekong River can provide food and water and power on a scale to dwarf even our own TVA.

(gunfire) BRADY: I was outside of the village.

We're getting some fire from the village.

I had the little transistor radio.

And I'm sitting there listening to LBJ.

JOHNSON: ...will use our power with restraint and with all the wisdom... At the same time we got to lay some nape on the village.

So I'm calling in the nape and listening to the president talk peace.

JOHNSON: We will try to keep conflict from spreading.

BRADY: It was surreal.

JOHNSON: We have no desire to devastate that which the people of North Vietnam have built with toil and sacrifice.

This war, like most wars, is filled with terrible irony.

What do the people of North Vietnam want?

(sirens wailing) NARRATOR: Hanoi denounced the president's offer as a trick.

Johnson's advisors and the Joint Chiefs of Staff continued to debate how many men would actually be needed and how rapidly they should be deployed.

Meanwhile, the president sent the first Army combat troops to the country.

It was increasingly clear that the United States was in it for the long haul.

You can't just be a neutral witness to something like war.

It crawls down your throat.

It eats you alive from the inside and the out.

It's not something that you can stand back and be neutral and objective and all of those things we try to be as reporters, journalists, photographers.

It doesn't work that way.

MAN (on radio): ...defense and they're real quick... and check it out... NARRATOR: The growing presence of American combat troops in Vietnam attracted flocks of journalists.

There was no press censorship, as there had been in World War II.

Reporters just had to agree to follow military guidelines so as not to compromise the security of ongoing operations.

It was dangerous work.

More than 200 journalists and photographers would die covering the fighting in Southeast Asia.

Joseph Lee Galloway was a young UPI reporter from Refugio, Texas.

He stopped in Saigon just long enough to get his credentials.

Then he headed for Danang.

GALLOWAY: The Marines originally came ashore there to guard the airbase.

And they quickly figured out you can't just guard an airbase.

You've got to spread out because they're going to mortar it, they're going to shoot rockets.

So you've got to reach out 15 or 20 miles.

That means you've got to run operations that far out.

And once you're doing that, you're no longer guarding an airbase... (gunfire) ...you're operating in hostile territory.

(soldiers cheering) NGUYEN THANH SON: CAPUTO: It wasn't so much the Viet Cong that were intimidating at that point as it was the terrain.

Going from Point A to Point B in the jungle was so difficult.

As it happened to me once, it took four hours to move a half a mile, cutting through this bush with machetes.

GALLOWAY: The Viet Cong knew the terrain far better than the Marines did, and ran circles around them.

(gunfire) MOGIE CROCKER (dramatized): Fort Dix, June 10, 1965.

Dear Mum, Basic is now all over and I am presently waiting for orders.

Waiting for orders could be very dull but I have found there are excellent chances to do some reading.

Recently I have read Wuthering Heights, Animal Farm, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, and Lord Jim.

I hope you are all well.

Love, Mogie.

NARRATOR: Mogie Crocker was allowed two weeks at home before shipping out to Vietnam.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: We were at dinner one evening just talking, I guess, in generalities about the war and the general situation.

And Mogie said, "Of course if I were a Vietnamese, I would be on the side of the Viet Cong."

That...

I puzzled over that.

I suppose relating like to our American Revolution that he saw their need for their own freedom.

But as an American citizen, he saw the larger picture of trying to prevent communism.

CAROL CROCKER: I remember one night in particular he and I were up late.

And he suddenly leaned his head in his hands.

And he said, "I don't want to go back."

I was dumbstruck.

And said to him, "But this is what you want to do."

It had never occurred to me that he was torn about this, that he was afraid and yet was determined to go.

("Play With Fire" by the Rolling Stones playing) NARRATOR: In South Vietnam, things were steadily growing worse.

JAGGER: ♪ Well, you've got your diamond.

♪ NARRATOR: In May, the Viet Cong, supported now by four regiments of North Vietnamese regulars-- approximately 5,000 men-- were destroying the equivalent of a South Vietnamese battalion every week.

JAGGER: ♪ But don't play with me ♪ ♪ Because you're playing with fire.

♪ NARRATOR: South Vietnam now seemed only weeks from complete collapse.

Desperate, General Westmoreland requested tens of thousands of more American troops right away.

But neither the continuing bombing nor the growing likelihood of full-scale American intervention seemed to intimidate Hanoi.

Le Duan, having failed to win the war before the United States sent in ground troops, was now persuaded the American public, like the French public before them, would eventually weary of a costly, bloody war being waged so far from home.

By contrast, he said, "The North will not count the cost."

Le Duan's confidence was bolstered by the help American intervention had forced the Soviet Union and China to offer him.

Moscow agreed to supply vast amounts of modern weaponry and materiel.

Hanoi would eventually become the most heavily defended city on Earth.

And China agreed to send support troops, freeing North Vietnamese soldiers for combat in the South.

320,000 Chinese would eventually serve behind the lines in the North.

"We will fight," Le Duan promised, "whatever way the United States wants."

JOHN NEGROPONTE: In June of 1965, Secretary McNamara, the Secretary of Defense, came out to Saigon.

There were a lot of captains and majors and lieutenants.

And every person said to Mr. McNamara, "The situation is so dire we must bring in United States forces."

So, whatever doubts we may have had, whatever people may say after the fact, I recall distinctly at the time telling the Secretary of Defense that I thought we needed to bring troops in there.

NARRATOR: For three weeks, the president and his advisors argued over how to respond to Westmoreland's urgent request for more troops, differing mostly over how many should be sent how fast.

Undersecretary of State George Ball made the argument against further escalation.

He told the president the war could not be won.

The American people will grow weary of it.

Our troops will get bogged down "in the jungles and rice paddies," he warned, "while we slowly blow the country to pieces."

No one else agreed.

JAGGER: ♪ But don't play with me... ♪ NARRATOR: In the end, Johnson sent Westmoreland 50,000 men.

But he pledged another 50,000 by the end of 1965, and still more if they were needed.

JAGGER: ♪ Because you're playing with fire.

♪ SOLDIERS: ♪ Gory, gory, what a hell of a way to die ♪ TRAN NGOC TOAN: MAN: Hold your fire!

Hold your fire.

JOHN SCALI: Does the fact that you are sending additional forces to Vietnam imply any change in the existing policy of using American forces to guard American installations and to act as an emergency backup?

It does not imply any change in policy whatever.

It does not imply any change of objective.

Uh... LOU CIOFFI: The month of June saw soldiers here taking what appears to be... NARRATOR: Most television reports from Vietnam echoed the newsreels Americans had flocked to see during the Second World War-- enthusiastic, unquestioning, good guys fighting and defeating bad guys.

But at dinnertime on August 5, 1965, Americans saw another side of the war.

MORLEY SAFER: We're on the outskirts of the village of Cam Ne with elements of the 1st Battalion... NARRATOR: CBS correspondent Morley Safer and his crew went on patrol with Marines near Danang.

Their orders were first to search a cluster of four villages for caches of arms and rice meant for the enemy and then to destroy them all.

This is what the war in Vietnam is all about.

(speaking Vietnamese) The old and the very young.

The Marines have burned this old couple's cottage because fire was coming from here.

And now when you walk into the village you see no young people at all.

(woman speaking Vietnamese) The day's operation burned down 150 houses, wounded three women, killed one baby, wounded one Marine, and netted these four prisoners.

Today's operation is the frustration of Vietnam in miniature.

There is little doubt that American firepower can win a military victory here.

But to a Vietnamese peasant whose home is a... means a lifetime of backbreaking labor, it will take more than presidential promises to convince him that we are on his side.

NARRATOR: The next morning, the president called his friend Frank Stanton, the head of CBS.

"Hello, Frank, this is your president.

Are you trying to ...

me?"

Safer had defaced the American flag, Johnson said.

He was probably an agent of the Kremlin, had to be fired.

The Marines claimed Safer had provided a zippo lighter and asked the Marines to burn the hut for the camera.

A major at the Danang Marine press office called CBS the "Communist Broadcasting System."

But after the operation, Safer interviewed some of the Marines who'd burned Cam Ne.

Do you ever have any private thoughts, any private regrets about some of these people you are leaving homeless?

I feel no remorse.

I don't imagine anybody else does.

You can't expect to do your job and feel pity for these people.

NARRATOR: When some viewers registered their shock, Westmoreland admitted, "We have a genuine problem "which will be with us as long as we are in Vietnam.

"Commanders must exercise restraint unnatural to war and judgment not often required of young men."

CAPUTO: You kind of thought at first that it was going to be like the GIs, you know, rolling through Paris after the liberation.

Well, you know, it sure didn't work out that way.

I can remember once going in this one ville.

And I remember finding this entire Vietnamese family cowering in a bunker.

And they were terrified of us.

And I remember thinking to myself, I said, "Well, I wonder if back in the colonial days, "when the Redcoats barged into Ipswich, Massachusetts, "or wherever, "if this is how Americans must have felt looking at these foreign soldiers coming in here."

FREDERICK ACKERSON: The Viet Cong have terrorized you, and have burned your homes.

We are here to help you.

To show how much we are able to protect you, we are going to have the Air Force hit some Viet Cong on the other side of the valley.

That will be at 10:30.

(playing "Colonel Bogey" march) (distant explosion) MOGIE CROCKER (dramatized): Dear Mum and Dad, I am now with the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division in Vietnam.

("The War Drags On" by Donovan playing) What is taking place in America?

We who are in Vietnam find these protests very hard to comprehend, and many people here are quite bitter about them.

DONOVAN: ♪ Let me tell you the story in South Vietnam.

♪ MOGIE CROCKER (dramatized): The belief I have in our present policy has been completely confirmed by what I have seen here.

My chief worry is that these pacifist bleatings might effect even a small change in government policy at a time when we appear close to success.

DONOVAN: ♪ And the war drags on.

♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: As Vietnam began to be more and more chaotic, I certainly wondered very much whether we should be there.

But I never expressed that to him.

That's one of those conflicts that's just too difficult to bring up, or at least it was for me.

("Big River" by Johnny Cash playing) CASH: ♪ Now I taught the weeping willow how to cry ♪ ♪ And I showed the clouds how to cover up a clear blue sky.

♪ GALLOWAY: We were all excited about the arrival of the 1st Cavalry Division, an experimental unit.

They've been trained in air-mobile warfare using these helicopters to the absolute maximum benefit.

They're moving their artillery by helicopter, jumping it, leapfrogging troops, chasing the enemy, driving him crazy.

This is something new, and it's going to change the way we do war.

CASH: ♪ I found her trail in Memphis... ♪ NARRATOR: In September of 1965, the newly created 1st Cavalry Division-- 16,000 men, 1,600 vehicles, 435 helicopters-- had begun arriving at An Khe, a massive base carved out of the grasslands at the edge of the Central Highlands.

Its heliport would come to be called the "Golf Course."

As the 1st Cavalry got used to its new surroundings, thousands of North Vietnamese regulars were slipping south into the Highlands along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, joining Viet Cong units already in place.

They established their own base on and around a jumble of thickly forested mountains and ravines south of the Ia Drang River.

On the evening of October 19, communist commandos slipped to within 40 yards of the perimeter wire of the U.S. Special Forces outpost at Plei Me, which was defended by a 12-man team of U.S. Green Berets, 14 ARVN, and some 400 mountain tribesmen.

Nine of the 12 Green Berets were hit.

They managed to hold out for two days before 15 more Green Berets and 160 South Vietnamese Rangers were helicoptered in, commanded by Major Charles Beckwith, known to his fellow soldiers as Chargin' Charlie.

(explosion) The next day, Joe Galloway managed to talk a helicopter pilot into flying him into the besieged camp.

GALLOWAY: That's where I met Major Charles Beckwith.

He said, "I need everything in the world.

"And what has the Army in its wisdom sent me but a godforsaken reporter?"

He drug me over and showed me a 30-caliber air-cooled machine gun.

He showed me how to load it, how to clear a jam.

NARRATOR: "You can shoot the little brown men outside the wire," Beckwith told Galloway.

"You may not shoot the little brown men inside the wire; they are mine."

GALLOWAY: And I'm sitting there thinking, "Ah, I'm a civilian noncombatant."

I tried that line on Beckwith and he said, "Ain't no such thing in these mountains, son."

NARRATOR: For nearly a week, the North Vietnamese launched assault after assault on Plei Me.

It was only after American bombs and napalm turned the surrounding terrain into a moonscape that the enemy withdrew.

JOHN LAURENCE: What kind of fighters are the Viet Cong that you met here?

I would give anything to have 200 of them under my command.

They're the finest soldiers I've ever seen.

The Viet Cong.

That's right.

They're dedicated, and they're good soldiers.

They're the best I've ever seen.

NARRATOR: Despite the losses his men had suffered at Plei Me, the North Vietnamese commander, General Chu Huy Man, was eager for another confrontation with the Americans.

He was determined to learn how to fight them.

Reinforcements streaming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the Ia Drang Valley included a newly minted second lieutenant, Lo Khac Tam, who had volunteered to fight in the South.

NARRATOR: On the morning of November 14, 1965, 1st Cavalry helicopters belonging to the 1st Battalion of the 7th Regiment-- George Armstrong Custer's old outfit-- flew west along the Ia Drang toward the Chu Pong Massif, looking for the enemy.

Their commander, Kentucky-born Korean-War veteran Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore, had been told there was a large enemy base camp somewhere on its slopes.

His orders were to take his understrength outfit-- 29 officers and just 411 men-- find the enemy and kill him.

There were two clearings large enough for Moore to bring in eight choppers at once.

He chose the one closest to the mountain-- Landing Zone X-Ray.

Moore made a point of leading from the front.

He was the first man off the first chopper.

He sent four six-man squads 100 yards in every direction.

The Ia Drang Valley was so beautiful, one soldier remembered, it reminded him of a national park back home.

Within minutes, Moore's men captured a deserter.

Terrified and trembling, he said there were three battalions of soldiers on the mountain-- 1,600 men.

They wanted very much to kill Americans, he said, but so far had been unable to find any.

Moore quickly set up a command post behind one of the huge termite mounds that dotted the clearing.

It would take until mid-afternoon for all of his men to be ferried in.

He had no time to waste.

"We needed to get off the landing zone and get at them before they could hit us," Moore remembered.

He sent two companies up the slope toward the hidden enemy.

Most of the North Vietnamese, like the Americans, were new to combat.

They were ordered to fix bayonets.

LO KHAC TAM: NARRATOR: Colonel Moore had no way of knowing that instead of 1,600 enemy soldiers on the mountain, there were 3,000-- seven times his strength.

(gunfire) Within minutes, the Americans found themselves under attack from hundreds of North Vietnamese soldiers.

In the fighting, an overeager second lieutenant led his platoon of 28 men too far away from the rest of his company and was surrounded.

(gunfire, shouting) The lieutenant was killed.

The sergeant who took his place was shot through the head.

By late afternoon, only seven of the trapped platoon's men were still capable of firing back.

(gunfire, shouting) Moore was now engaged in three simultaneous struggles-- to defend the landing zone, attack the North Vietnamese, and find a way to rescue his trapped patrol.

That night, Joe Galloway again managed to talk his way onto a chopper taking ammunition and water to the besieged Americans.

As the helicopter approached the battlefield, Galloway was sitting on a crate of grenades, peering out into the darkness.

GALLOWAY: And I could see these little pin pricks of light coming down the mountain.

This was the enemy approaching for the next day's attacks.

We flew in there.

As they pulled on out, it was dead dark.

And we're lying there waiting for someone to come tell us what to do.

And the next morning, all of a sudden the bottom fell out.

(gunfire) There was an explosion of fire.

The noise is horrendous, unimaginable.

(rapid gunfire, followed by short bursts) (gunfire, shouting) And in the middle of all of this, you know, I-I just flattened out on the ground because all that was being fired seemed to be about two, two-and-a-half feet off the ground.

(gunfire, whistling) NARRATOR: Hundreds of enemy soldiers hurled themselves at the Americans.

They wore webbed helmets camouflaged with grass, and as they came, blowing whistles, screaming, they looked like "little trees," one American remembered.

They were trying to overrun us.

And they came close.

They came close.

(gunfire, shouting) But we had two things going for us.

We had a great commander and great soldiers.

And we had air and artillery support out the yin-yang.

We had it, and they didn't.

NARRATOR: But using that air and artillery support could be dangerous.

Each of Moore's units carefully marked its position with smoke to keep from being mistaken for the enemy by American airmen overhead.

LO KHAC TAM: NARRATOR: Some 18,000 artillery shells would be called in over the course of the battle, some of them landing just 25 yards from Moore's own men.

Helicopter gunships fired 3,000 rockets into the enemy.

The forward air controller called for every available aircraft in South Vietnam to come and help.

Warplanes, including B-52 long-range strategic bombers, were stacked at 1,000-foot intervals above the battlefield, from 7,000 to 35,000 feet, impatiently awaiting targets to strafe or bomb or burn.

"By God," Moore said, "they sent us over here to kill communists and that's what we're doing."

I looked up... and there were two jets aiming directly at our command post.

He's dropped two cans of napalm and it's coming toward us, loblolly, end over end.

And these kids, two or three of 'em, plus a sergeant, had dug a hole or two over on the edge.

And I looked as the thing exploded... And two of them were dancing in that fire.

And there's a rush, a roar, from the air that's being consumed and drawn in as this-this hell come to earth is burning there.

And as that dies back a little, then you can hear the screams.

And someone yells, "Get this man's feet."

And I reach down and the boots crumble, and the flesh is cooked off of his ankles.

And I feel those bones in the palms of my hands.

I can feel it now.

He died two days later.

A kid named Jim Nakayama out of Rigby, Idaho.

NARRATOR: By 10:00 that morning, American airpower had beaten back the enemy assault.

The survivors from the trapped platoon were rescued that afternoon.

They had been pinned to the ground and under fire for so long that they had to be coaxed into getting to their feet again.

On the morning of the next day, enemy soldiers hurled themselves against the same sector of Moore's line four more times and were obliterated by artillery and machine gun fire.

The surviving North Vietnamese and Viet Cong withdrew into the forest, leaving behind a ghastly ring of their dead surrounding the landing zone-- 634 corpses, shot, blasted, blackened by fire.

LO KHAC TAM: NARRATOR: After three days and two nights of combat, helicopters began lifting out the American survivors and gathering up the dead.

SOLDIER: When you look at them, it doesn't even resemble a human body.

It just, it looks just like a mannequin.

You look at them and say, "That couldn't happen to me."

SHEEHAN: I saw them fight at Ia Drang.

It always galls me when I read or hear about the World War II generation as the greatest generation.

These kids were just as gallant and as courageous as anybody who fought in World War II.

NARRATOR: Seventy-nine of Hal Moore's men lost their lives at Landing Zone X-Ray in the Ia Drang Valley and another 121 were wounded.

Please convey to the American people what a tremendous fighting man we have here.

He's courageous, he's aggressive, and he's kind.

And he'll go where you tell him to go.

And he's got self-discipline.

And he's got good unit discipline.

He's just an outstanding man.

And... Having commanded this battalion for 18 months... You must excuse my emotion here, but when I see some of these men go out the way they have...

I haven't...

I can't tell you how highly I feel for them.

They're tremendous.

NARRATOR: Hal Moore refused to leave until every single man in his command had been accounted for.

He had been the first of his men to step onto Landing Zone X-Ray, and he made sure he was the last to leave it.

LO KHAC TAM: NARRATOR: The North Vietnamese suffered terrible losses in the Ia Drang Valley and many of the survivors were traumatized.

"The units were enveloped in an atmosphere of gloom," a North Vietnamese colonel remembered.

Some men would not leave their rope hammocks.

Some refused to wash. One soldier wrote a poem expressive of their plight: "The crab lies still on the chopping block Never knowing when the knife will fall."

GALLOWAY: In the Ia Drang we killed ten of them for every one of us.

That's a ten-to-one kill ratio is how the military puts that.

But the enemy, he was fully prepared to pay that price and more for the value of the lessons he learned.

LO KHAC TAM: JOE GALLOWAY: Grab 'em by the belt buckle.

That means you've got to get so close, they can't use the artillery and the aerial bombardments on you for fear of killing their own.

Get in so close that it's man-on-man.

And then everything is even.

The Vietnamese suffered hundreds of dead attacking Hal Moore's battalion at LZ X-Ray.

But then they ambushed another battalion a couple of days later and wiped it out.

NARRATOR: In the fighting near Landing Zone Albany, the enemy had gotten too close for artillery to be called in.

Out of some 425 Americans involved, 155 were killed.

124 more were wounded.

Both sides claimed victory in the Ia Drang Valley.

The Americans talked up the number of enemy dead at Landing Zone X-Ray.

The ratio of losses to your kill... NARRATOR: The North Vietnamese took their lessons from Landing Zone Albany.

WILLIAM WESTMORELAND: I don't anticipate that this conflict will end any time soon, and we could find that we have more difficult days ahead.

Certainly we must be prepared for this.

EHRHART: In the fall of my senior year, November 1965, was that huge battle at the Ia Drang Valley, which was the first time there was actually confirmed North Vietnamese regular soldiers as opposed to Viet Cong.

And of course my way of interpreting that was, "There it is, that's the proof.

The North Vietnamese are the aggressors here."

And that's when I began thinking in terms of maybe I don't want to go to college right away.

Maybe I'll join the Marines.

And it was always the Marines.

I never... there was no question.

The Marine Corps is full of little guys like me with chips on our shoulder.

("Eve of Destruction by Barry McGuire plays) McGUIRE: ♪ The eastern world, it is explodin'.

♪ NARRATOR: The battles in the Ia Drang Valley may have been declared American victories, but privately, General Westmoreland and the Johnson administration were worried.

In spite of the Americans' new airborne mobility, the enemy had been able to choose the place and time of battle.

The intelligence on which basic decisions had been made in Washington had been uniformly bad.

There were now believed to be 12 Viet Cong regiments in South Vietnam, not just five; nine North Vietnamese regiments, not three.

Despite months of bombing, three times as many North Vietnamese regulars were now slipping south of the demilitarized zone as originally believed.

Hanoi seemed to be escalating, too.

And American casualties were climbing.

When Senator Fritz Hollings visited Saigon shortly after the Ia Drang battles, General Westmoreland told him, "We're killing these people at a rate of ten to one."

Hollings warned him, "Westy, the American people don't care about the ten.

They care about the one."

Westmoreland, who had said he could win the war in three years, now sent an urgent cable to Washington asking for 200,000 more troops.

McGUIRE: ♪ Yeah, my blood's so mad... ♪ NARRATOR: "The message came as a shattering blow," Robert McNamara remembered.

Once again, he offered Johnson two options: try to negotiate a compromise with Hanoi, or accede to Westmoreland's request for more men, though the chances of victory, the secretary of defense said, might be no better than one in three.

GALLOWAY: And then they all sat down and voted for option two.

McGUIRE: ♪ Over and over and over... ♪ KARL MARLANTES: My bitterness about the political powers at the time was, first of all, the lying.

I mean, I can understand a policy error that is incredibly, incredibly painful and kills a lot of people out of a mistake if they made that with noble hearts.

That was, you know, when Eisenhower and Kennedy were trying to figure things out.

And you read that, you know, McNamara knew by '65-- it was just three years before I was there-- that the war was unwinnable.

That's what makes me mad.

Making a mistake, people can do that.

But covering up mistakes, then you're killing people for your own ego.

And that makes me mad.

NARRATOR: Tens of thousands of American troops continued to prepare to deploy to Vietnam from all over the country, and General Westmoreland and his commanders drew up plans for major offensives in the new year of 1966.

Meanwhile, hoping the Soviets might help bring Hanoi to the bargaining table, McNamara urged the president to declare a halt to the bombing of North Vietnam.

Over the objections of the military, who worried it would give the enemy time to rebuild its defenses, Johnson agreed to stop the bombing on Christmas Eve.

If it achieved nothing else, he said, it would show the American people that before he committed more of their sons to battle, "We have gone the last mile."

("Little Drummer Boy" by Burl Ives playing) JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: Well, Christmas always meant a great deal in our family.

We sent packages to Denton, of course.

Then a neighbor mentioned to me that she heard a local television station was offering free tapes to be made to send to a soldier overseas.